Editor's Note: The audio quality of the interview is variable, so a complete written transcript is provided below. In 2002, forensic pathologist Bennet Omalu, MD, MBA, MPH, made a remarkable discovery that has changed the face of football and other high-impact sports. After performing the autopsy and a microscopic examination of the brain of Pittsburgh Steelers center Mike Webster, who died of a heart attack, Dr Omalu published the first ever reported case of the condition he named "chronic traumatic encephalopathy" (CTE) in a football player.[1] Professional football failed to accept Dr Omalu's findings graciously, and, under attack every step of the way, Dr Omalu embarked on a long journey to repair his reputation and convince the medical community of the validity of his findings. This journey was originally documented in a book (Concussion, by Jeanne Marie Laskas) and subsequently made into a film of the same name. Medscape Editor-in-Chief Eric J. Topol, MD, recently spoke with Dr Omalu, who told the fascinating story of the discovery of CTE.

A Feeling That Something Was Wrong

Dr Topol: Hello. This is Eric Topol for Medscape and I’m truly delighted today to welcome Dr. Bennet Omalu, who is a pathologist presently living in California.

Dr Omalu is the subject of a phenomenal book called Concussion and is also played by Will Smith in the movie of the same name. Dr Omalu has played an extraordinary role in uncovering the importance of head trauma in football, and is one of the most interesting people in medicine. Welcome—it's wonderful to have you with us at Medscape.

Bennet Omalu, MD, MBA, MPH: Thank you for having me.

Dr Topol: In 2002, when you had the brain tissue of noted Pittsburgh Steelers player Mike Webster, you postponed doing the microscopic exam. You waited a while. Why didn't you want to get into it right away?

Dr Omalu: If you have read the story, you will remember that I had no reason to do an autopsy on Mike Webster (Figure).

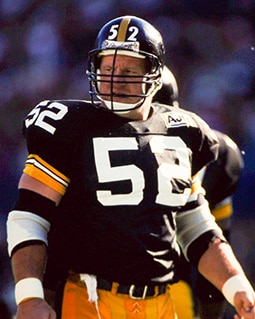

Figure. Pittsburgh Steelers center Mike Webster, who died of a myocardial infarction in 2002.

We knew why he died—he had a massive heart attack. At autopsy, his brain appeared grossly normal. I had no reason to even save his brain, but I did. The office had refused to pay for the analysis, rightfully, because there was no need for me to examine the brain. Lucky for me, I had a very intellectually inclined boss, Cyril Wecht, who allowed me to proceed. He asked if I knew what I was looking for, and I said, "I don't know." I just had an intuition that something was wrong—something just didn't match. Like everyone else, he was afraid of what I was going to see, but I was afraid that I wouldn't see anything at all. That would have been very disappointing. It would have meant that everything I knew—all my years of education studying the brain—would have come to naught. I couldn't help Mike Webster like I promised I would.

Afraid to Look Under the Microscope

Dr Topol: Bennet, what was it like, looking under the microscope at the brain slides for the first time? Can you recreate that moment?

Dr Omalu: The technician had told me that the slides were ready. I picked them up, but I did not look at them—that was how afraid I was. I took the slides home with me to spend time with them. I had a microscope at home, and I spent hours just looking at the slides. I spent hours and hours just to figure out the tauopathy I was seeing, and the amyloidopathy. I was trying to document it extensively. I was puzzled—I did not understand what I was seeing. I became even more confused. Using the guidelines of the American Society for Clinical Pathology, when you see something distinctive, you show it to another pathologist. I took the slides to my former professor, Ronald Hamilton. He looked at them and said, "Bennet, why are you showing me an old person's brain?" I said, "This is not an old person. This is Mike Webster. He was 50 years old." I got his attention. He looked at the slides and said, "This is not Alzheimer's." I said, "That's why I'm showing it to you."

It didn't match up with dementia pugilistica. Mike Webster wasn't a boxer. Dr Hamilton suggested showing the slides to Steven DeKosky, a well-established Alzheimer disease neurologist. I was afraid that Dr DeKosky would dismiss my finding, saying that it was nothing or some known disease. I was extremely nervous. Dr DeKosky was a well-established physician, and I was just a young physician who had just finished his fellowship 3 months earlier. I was honored and grateful that he would even talk to me. I thought I would go to his office, spend 5 minutes, and leave. I ended up spending 2 hours. He looked at the slides and confirmed that it wasn't Alzheimer disease or dementia pugilistica. The next question was, "What is it?"

The Disease With No Name

Dr Omalu: I decided that I had to give the condition a name, describe the pathology, and explain why I thought it was a new disease. We knew about dementia pugilistica in boxers, but we weren't aware of any other contact sport with an associated pathology. So, I went back to the literature, back to the time of Hippocrates, who was the one who named commotio cerebri. In my research, I found many descriptive terminologies, but nobody had packaged these terminologies, given the disease a name, and described the pathology. I couldn't believe that there was not a single reported case describing the disease in a football player or other high-impact contact sport outside of boxing.

Even for boxing, the literature believed that the pathology of boxers was a primary amyloidopathy, but I chose to disagree. I believed it was a primary tauopathy and not amyloidopathy. Based on the distinctive findings, I believed that we should not focusing on tau, rather than amyloid.

Blindsided by the NFL

Dr Topol: It took a few years before you published the case report, which, by the way, I reviewed. It's an extraordinary case report, published in Neurosurgery in 2005.[1] It was interesting that you checked to see whether Mike Webster had ApoE4 (he did not). You finally published, with faculty members at the University of Pittsburgh, the paper describing the first case of CTE. Did you know that the National Football League (NFL) was going to activate and try to destroy you at that point?

Dr Omalu: No. I had no idea when I was putting this paper together (which, by the way, took so many years because of the very extensive peer review process.)

Dr Topol: The book, Concussion, points out that the editor of the journal was also a consultant for the NFL. They didn't really want to publish your paper, and when they did, the NFL demanded that it be retracted, which is incredible.

Dr Omalu: That is true. In fact, the reason why I submitted the paper to Neurosurgery was that the NFL was publishing all of its papers in that journal. I thought that my findings were good, that they had propositional value that would enhance the game and the lives of the players. As a physician, I do not see the football players as football players. I see them as human beings and patients.

When I got the phone call from the sports section editor of the journal telling me about the letter asking for retraction, I was extremely disappointed. The NFL made a calculated attempt to exterminate me. They requested that my paper be retracted. Eric, you know what it is for your paper to be retracted. You're finished.

When I saw the adverse response, I started researching the NFL because I had no clue what the NFL was before this. I had no clue about American football. I even got on eBay and bought some very old NFL documents and books. I was traveling across the country, spending my own money to meet the families of these players. I wanted to understand this disease—the constellation of symptoms. I was seeing a commonality in the patterns of presentation. I couldn't believe that nobody knew about this. These players were suffering in silence and in obscurity. I couldn't believe it was happening in America. I began to unravel a systematic and systemic corruption.

As a pathologist, what I do on a daily basis is to use scientific methodology to unravel the truth upon which we base diagnoses. I chose to use my knowledge and my expertise to become the voice of the voiceless, of these players and their families who were suffering in obscurity.

Come Forth and Speak

Dr Topol: Your name, Omalu, stands for, "if you know, come forth and speak." Talk about fate! That's unbelievable.

Dr Omalu: Yes. That's my Nigerian Igbo name. I'm from the Igbo tribe in Nigeria. It is my forefather's name. "If you know, come forth and speak."

Dr Topol: They had public hearings and summit meetings. You discovered this disease, and yet you were never invited to testify.

Medscape © 2015 WebMD, LLC

Any views expressed above are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the views of WebMD or Medscape.

Cite this: “Concussion” Movie's Dr Omalu Tackles NFL on CTE - Medscape - Dec 24, 2015.