Abstract and Introduction

Introduction

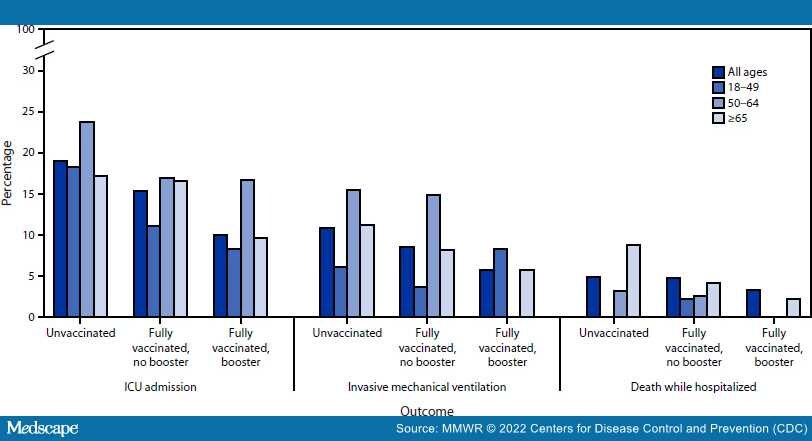

In mid-December 2021, the B.1.1.529 (Omicron) variant of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, surpassed the B.1.617.2 (Delta) variant as the predominant strain in California.§ Initial reports suggest that the Omicron variant is more transmissible and resistant to vaccine neutralization but causes less severe illness compared with previous variants.[1–3] To describe characteristics of patients hospitalized with SARS-CoV-2 infection during periods of Delta and Omicron predominance, clinical characteristics and outcomes were retrospectively abstracted from the electronic health records (EHRs) of adults aged ≥18 years with positive reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) SARS-CoV-2 test results admitted to one academic hospital in Los Angeles, California, during July 15–September 23, 2021 (Delta predominant period, 339 patients) and December 21, 2021–January 27, 2022 (Omicron predominant period, 737 patients). Compared with patients during the period of Delta predominance, a higher proportion of adults admitted during Omicron predominance had received the final dose in a primary COVID-19 vaccination series (were fully vaccinated) (39.6% versus 25.1%), and fewer received COVID-19–directed therapies. Although fewer required intensive care unit (ICU) admission and invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV), and fewer died while hospitalized during Omicron predominance, there were no significant differences in ICU admission or IMV when stratified by vaccination status. Fewer fully vaccinated Omicron-period patients died while hospitalized (3.4%), compared with Delta-period patients (10.6%). Among Omicron-period patients, vaccination was associated with lower likelihood of ICU admission, and among adults aged ≥65 years, lower likelihood of death while hospitalized. Likelihood of ICU admission and death were lowest among adults who had received a booster dose. Among the first 131 Omicron-period hospitalizations, 19.8% of patients were clinically assessed as admitted for non–COVID-19 conditions. Compared with adults considered likely to have been admitted because of COVID-19, these patients were younger (median age = 38 versus 67 years) and more likely to have received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine (84.6% versus 61.0%). Although 20% of SARS-CoV-2–associated hospitalizations during the period of Omicron predominance might be driven by non–COVID-19 conditions, large numbers of hospitalizations place a strain on health systems. Vaccination, including a booster dose for those who are fully vaccinated, remains critical to minimizing risk for severe health outcomes among adults with SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Periods of Delta and Omicron predominance (July 15–September 23, 2021, and December 21, 2021–January 27, 2022, respectively) were defined to correspond to peaks in SARS-CoV-2 hospitalizations during which each variant accounted for ≥50% of sequenced SARS-CoV-2 isolates in California (Supplementary Figure, https://stacks. cdc