Medscape Ethics Report 2014, Part 2: Money, Romance, and Patients

Leslie Kane, MA

December 22, 2014

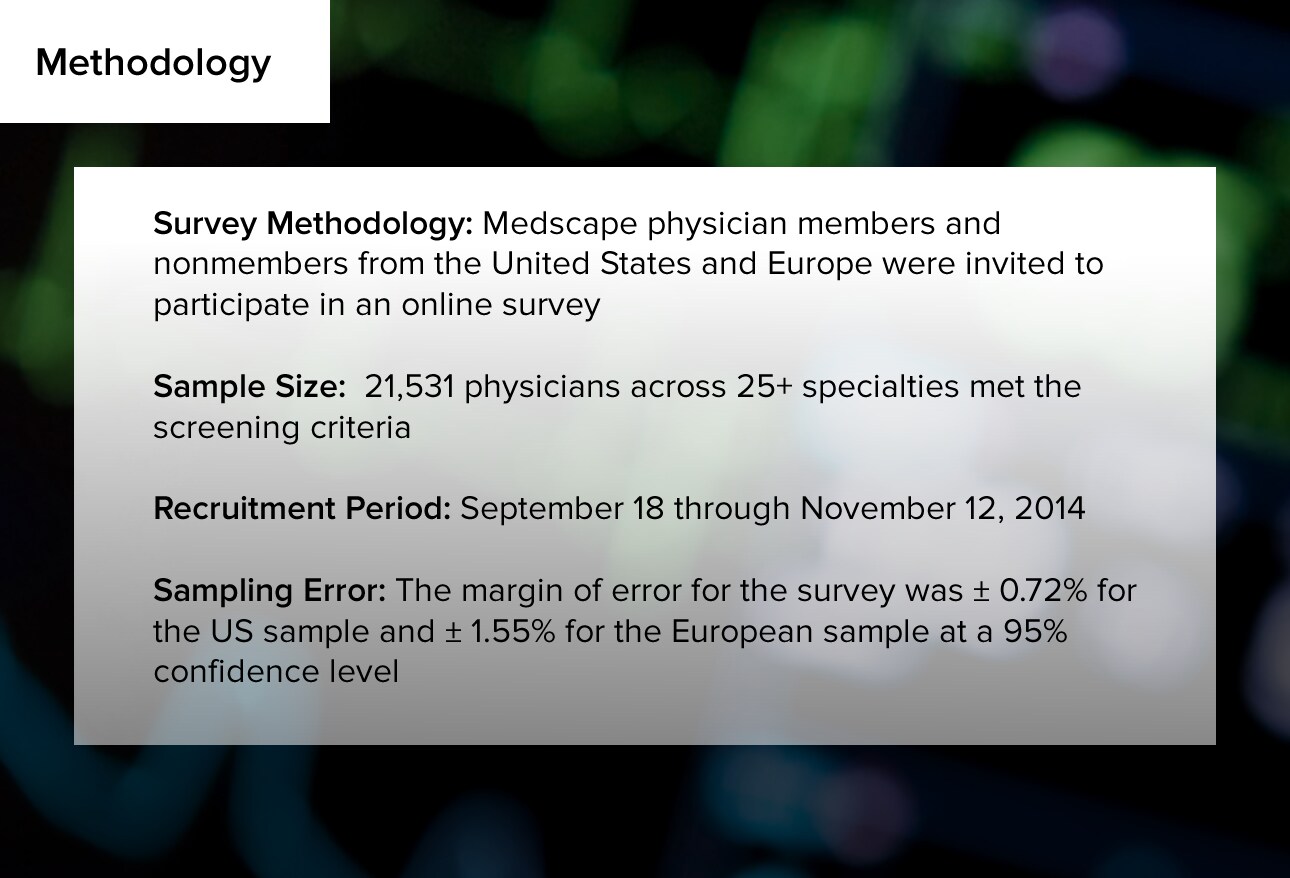

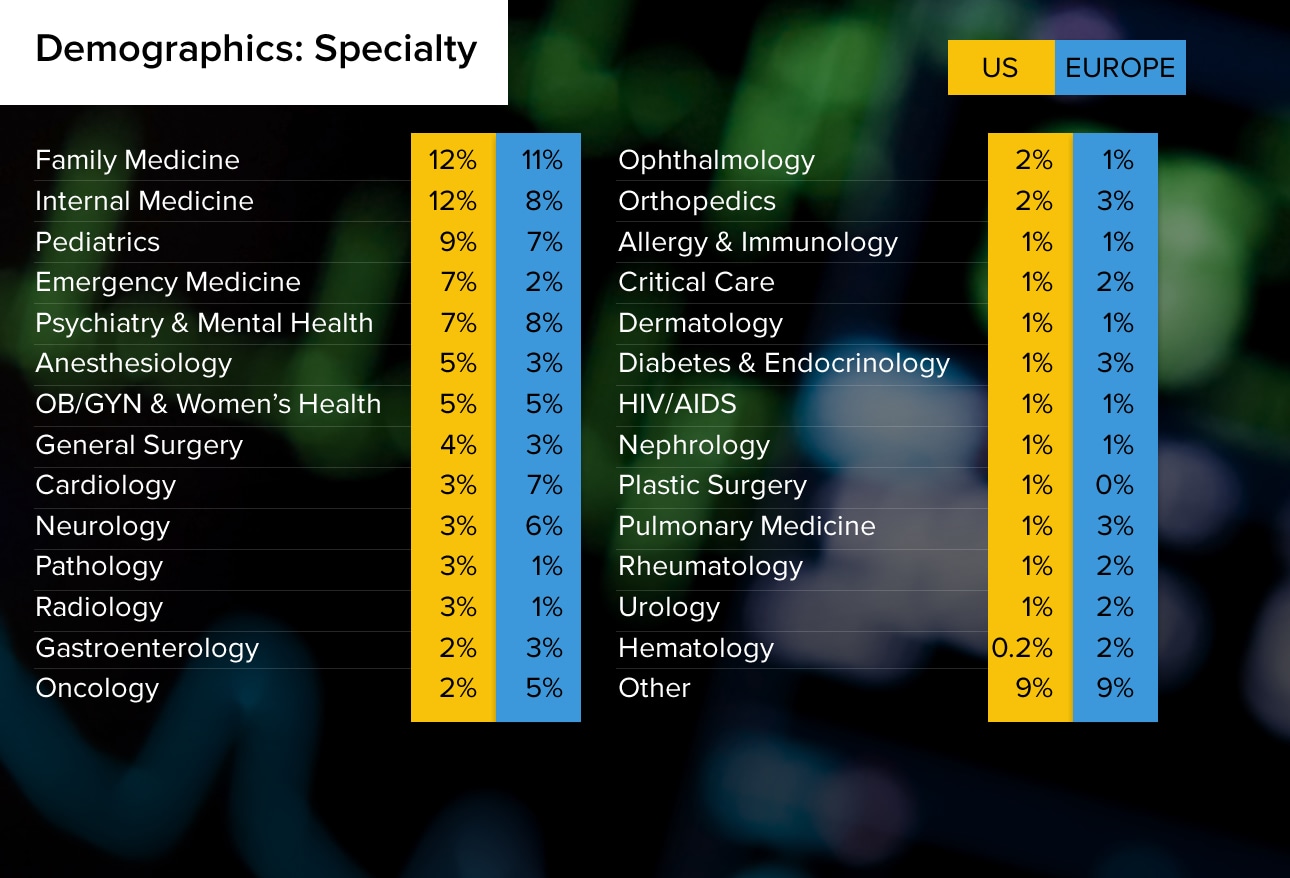

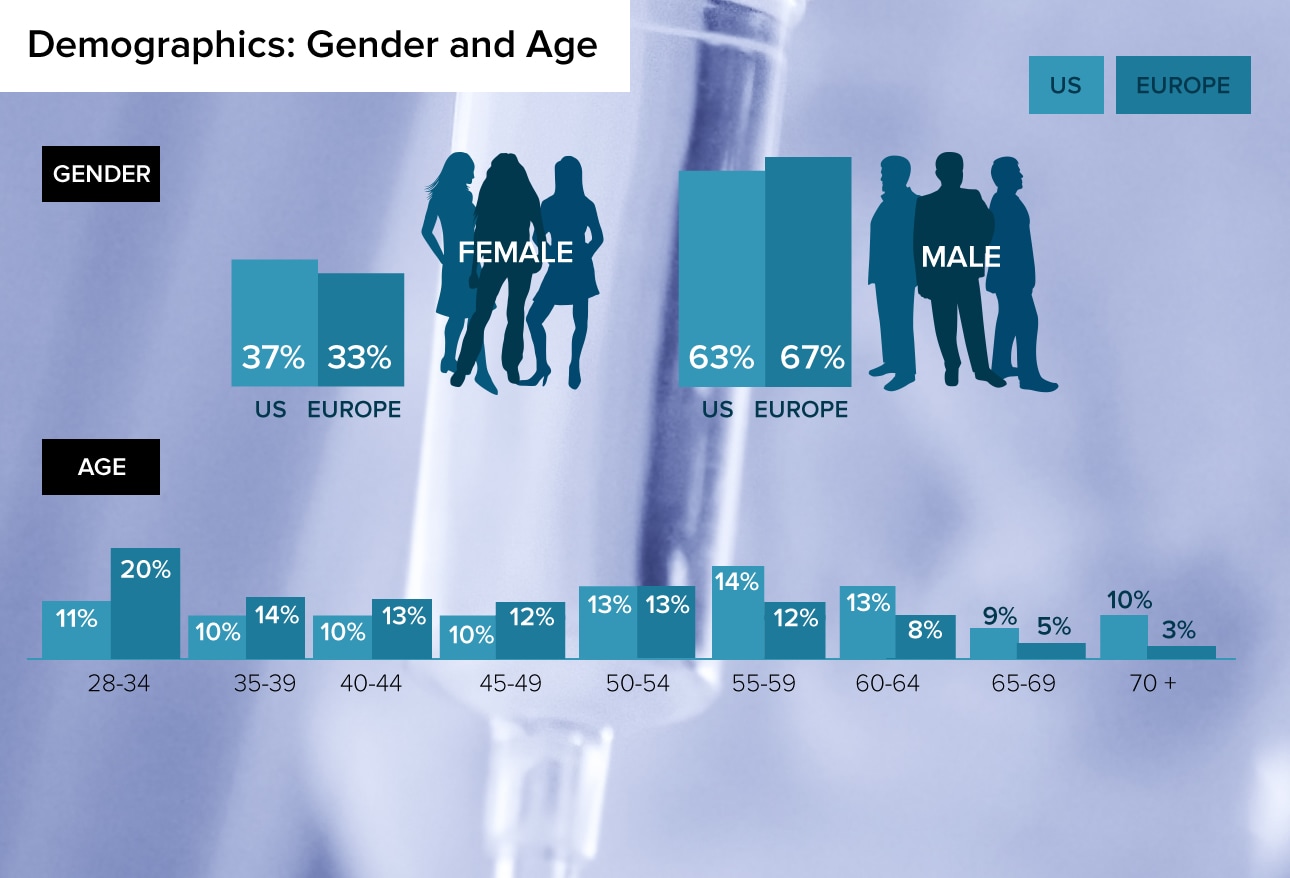

Ethical dilemmas involving money, patients, and romance arise regularly throughout a physician's career. The way physicians choose to deal with them reflects each doctor's individual values and personality, which sometimes may be at odds with the rigorous standards of the profession. More than 21,000 physicians told Medscape how they feel about medicine's most critical issues, including more than 17,000 US physicians and almost 4000 European physicians. This slideshow reports the US physicians' results. Representative respondent comments are also shown, to shed more light on the issues at hand.

Ethical dilemmas involving money, patients, and romance arise regularly throughout a physician's career. The way physicians choose to deal with them reflects each doctor's individual values and personality, which sometimes may be at odds with the rigorous standards of the profession. More than 21,000 physicians told Medscape how they feel about medicine's most critical issues, including more than 17,000 US physicians and almost 4000 European physicians. This slideshow reports the US physicians' results. Representative respondent comments are also shown, to shed more light on the issues at hand.

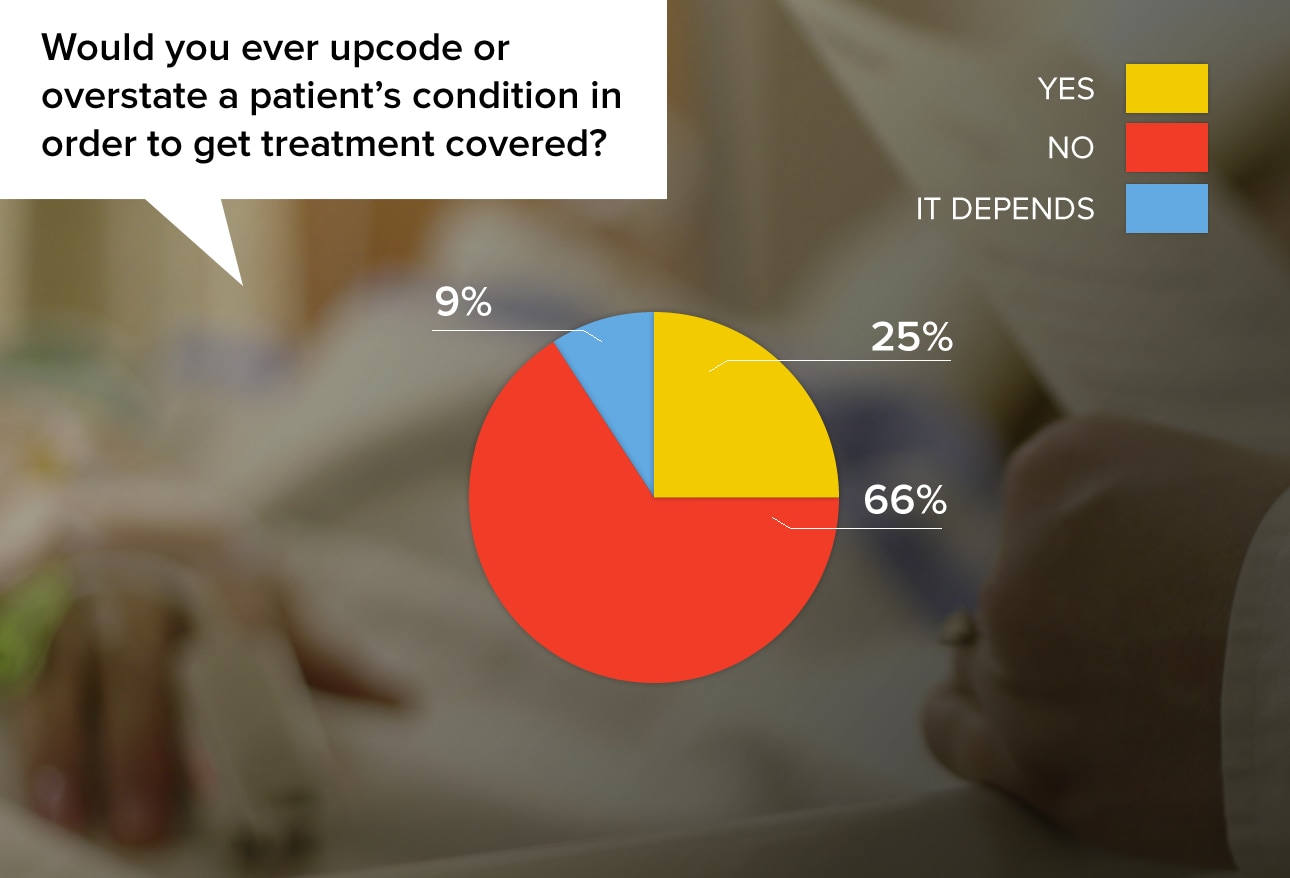

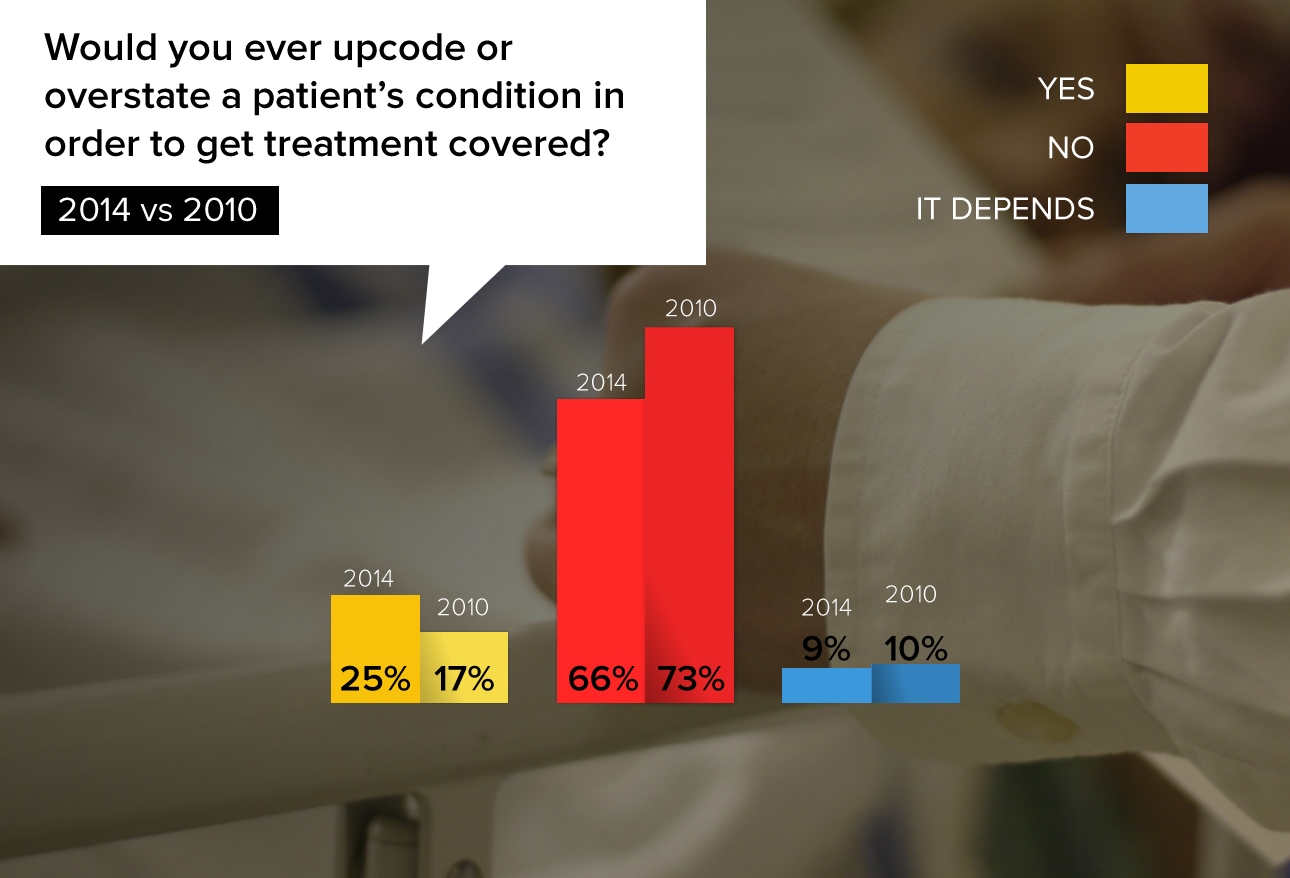

A quarter of physician respondents were torn between helping their patients by circumventing unrealistic rules and incorrect guidelines by insurers, and knowing that they could severely harm their own careers if they go too far.

"I would try to get the procedure covered and give the insurance company what they need. It's not like the insurance company has to look the patient in the face and tell them they can't get the service because of XYZ."

"There are times when prior authorizations are nothing but a blatant attempt on the part of the insurance company to deny a legitimate claim, and in those cases I'm going to go to town for my patients."

"Overstatement is a form of lying. If the insurer is making a wrong decision, then they need to correct, not withhold, treatment."

"It is dishonest, it is unethical, and it can also hurt the patient when/if he applies for life insurance or possibly other instances."

Upcoding gained some momentum since 2010; the percentage of physicians who said they would do this increased from 17% in 2010 to 25% in 2014. This may well reflect physicians' growing frustration with insurers. Slightly more men than women said they would engage in upcoding or overstatement.

"It depends on the seriousness of the condition and how necessary I felt the drug, treatment, etc. was."

"No, this is wrong no matter how you try to rationalize it."

"Yes. An example: a patient needed a head CT to see if there was a tumor or hidden strokes or hydrocephalus in a person with definite but mild cognitive impairment. Insurance would not pay unless the diagnosis was dementia. The patient did not have dementia (yet) and now is the time to make a diagnosis."

"Ethical nightmare. Most important is to help patient get appropriate care. The outcome of getting no care is worse than the upcoding."

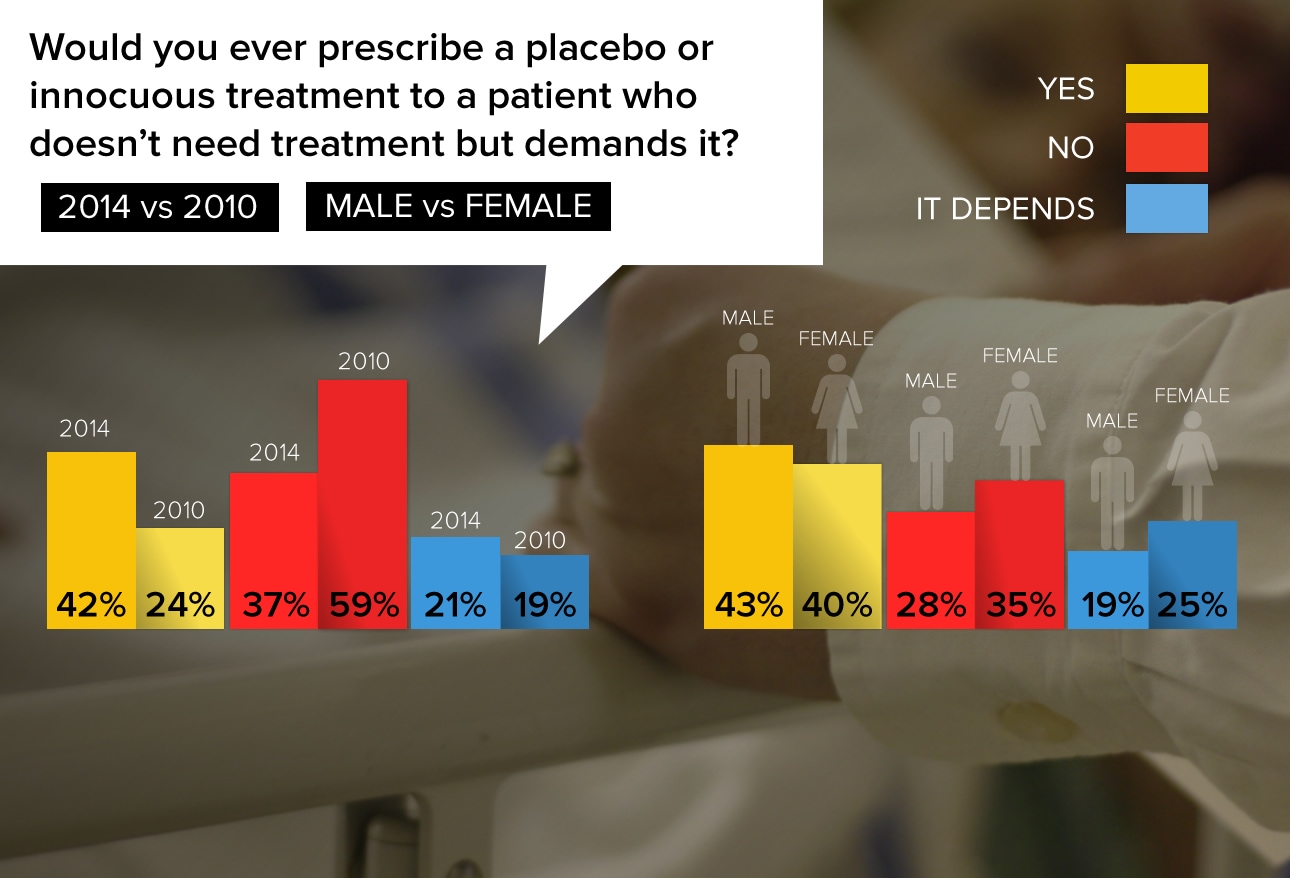

Practices are rife with patients who demand antibiotics for a virus, or treatments for a variety of symptoms that physicians believe will go away by themselves. But when patients are adamant, doctors often feel that a placebo treatment will be helpful.

"Yes, I need to keep those satisfaction scores up."

"Yes, the placebo effect has been clearly demonstrated to be real. With the pressure of time in outpatient care, this is one way to get them out the door and happy!"

"Sham treatment is not a substitute for communication."

"I did when I was younger and fearful of lawsuits, but as I aged as a physician, I told it like it was based on training and experience and said no."

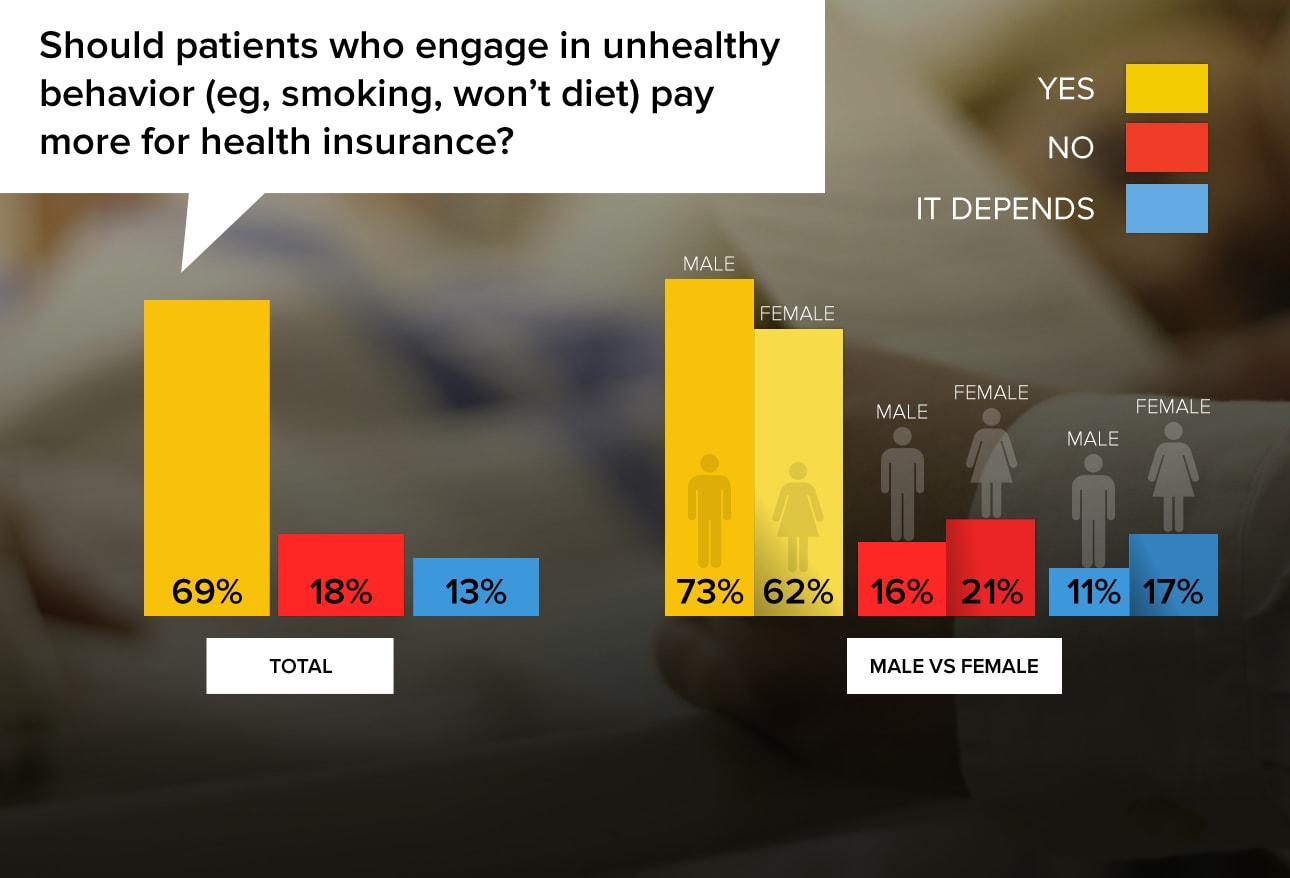

Given today's costly healthcare environment and the potential for doctors to be penalized for poor outcomes in nonadherent patients, the resounding majority of physicians feel that patients who don't take care of themselves should pay more for healthcare insurance.

"Not only yes, HELL YES!"

"Yes, in the same manner as bad drivers have to pay higher auto insurance."

"This way, patients will become more motivated to follow medical advice and treatment, and hopefully their premiums go down to a regular rate when they quit smoking or lose weight."

"Why should someone who takes care of themselves as best they can pay the same rate as those who abuse themselves and are a drain on the system?"

"I did not go into medicine to make judgments on patients' behaviors. Where do you draw that line as you sit in judgment?"

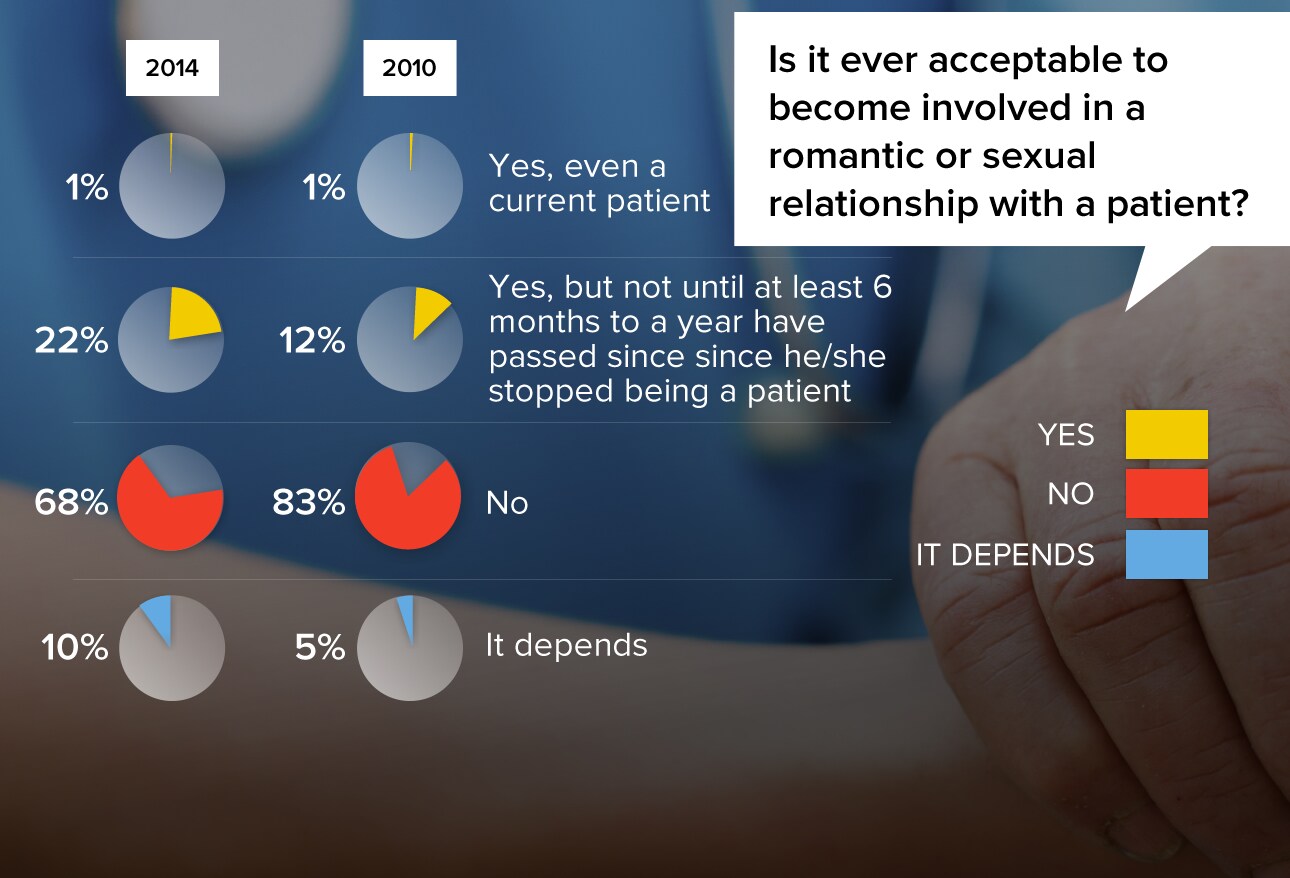

Since 2010 when Medscape first asked this question, there's been a modest shift in thinking regarding the appropriateness of romantic relationships with patients. In 2010, only 13% of respondents said it was acceptable (either with a current patient or after 6 months), compared with 23% in 2014. And the percentage who flatly say "no" has fallen from 83% to 68%. Among European physicians, 21% of respondents say that it's OK to have a romantic relationship with a current or recent-former patient.

"Love should not be denied. But you should immediately and formally sever the patient-physician relationship."

"To do so betrays everything you stand for as a physician."

"Of the many arguments against, only a fool would take the medical-legal risk. It's a great way to get in trouble with your license."

"I've seen successful marriages arise out of initial doctor-patient relationships."

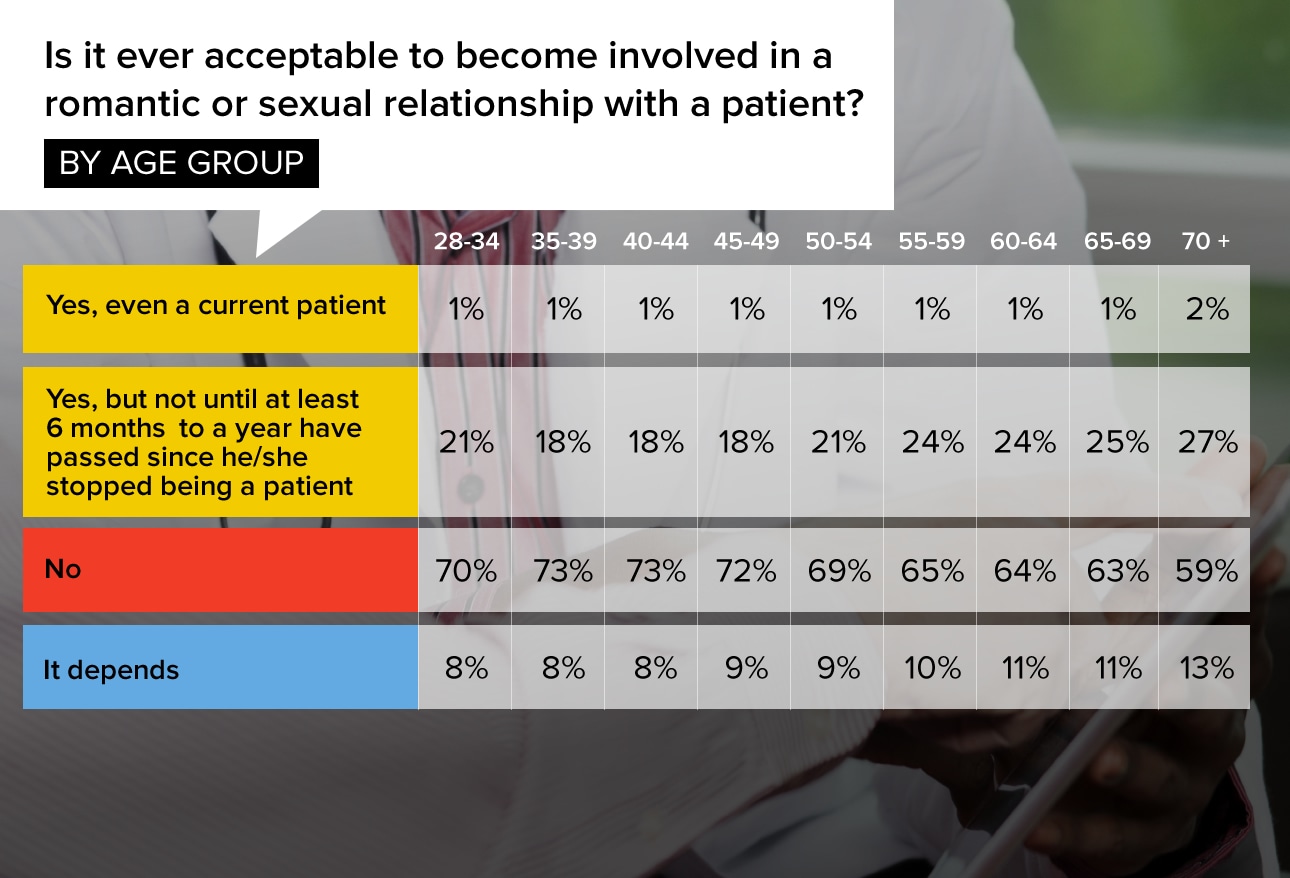

Physicians of all ages are overwhelmingly against becoming involved with a current patient. However, as doctors age, they are more apt to find it acceptable to date someone who stopped being a patient at least 6 months ago.

"Physicians are allowed to fall in love but should be careful that the patient is not misled."

"You should allow time for feelings to cool off and see if the attraction was simply a result of the power imbalance inherent in doctor-patient relationships!"

"If both of us were single and were attracted to each other, I don't see any reason that this would be unethical. I think it might be awkward or uncomfortable but not unethical."

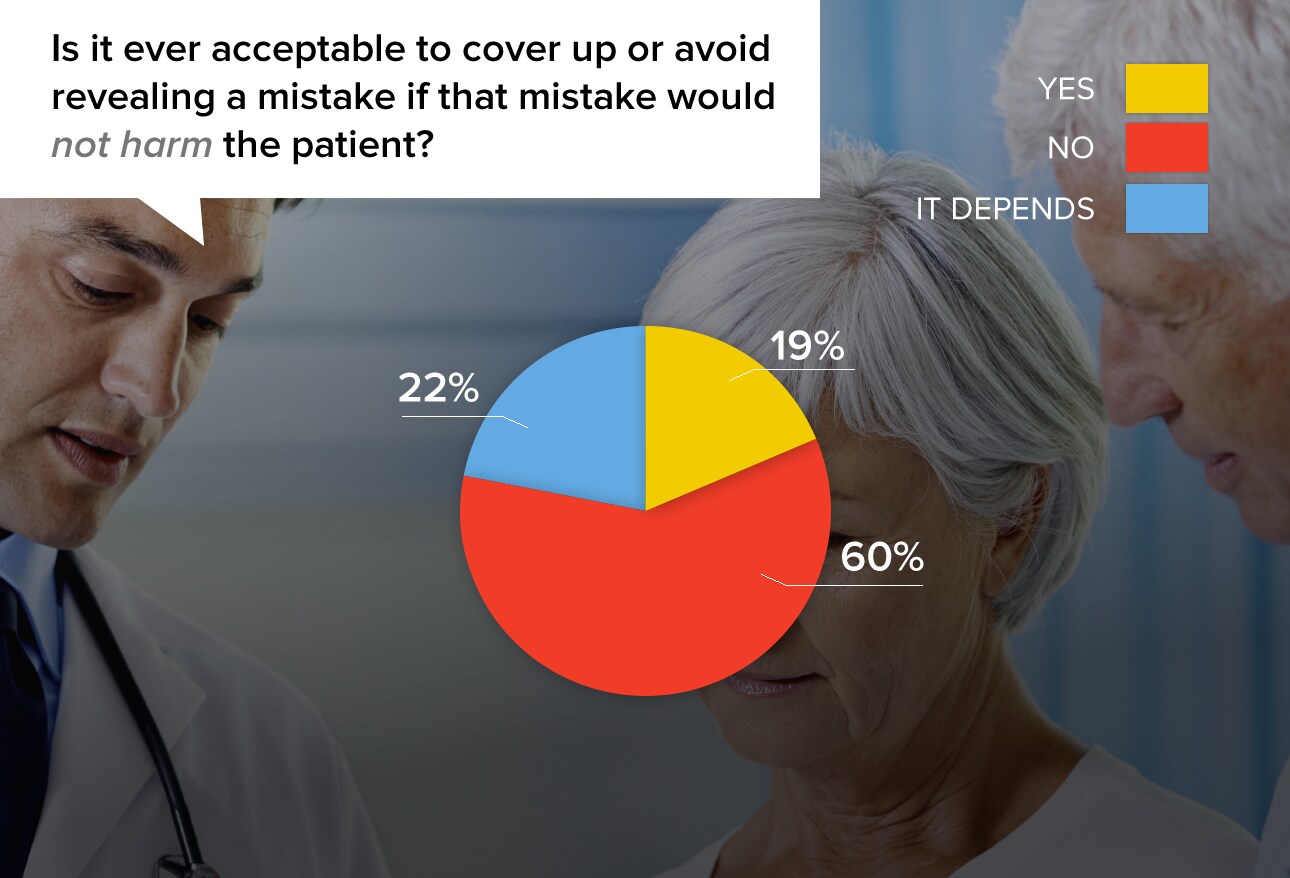

With an estimated 85,000 medical malpractice lawsuits per year, it's understandable that physicians are leery of creating more situations where patients are concerned about mistakes, even ones without repercussions. Still, responses show that physicians often feel uncomfortable keeping such information to themselves.

"In general, the truth will get out, so it's probably best to have fully informed patients."

"Sometimes the consequences of a mistake are not apparent at the time it occurs."

"The harm of explaining a merely bureaucratic error can cause a patient to lose confidence in his treatment."

"When in doubt, the best policy is complete honesty as soon as possible."

"Patients don't need to know something that isn't or will not be important. Docs have enough stupid liability."

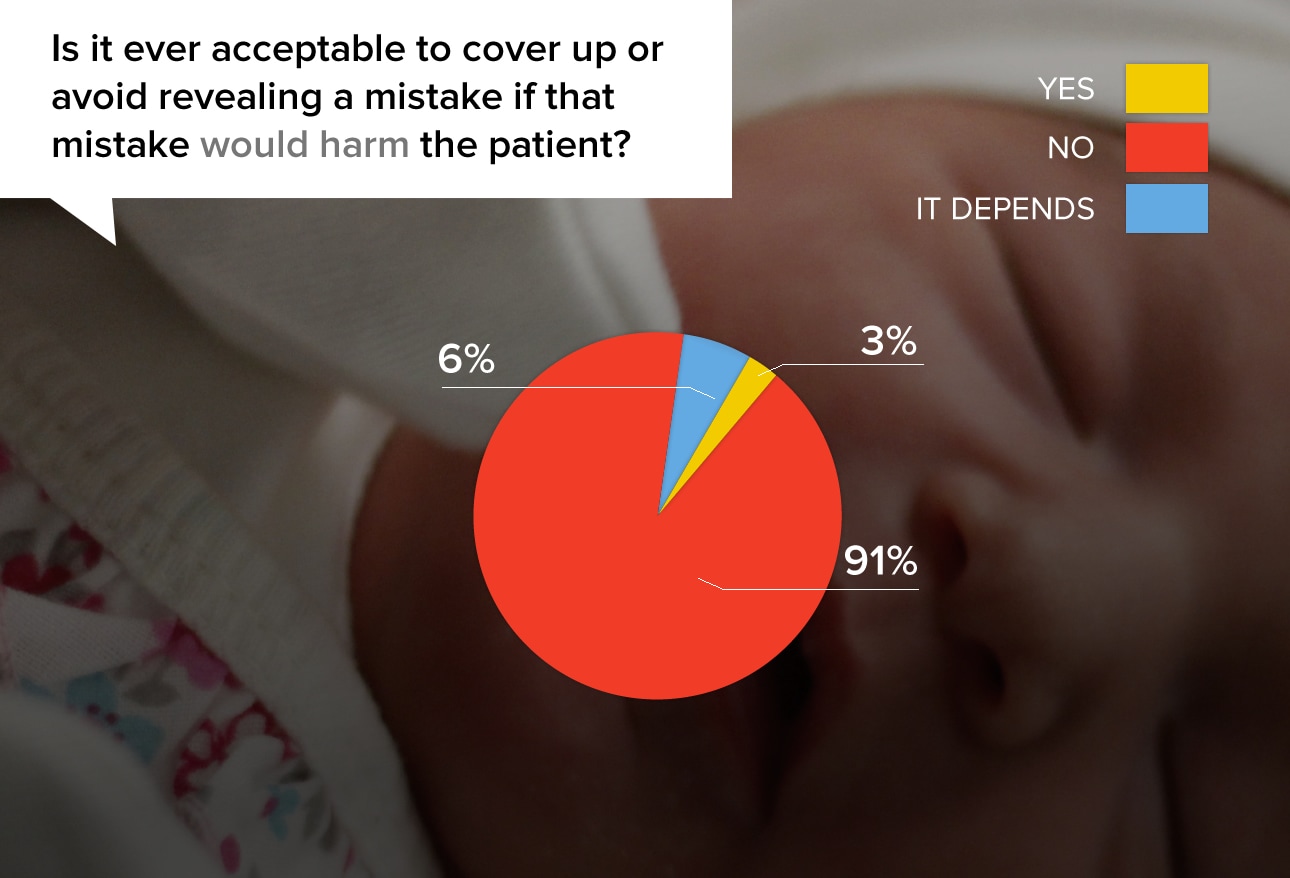

On the other hand, despite the malpractice threat, physicians are adamant that it's right to reveal mistakes that would cause harm to the patient. Many doctors noted that actively covering up a mistake was wrong, yet they admitted that they might not initiate disclosure of it for fear of repercussions.

"The patient and family need to know that a mistake has resulted in a change in course that poses harm to the patient."

"It is the best (and the right thing!) to let the patient know. Covering up can only lead to more problems and is unethical."

"If you are already on shaky ground at your hospital or know your own career or future is in jeopardy, I would avoid disclosing. You must practically weigh the risk vs benefit. NO sane person (even a doctor) sticks his hand into a burning fire if he has done so previously & been burnt!!!"

"Get us tort reform and I will change my vote."

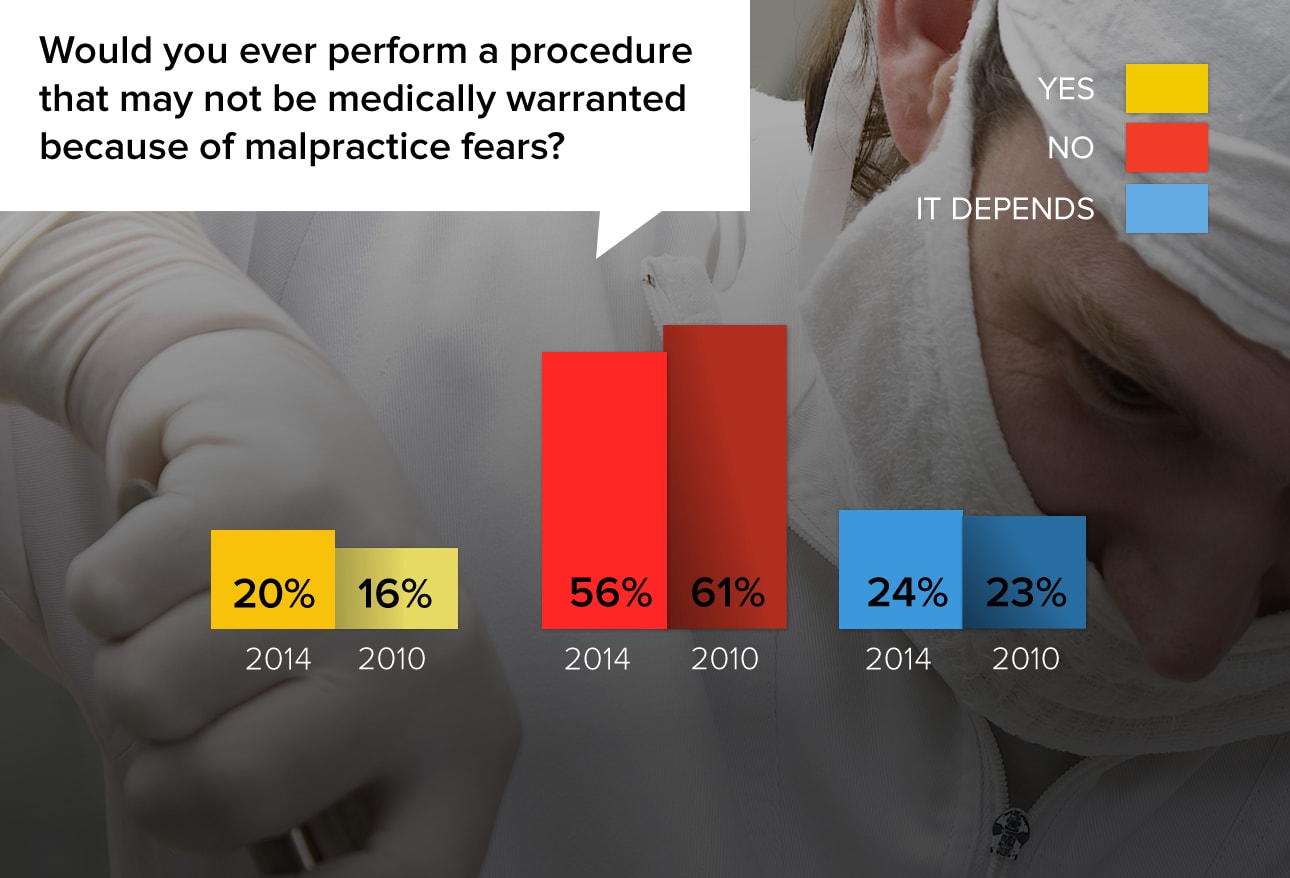

Defensive medicine and malpractice costs have been blamed for adding at least 2.4% to the cost of healthcare. Physicians know how destructive and disruptive lawsuits can be and will take serious steps to avoid being targeted. While so-called apology laws can help in some circumstances, many physicians practice defensive medicine to try to make sure they're never in that situation. Very slightly more physicians would practice defensive medicine now than in 2010.

"I would explain the pros and cons and let the patient decide."

"On occasion, I have gone further with diagnostic testing than I thought really necessary, because the patient or family was hostile and likely to be quick to sue."

"There is more and more push to avoid doing CT scans and some labs. The one time I did wait, the patient ended up having a subdural and I wished I had ignored all those new guidelines."

"This question makes me think of liberal biopsy practices of skin lesions that look benign. I will often decide to biopsy the lesion 'just to protect myself.'"

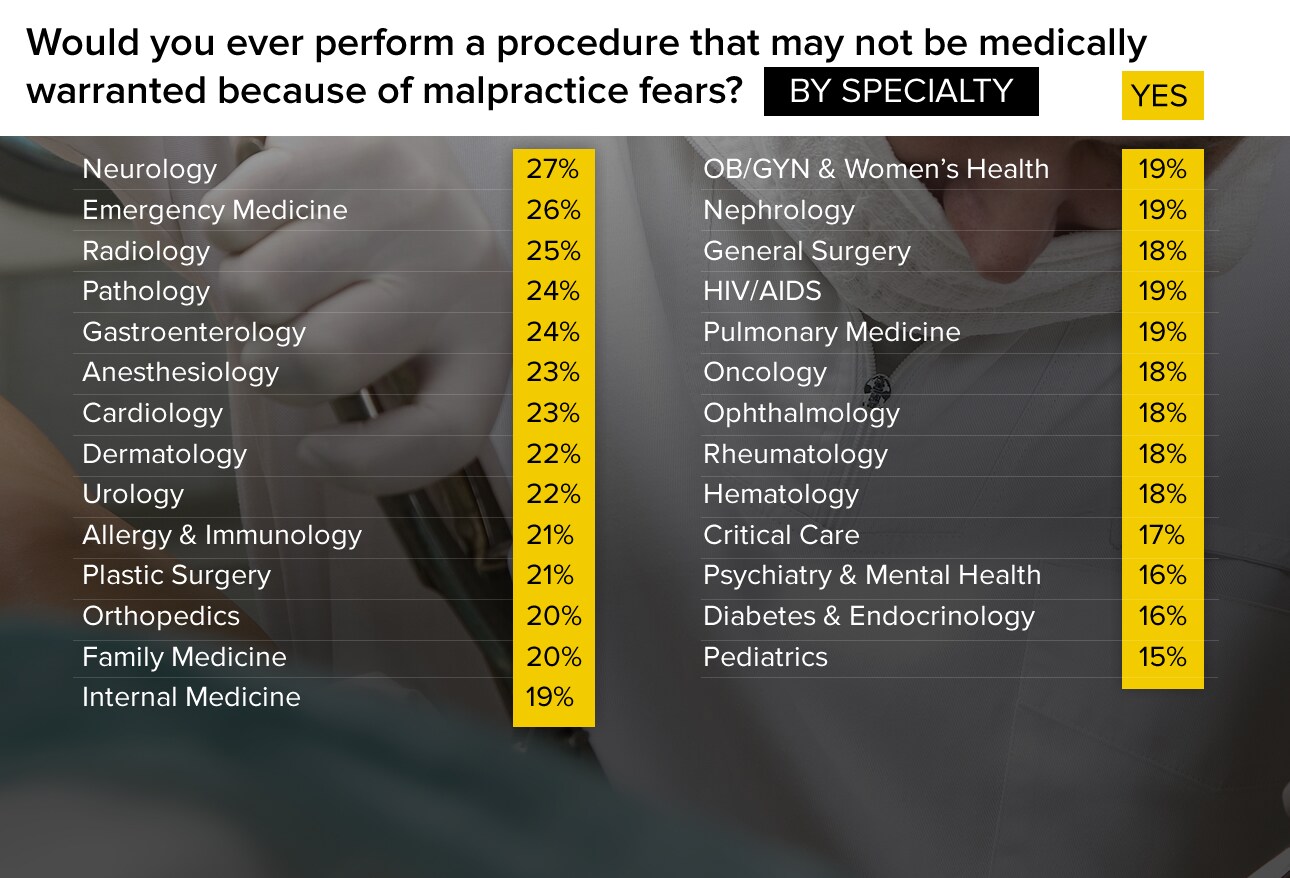

There's a significant difference among specialty groups in terms of how likely they are to perform defensive medicine. The specialties most likely to do so—neurology, emergency medicine, and radiology—were about 10 percentage points higher than the lowest: psychiatry, endocrinology, and pediatrics.

"Sometimes you have to protect yourself."

"Yes, but nothing invasive; more likely a lab or radiology procedure."

"Society and leaders expect that doctors bear the burden of cost cutting but give no protection against lawsuits that could completely devastate them financially. It's absurd."

"I would be more likely to NOT perform a procedure in that situation."

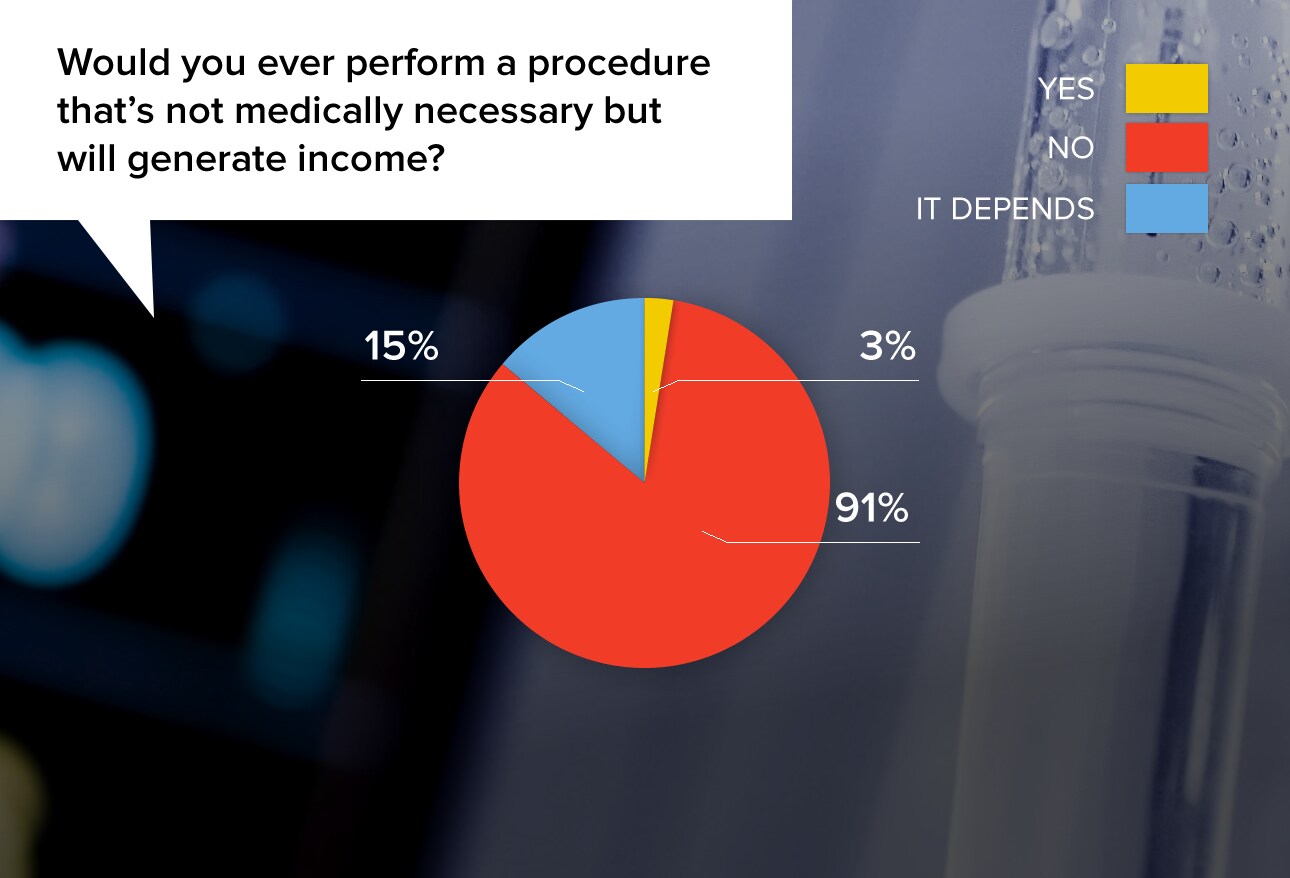

Physicians differentiated between cosmetic procedures (which are not medically necessary but may enhance quality of life) and unnecessary procedures done purely to boost income.

"Botox, laser hair removal, plastic surgery, and hair transplants all fit this category. They improve quality of life but are not medically necessary."

"That is the definition of immoral, to get income from unneeded treatment. I make much less money than my unethical colleagues who do this frequently."

"I know far too many doctors who do just this sort of thing. I have left practices because of pressure to operate on patients who do not need surgery."

"I have struggled with the medical necessity of some procedures and I try to avoid them if I conclude that I am the only one that can potentially benefit from it."

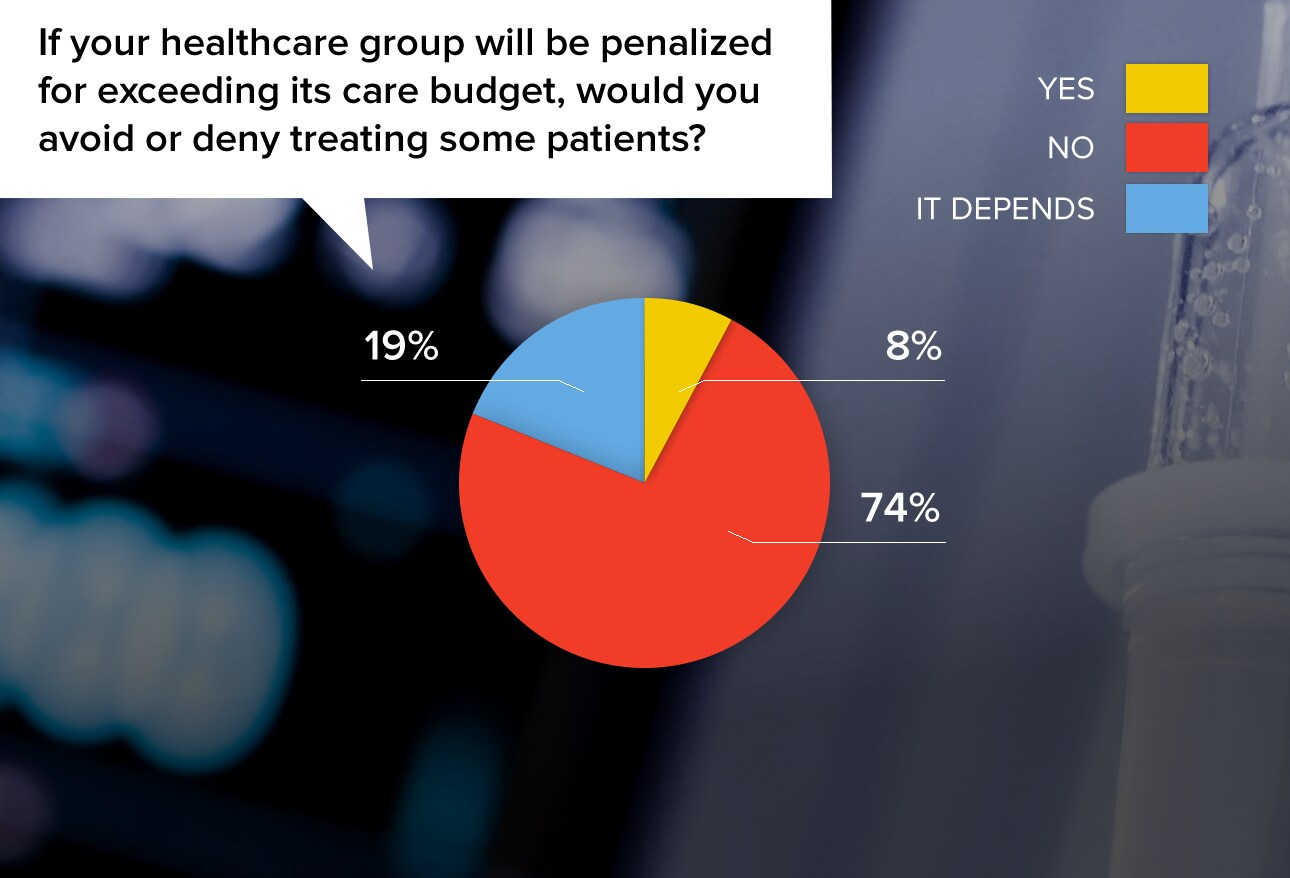

As more and more hospitals and healthcare systems have gainsharing programs or programs that involve penalties for exceeding budgets, there is an increasing expectation of withholding elements of care. How much will doctors bow to the pressure?

"Withholding indicated treatment to save the organization money is the antithesis of ethical practice."

"I treat patients, not the insurers. I'd rather be dismissed by the organization than injure the patient."

"We all need to keep costs under control; avoiding unnecessary treatment is a positive move."

"I would avoid taking on higher-cost patients; I would not deny treatment to current patients."

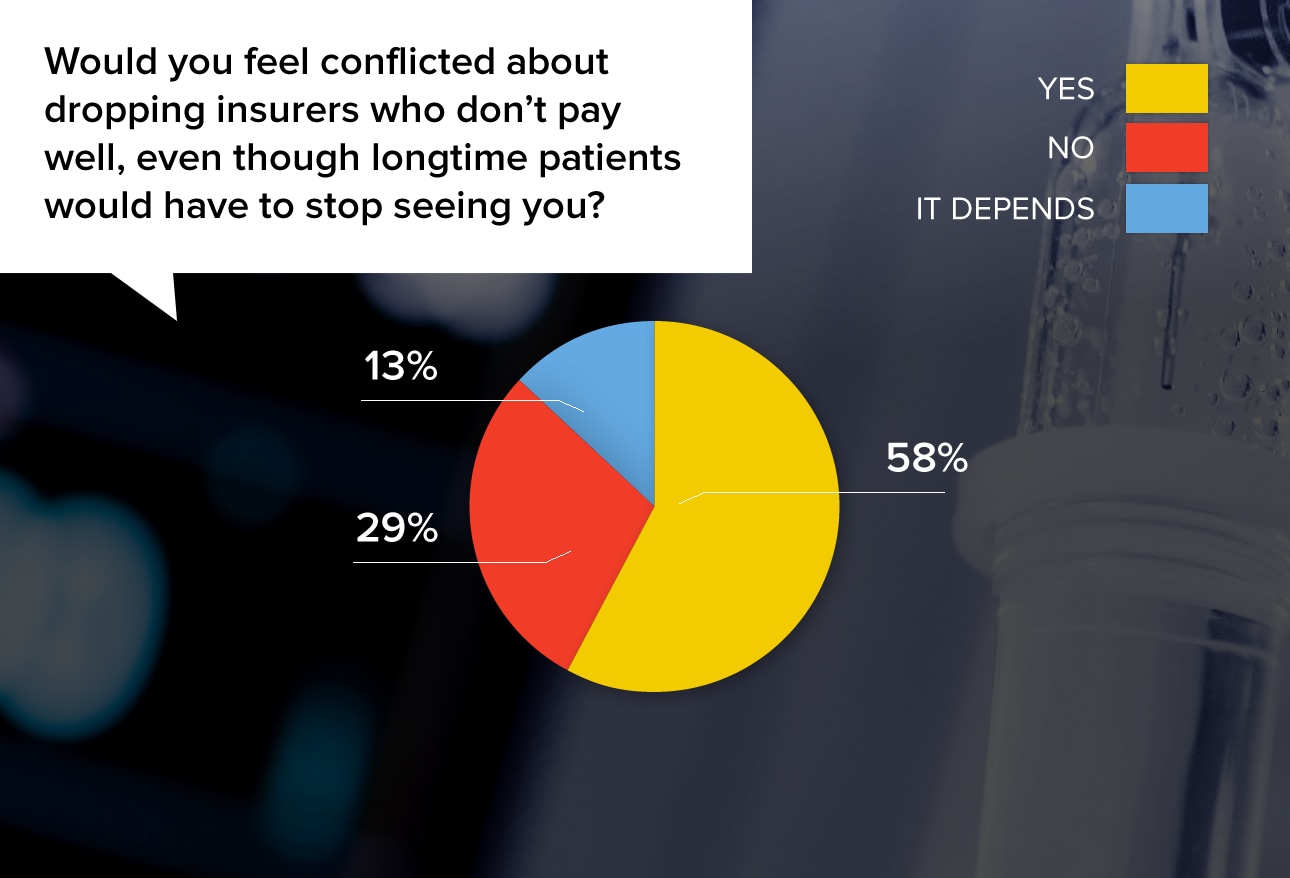

Physicians facing this situation typically try to balance the realities of business with the desire to help patients. Some physicians make special discount-fee arrangements and others treat noninsured patients after hours, but many feel that there is no choice but to let the patient leave the practice.

"This is a no-win situation. If you don't survive financially, you won't be seeing any of your patients. I am certain I am not the only physician who could help them."

"Money, of course, is important, but doctor-patient relationship/confidence is priceless and a long-time journey."

"Why should I feel bad about getting paid to do my job? As long as I'm not getting greedy."

"I'd feel a momentary sadness. The patient can always change insurance plans or pay out of pocket. They can switch coverage if they want to see me. Patients have choices; so do I."

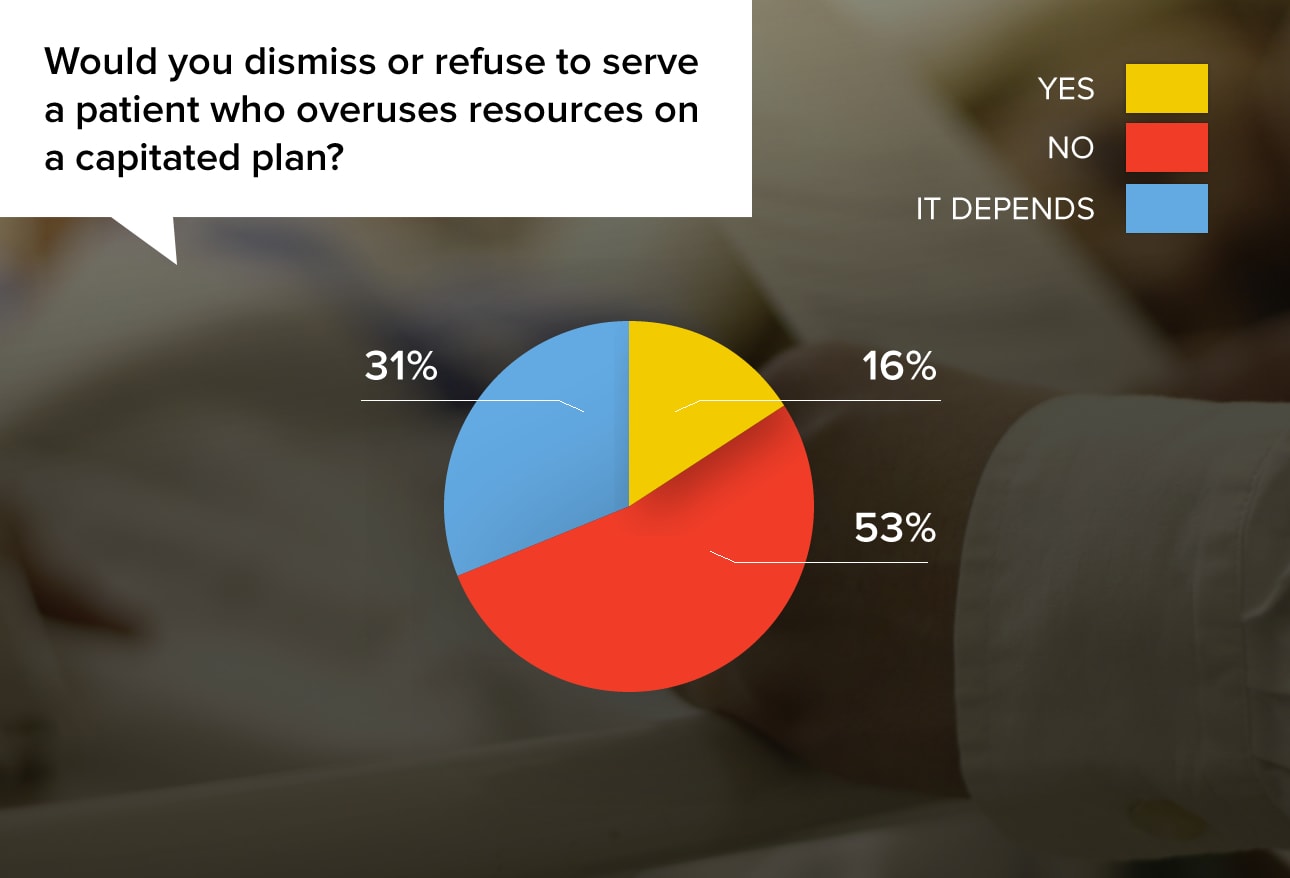

While about half of physicians (53%) flatly refused to be influenced, it's interesting that almost half said they would or might dismiss such patients.

"Health is not the mathematical average of capitation plans."

"No, I would have a heart-to-heart discussion with the patient instead."

"Sometimes people who abuse the system have to be educated, and if that doesn't work, dismissed."

"If a patient overuses resources that are not medically justified, I would first talk to the patient, and if behavior continued, I would dismiss/refuse to serve that patient."

"I am not fond of patients who seek medical assistance without reason."

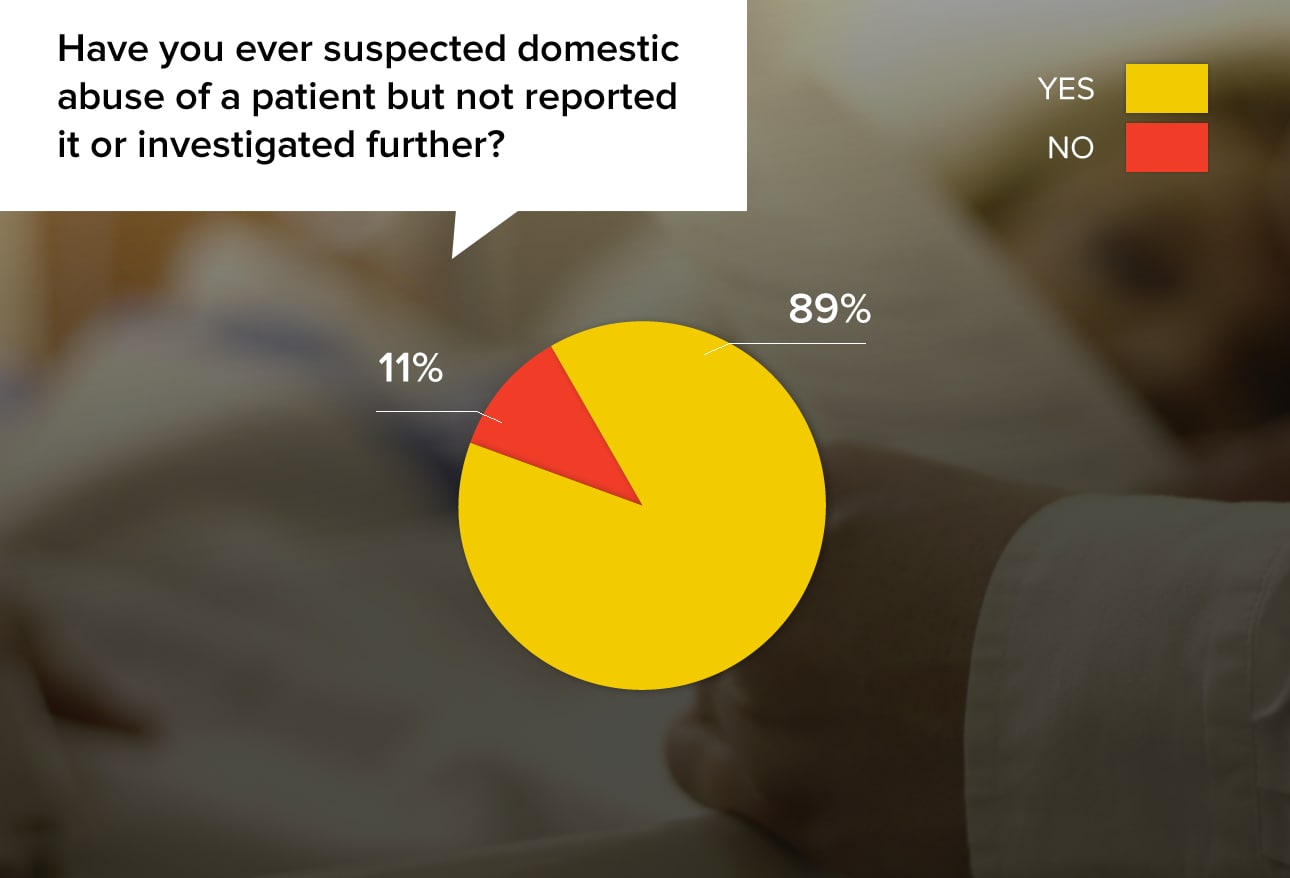

An overwhelming 89% of physicians answered "yes." Doctors say that dealing with domestic abuse can open up a can of worms; many noted that they reported situations that they suspected, which ended up damaging the lives of people who were falsely accused. And sometimes the doctors' own lives were damaged in the fallout. Other physicians said they were glad to have brought an end to dangerous situations.

"I suspected it, but the patient denied it. I observed closely but found no additional evidence so I did not report it."

"A young lady I felt was being sexually abused by her stepfather but denied everything, even with him out of the room. I so wanted to get the truth out of her, both to help her and to stop what I was 99% certain was sexual abuse. She was 18, so a legal adult, but she still had a minor's maturity and I believe was mentally imprisoned. I went home and needed a shower after that shift."

"I did, in fact, suspect abuse in one lady. I found out later that her story of an accident was verified by independent witnesses."

"I have always made sure to ask the patient in private, but if they lie to me, there's nothing I can do. When I have more proof, I do something about it."

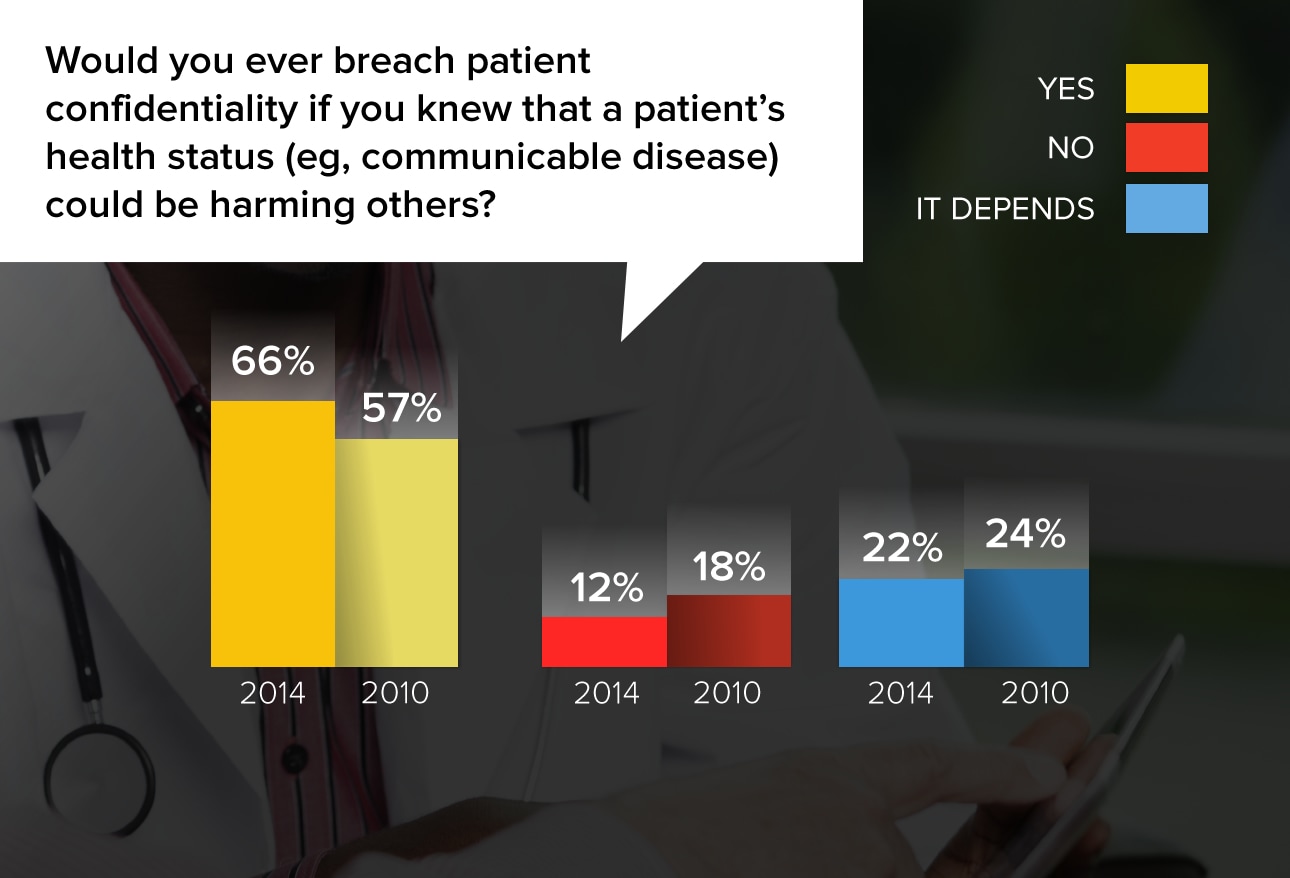

Sometimes ethical dilemmas involve competing principles, each of which has a positive aim. This issue pits confidentiality against the common good of society. Physicians' attitudes toward social responsibility for the greater good have changed since we asked the question in 2010. At that time, only 57% of physicians said it was acceptable to breach patient confidentiality; now it's 66%. European physicians were a little less likely to say they would do the same.

"I tell the patient that if their significant other asks if they have a communicable disease, I will tell them."

"Years ago I encountered a patient who was HIV positive and was engaging in unprotected intercourse. I asked a nurse to accidentally let the patient's partner know that his behavior was putting him at significant risk, given her status."

"Public health trumps patient confidentiality every time."

"We have obligations to all of our patients, not just to one. Patients who present a clear and present danger to others (homicidal intent, TB, HIV, etc.) need to be reported to public health."

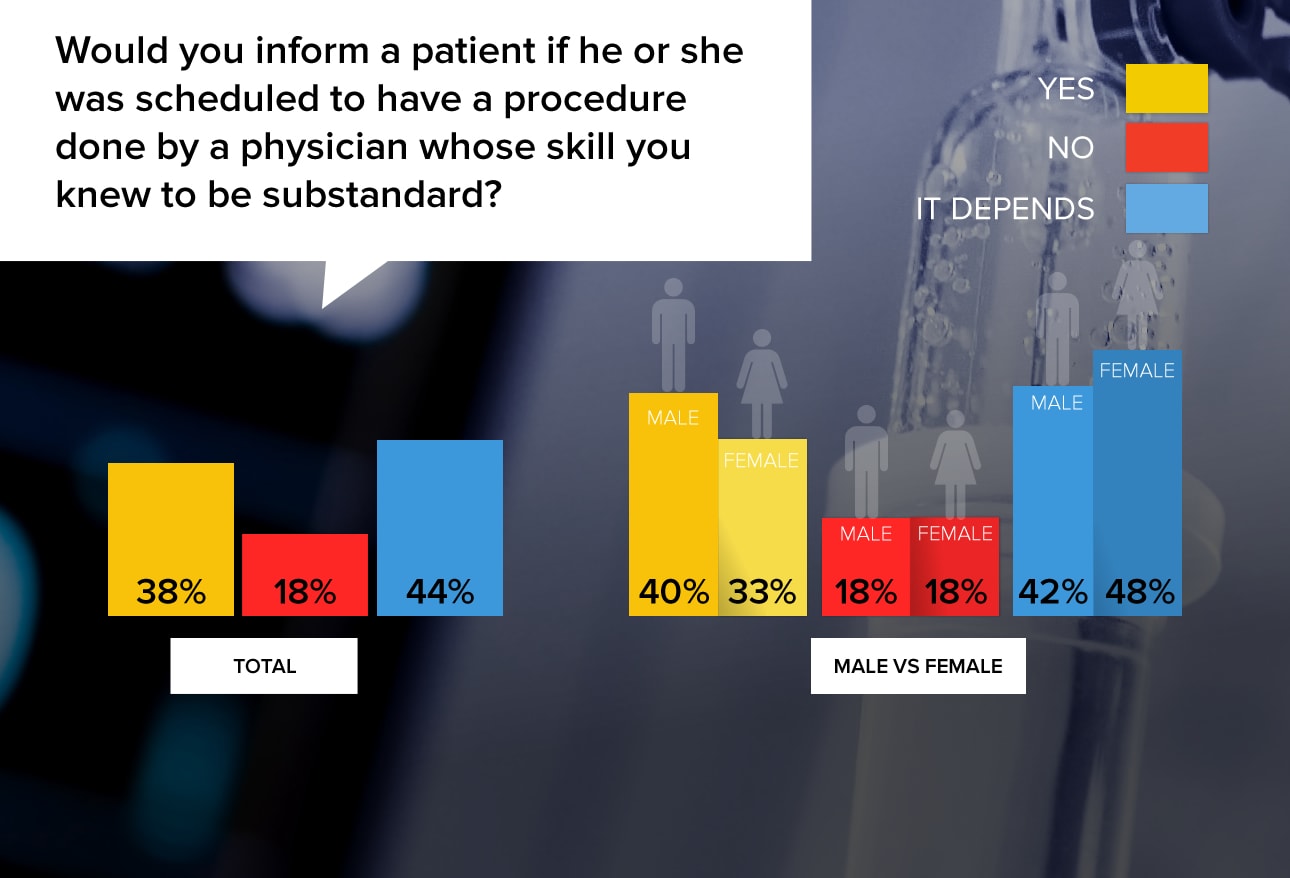

For many physicians it's difficult to draw the line between loyalty to the profession and safeguarding their patients.

"One has to be careful due to slander laws, but the patient is more important. I would urge them to have their care elsewhere, with as little direct criticism of the doctor involved as was necessary to accomplish that."

"I would only say something if they sought out my opinion in a professional setting."

"Very carefully and only if I had evidence such as direct experience (not hearsay)."

"I'd be reluctant to throw another physician under the bus unless they are truly dangerous."

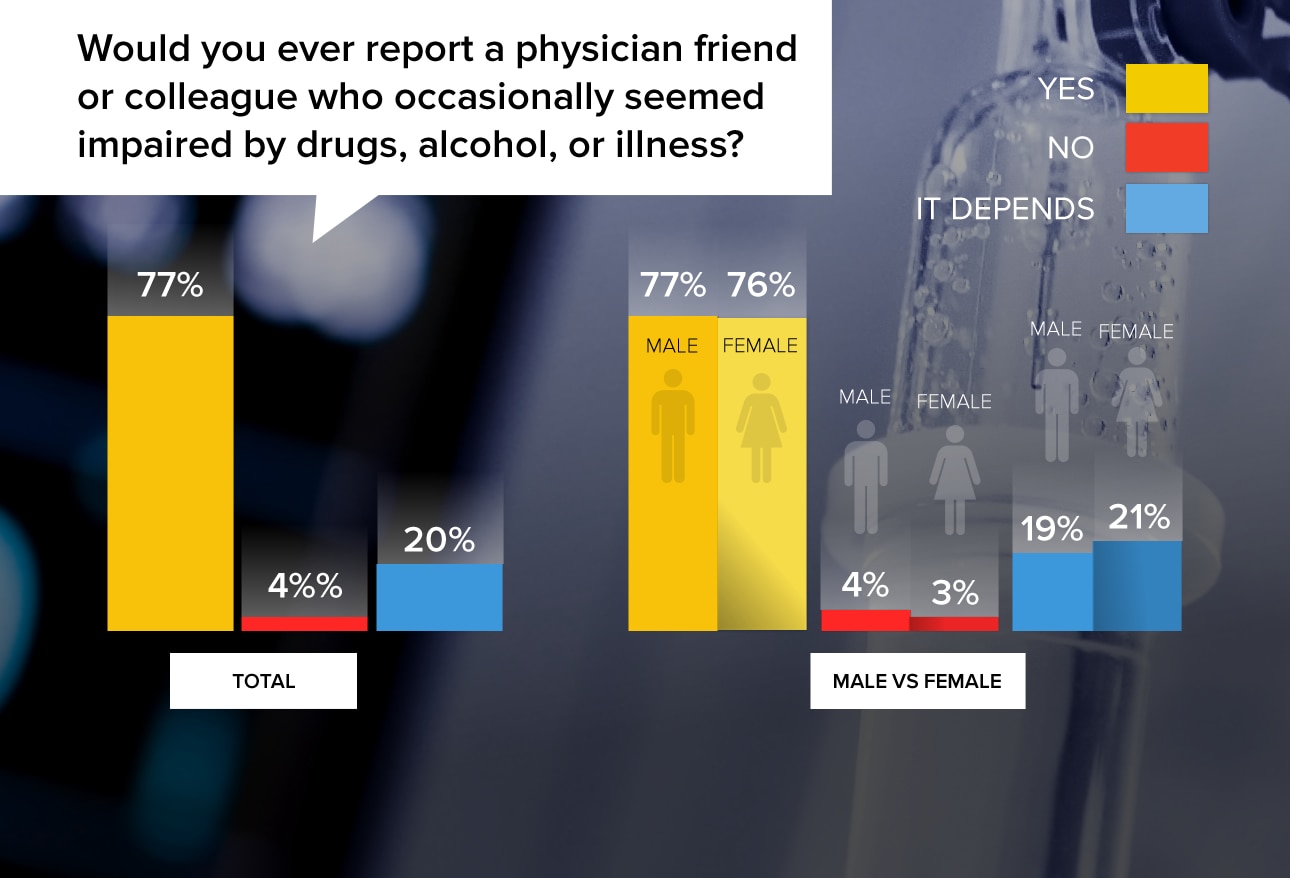

More than three quarters of physicians said they would report an impaired colleague, but most stipulated that they would speak to the person in question first and would encourage him or her to get help. Many doctors mentioned that they have reported a colleague and found it difficult emotionally, although they knew they were doing the right thing.

"We are to do NO harm, this means to our patients and to ourselves. By enabling an impaired colleague we are INDEED doing harm."

"After I have spoken to them and warned them to get help...if they would not seek treatment or change, I would turn them in."

"I have reported a friend—not a friend anymore, but I had to; they would not seek help when I spoke to them personally, and the care of patients was in serious jeopardy."

"I would now, but I have not done it in the past when I was junior to the doctors involved."

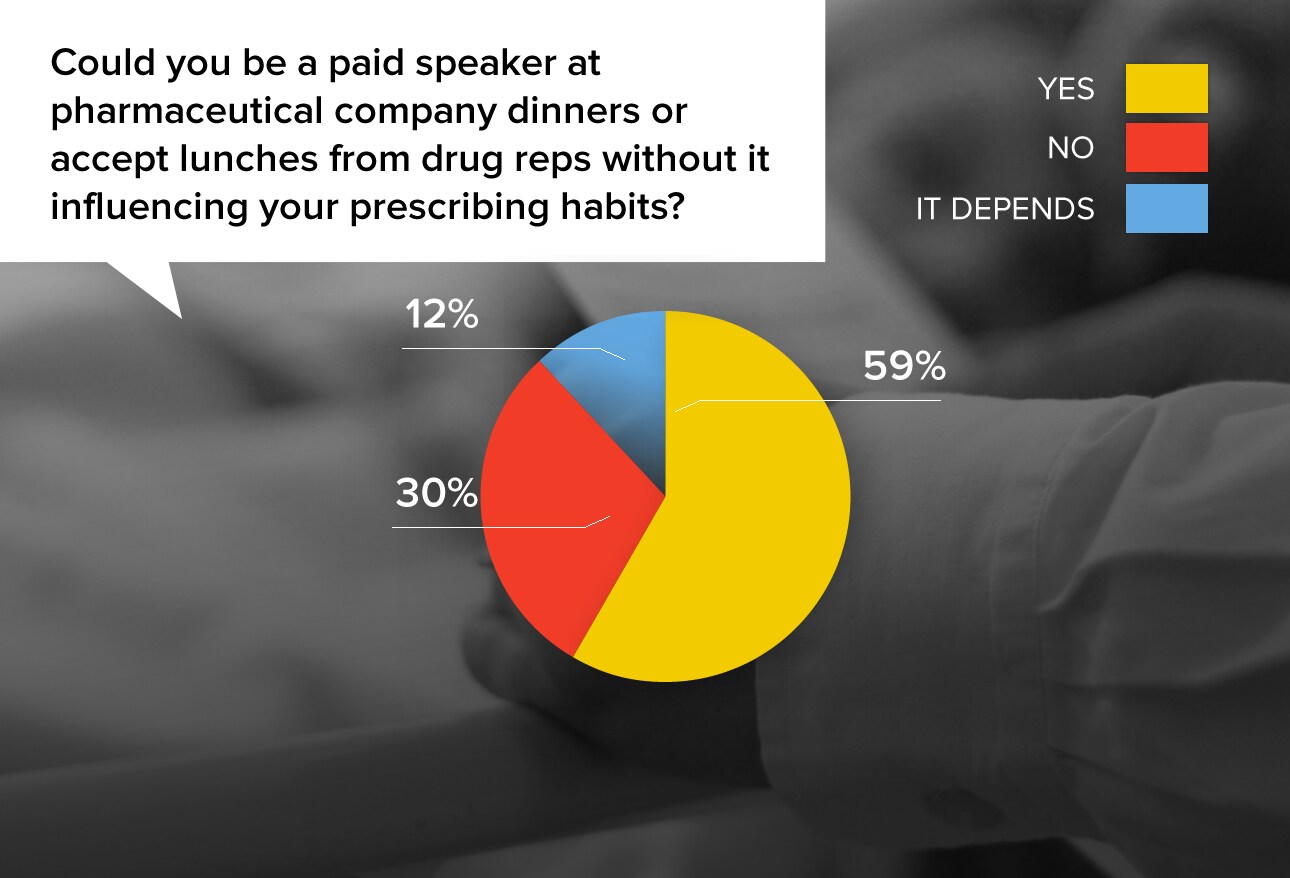

Most doctors were indignant that people would think they could be so easily bought. Others felt that they obtained more in-depth drug information than they would gain simply by reading the drug literature. But almost a third of doctors felt that people who say they would not be influenced in that situation are just kidding themselves.

"None of my treatment decisions have been made based on a $5 sandwich. I don't use some types or brands of therapies because they are not appropriate, period. And I use some more than others because they are more effective, more affordable, better tolerated, etc."

"Good medications may not speak for themselves. If I believe in a good drug, I want to spread the word. I welcome the drug companies' reasonable support to be able to provide communication to other physicians."

"This is clearly a conflict of interest. It is almost not possible to stay neutral."

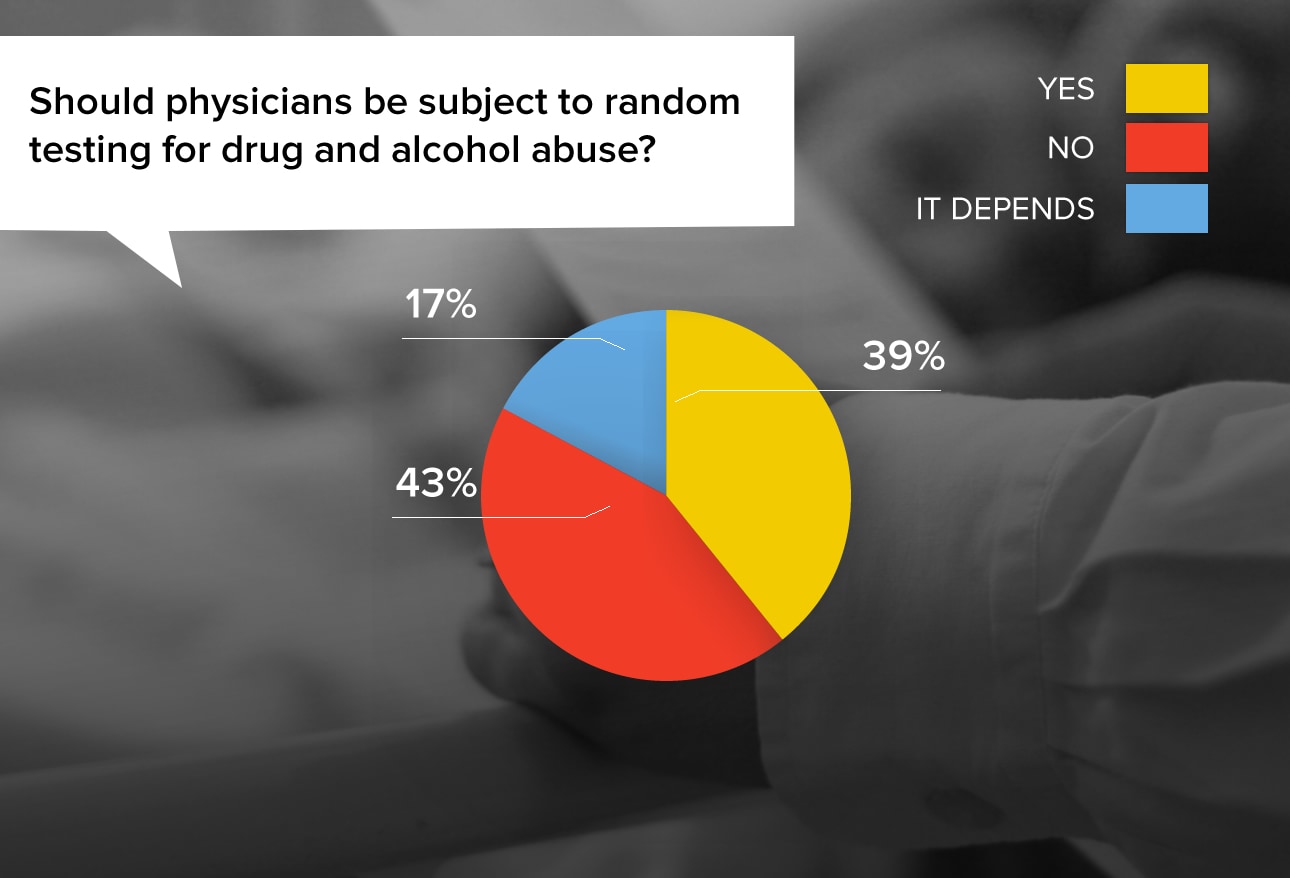

This issue evokes strong emotion among physicians, with many considering drug testing useful and others seeing it as an invasion.

"Shouldn't anyone who works in a critical profession (airline pilots, surgeons, astronaut, etc.) be tested before they end up hurting themselves and other people?"

"Yes, because drugs and alcohol impair medical judgment and place patients at risk."

"I think physicians are persecuted enough as it is."

"I think we should police our own. Keep the administrators out of it. If there were a way that doctors could do this, more doctors would seek help."

"The incidence does not justify the cost. Most abusers are caught because of behavioral abnormalities."

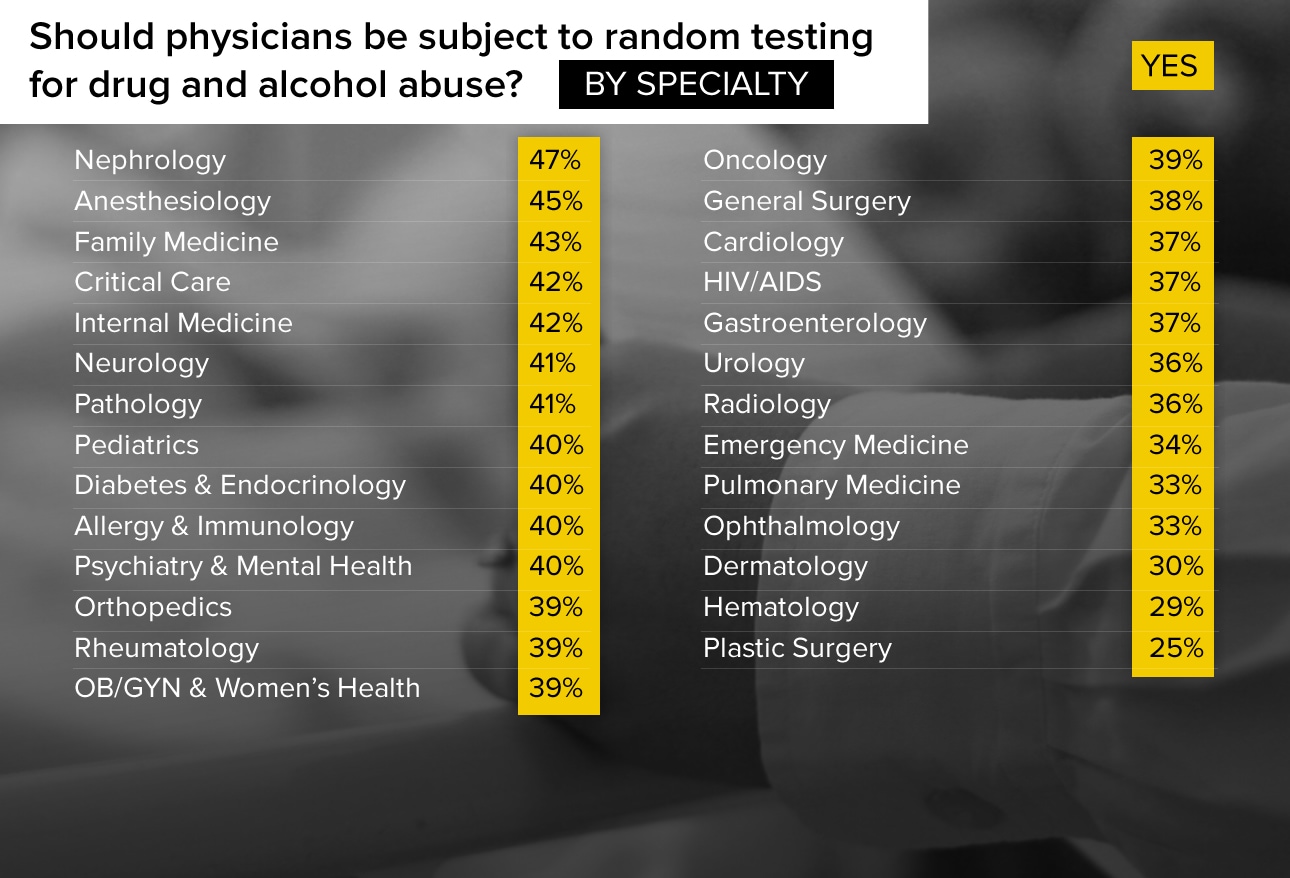

There's wide variation by specialty as to whether physicians should be drug-tested. At the top tier, nephrologists (47%) and anesthesiologists (45%) were the most supportive of this measure; hematologists (29%) and plastic surgeons (25%) were least supportive.

"We work in a profession with great responsibility that extends beyond a simple office visit. The consequences of bad decision-making or bad prescribing from a colleague under the influence can affect a patient for years to come."

"I think random drug testing is a violation of personal freedom."

"Yes, but there should be a legitimate reason and forewarning for all involved."

"Trying to guide a patient to appropriate care without defaming the doctor. The patient is pleased with but does not realize that their own doctor has not been addressing, treating, or is neglecting issues that could be life-threatening now or in the near future."

"Being asked by superiors to make decisions based on externalities (eg, for cost-saving reasons)."

"Disclosing a patient's condition that will harm others."

"Having to do procedures that I don't feel are needed but which the community comes to expect."

Medscape Ethics Report 2014, Part 1: Life, Death, and Pain

Medscape Ethics Report 2014, Part 1: Life, Death, and Pain What Do You Think About Physician Ethics?

What Do You Think About Physician Ethics? Medscape Employed Doctors Report: Are They Better Off?

Medscape Employed Doctors Report: Are They Better Off? Residents Salary & Debt Report 2014

Residents Salary & Debt Report 2014 Medscape EHR Report 2014

Medscape EHR Report 2014 Best & Worst Places to Practice 2014

Best & Worst Places to Practice 2014