Medscape Ethics Report 2014, Part 1: Life, Death, and Pain

Leslie Kane, MA

December 16, 2014

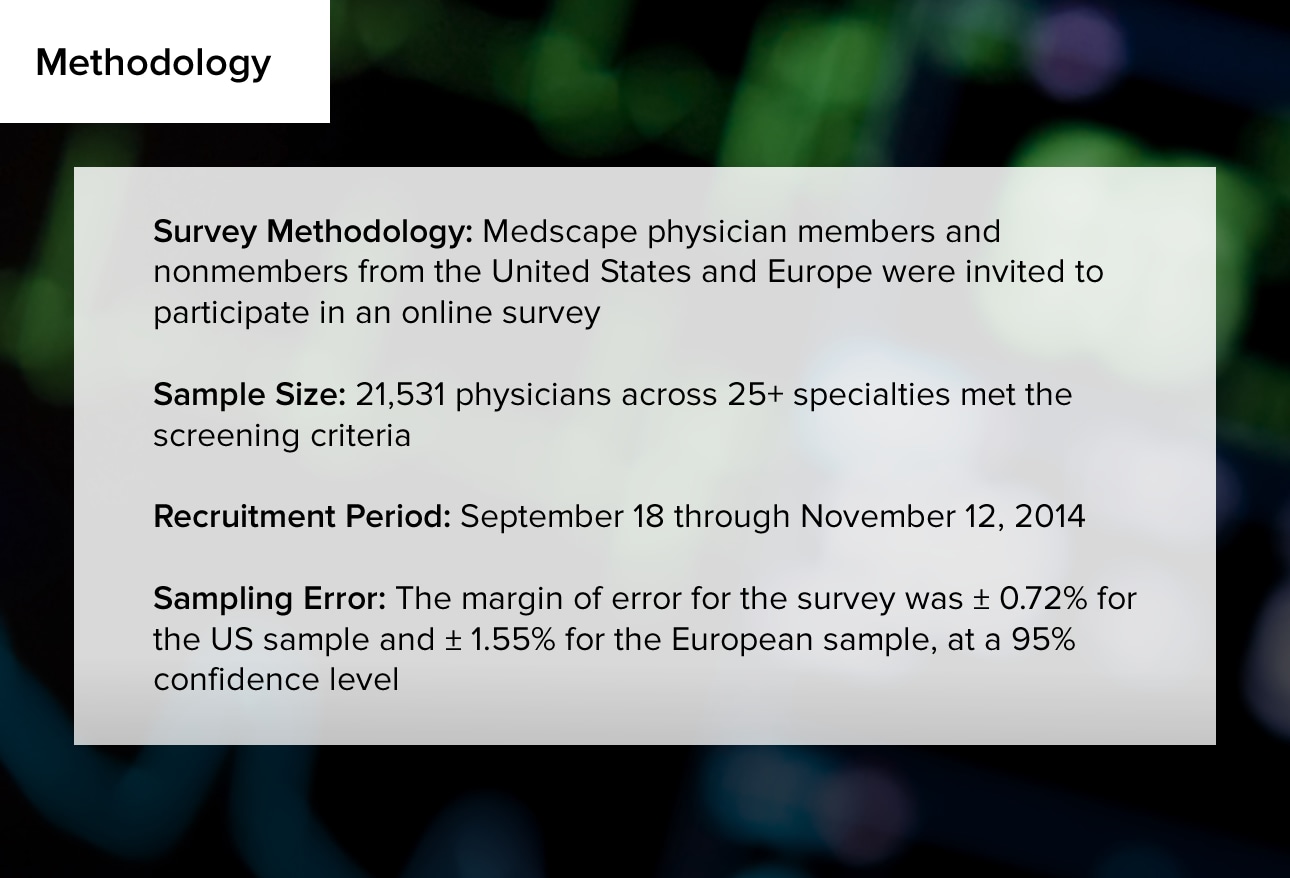

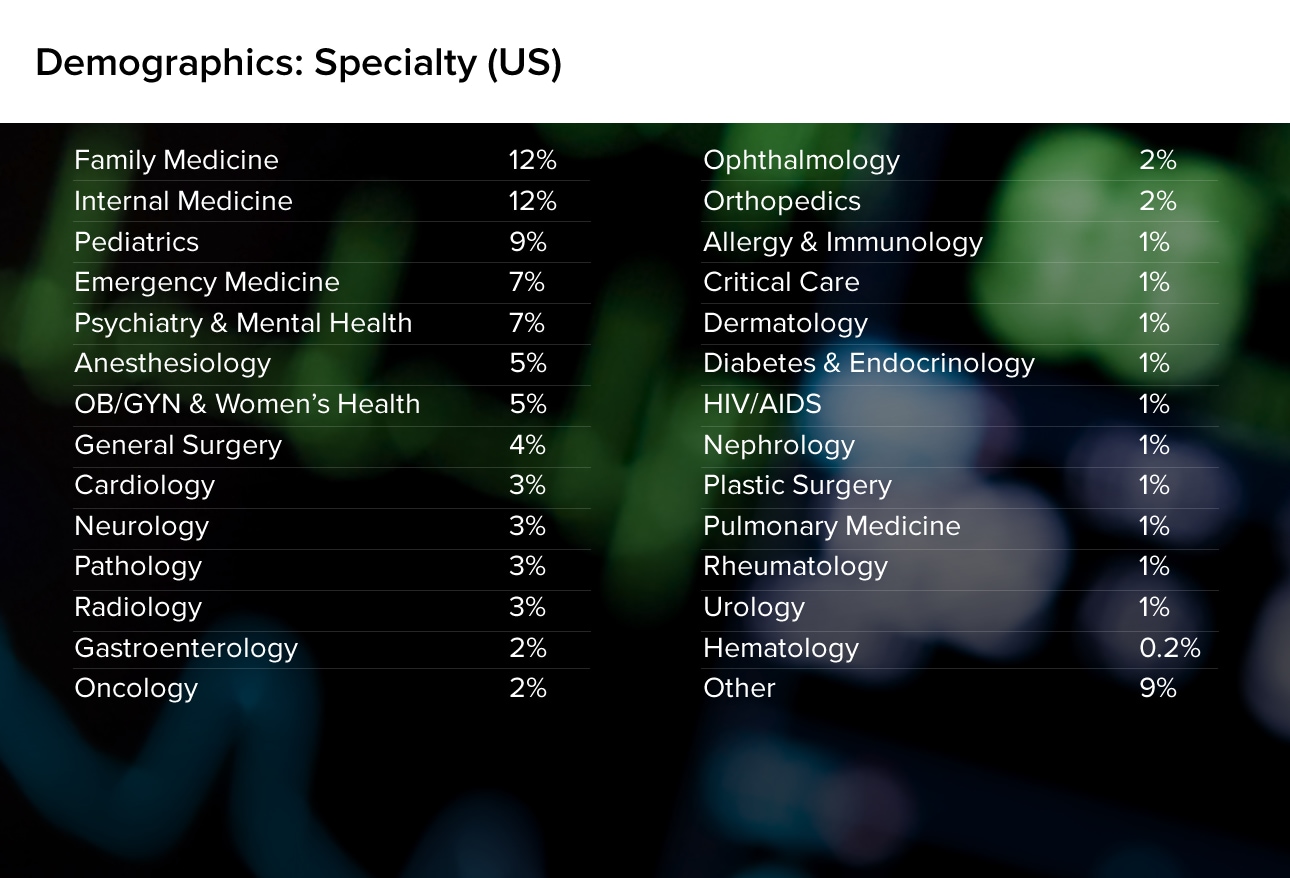

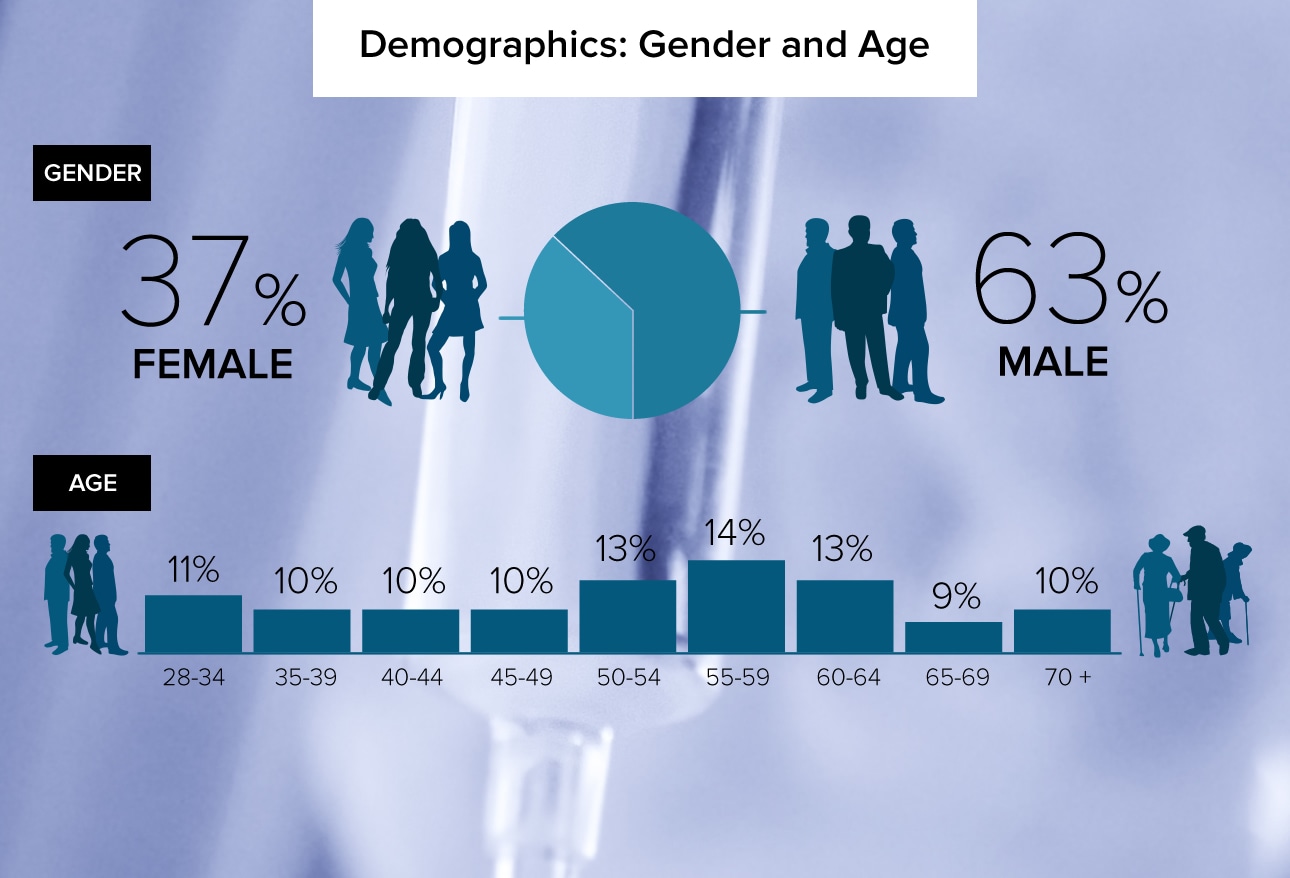

Physicians grapple with many wrenching decisions throughout their medical careers. Some situations involve whether to prolong or bring an end to patients' lives; others spark heated debates among physicians with different values. More than 21,000 physicians told Medscape how they feel about medicine's most critical issues. Respondents included more than 17,000 US and 4000 European physicians. This slideshow reports the US physicians' results. Representative respondent comments are also shown, to shed more light on the issues at hand.

Physicians grapple with many wrenching decisions throughout their medical careers. Some situations involve whether to prolong or bring an end to patients' lives; others spark heated debates among physicians with different values. More than 21,000 physicians told Medscape how they feel about medicine's most critical issues. Respondents included more than 17,000 US and 4000 European physicians. This slideshow reports the US physicians' results. Representative respondent comments are also shown, to shed more light on the issues at hand.

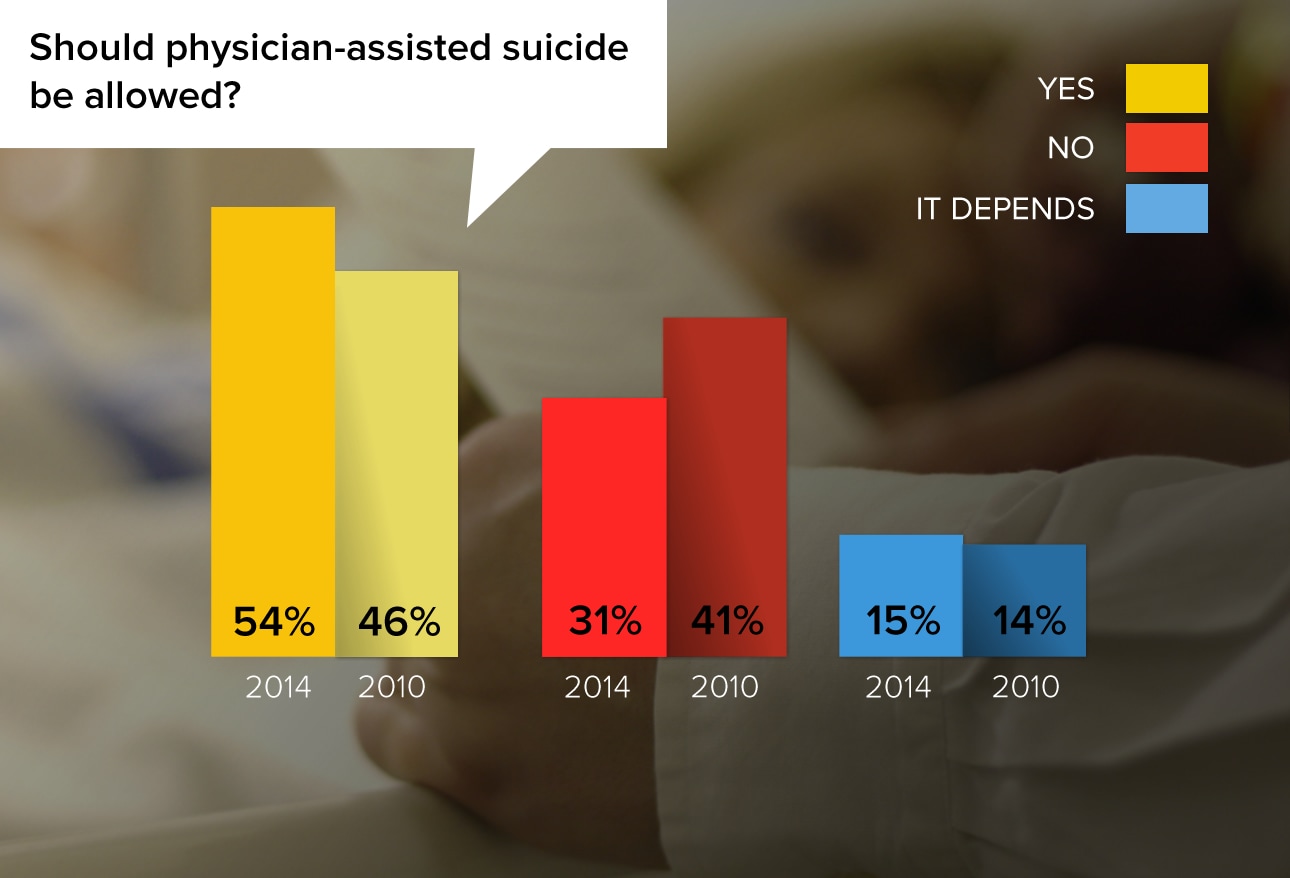

The subject of physician-assisted suicide has recently come to the forefront of public awareness, particularly in light of the death of 29-year-old Brittany Maynard, who chose to end her life in November 2014 as her terminal brain cancer progressed. Six US states have laws permitting physician-assisted suicide. Support for this measure has increased by 8 percentage points among physicians since Medscape first asked this question in the 2010 physician ethics survey.

"I believe terminal illnesses such as metastatic cancers or degenerative neurological diseases rob a human of his/her dignity. Provided there is no shred of doubt that the disease is incurable and terminal, I would support a patient's decision to end their life, and I would also wish the same option was available in my case should the need arise."

"Physicians are healers. We are not instruments of death. This is wrong."

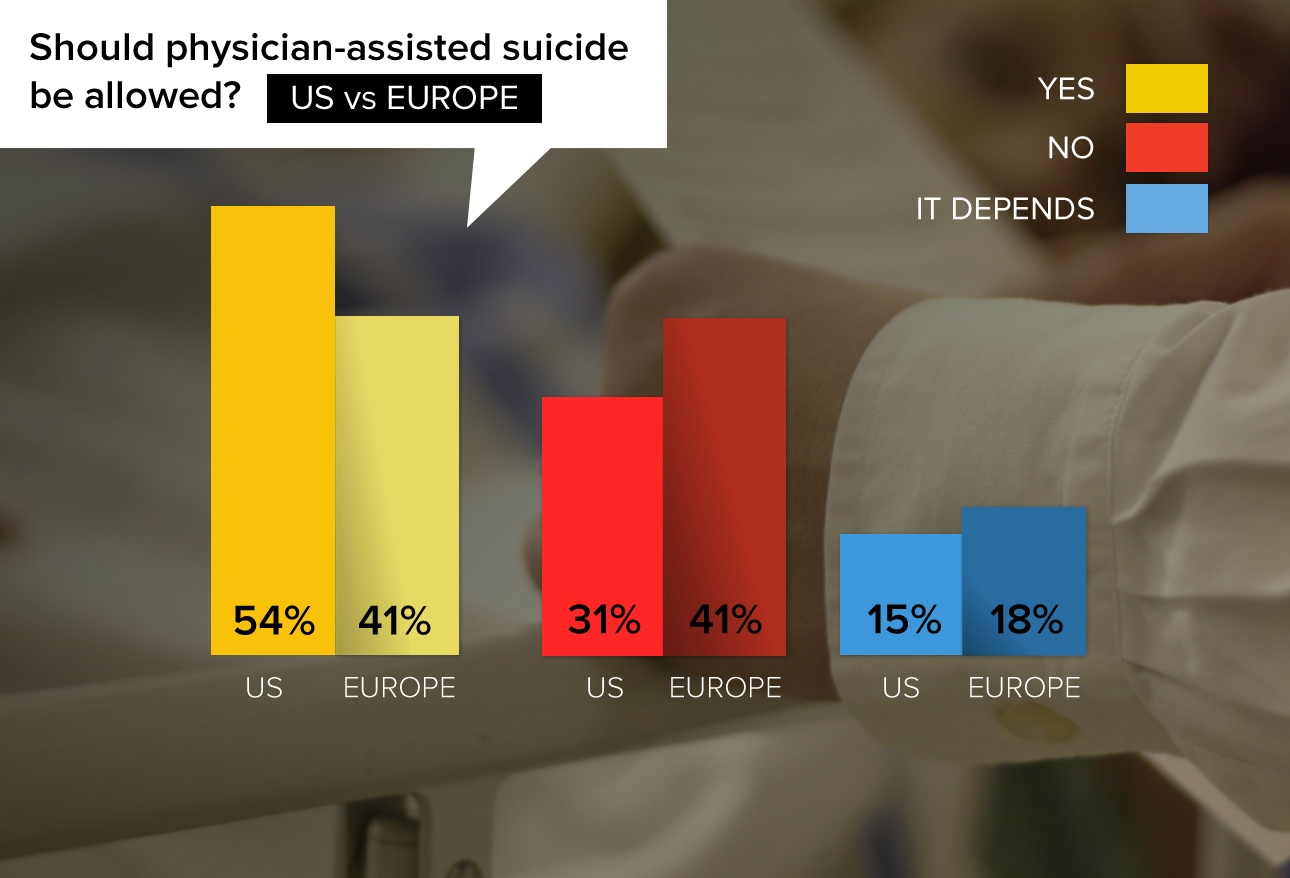

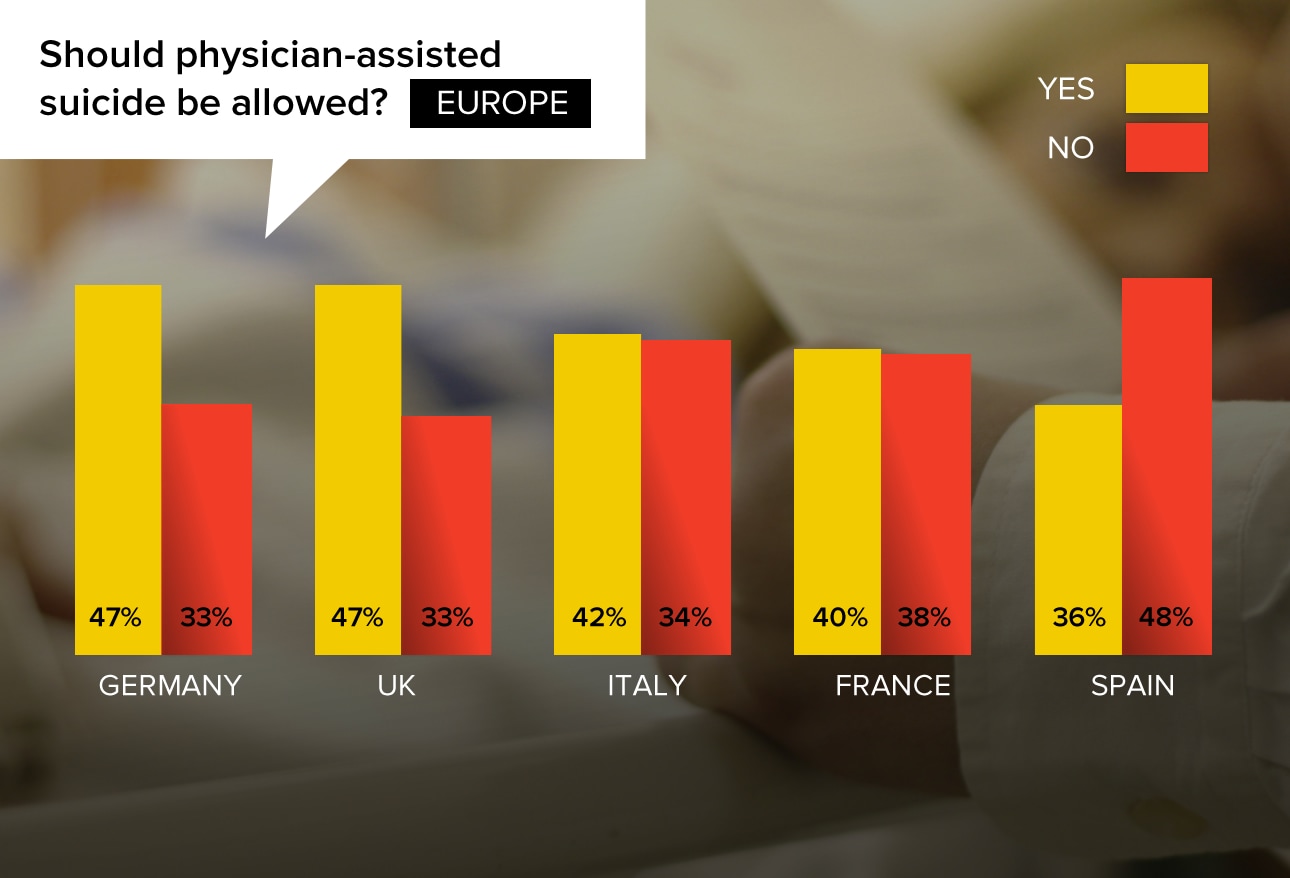

In the United Kingdom and several European countries, the concept is referred to as "physician-assisted dying." Attitudes about physician-assisted dying differ significantly from those of US physicians, related to different cultures, varying predominant religious values, and different views of the role of the physician. Almost 4000 doctors from more than 35 countries answered Medscape's ethics survey; the majority of respondents were from the United Kingdom, France, Italy, Spain, and Germany.

"Veterinarians do it all the time; it's a mercy we grant our pets. We should be able to give the same kindness to our (human) loved ones."

"MY JOB IS TO DO NO HARM. How does helping someone kill themselves make me any different from Dr Shipman (a British physician who murdered over 250 patients)?"

"There are clearly some situations (excruciating pain from terminal cancer, profound air hunger from ALS, etc.) where there should be leeway in humane terminal sedation."

Lord Falconer's Assisted Dying Bill is currently before the Parliament in England. Further discussion will take place at a date yet to be scheduled. A poll of 2050 adults in Great Britain in 2014 showed that 73% of respondents support the passage of an assisted dying law.1

Germany: "I would never assist in a suicide. But I think that there are a few patients who should be allowed to commit an assisted suicide."

United Kingdom: "Provided the whole family are in attendance and any one member could veto the procedure so that all are accessories to murder as the law stands at the moment."

Italy: "We have the right to make a choice of when to die. 'Physician-assisted dying' makes it easier for the patient."

France: "It is very difficult but, after eliminating depression and after multiple meetings, it is possible."

Spain: "Yes, when life extension involves unnecessary suffering for the patient."

1YouGov. Dignity in Dying survey results. http://d25d2506sfb94s.cloudfront.net/cumulus_uploads/document/63mety3ekh/

DignityinDying_Results_140521_AssistedDying.pdf

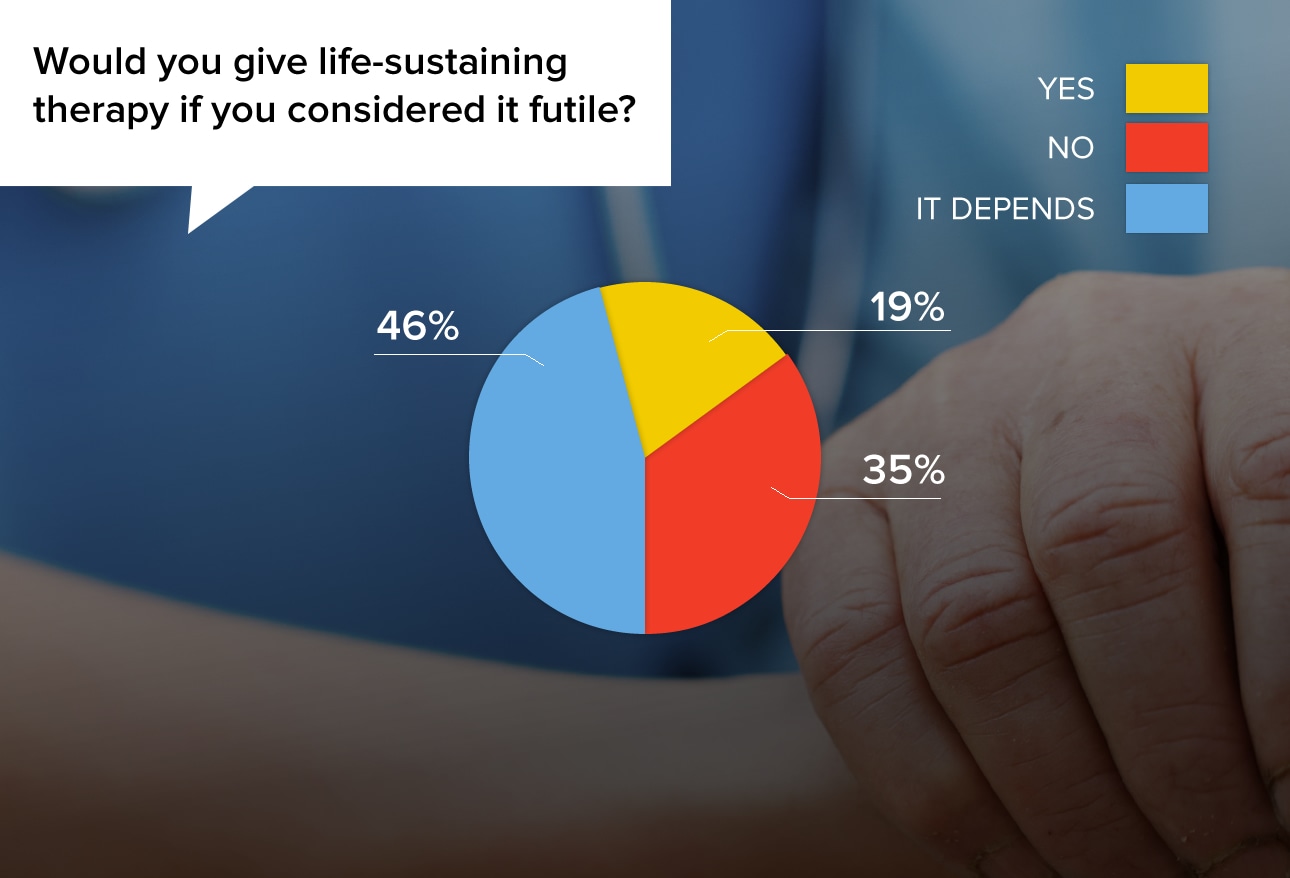

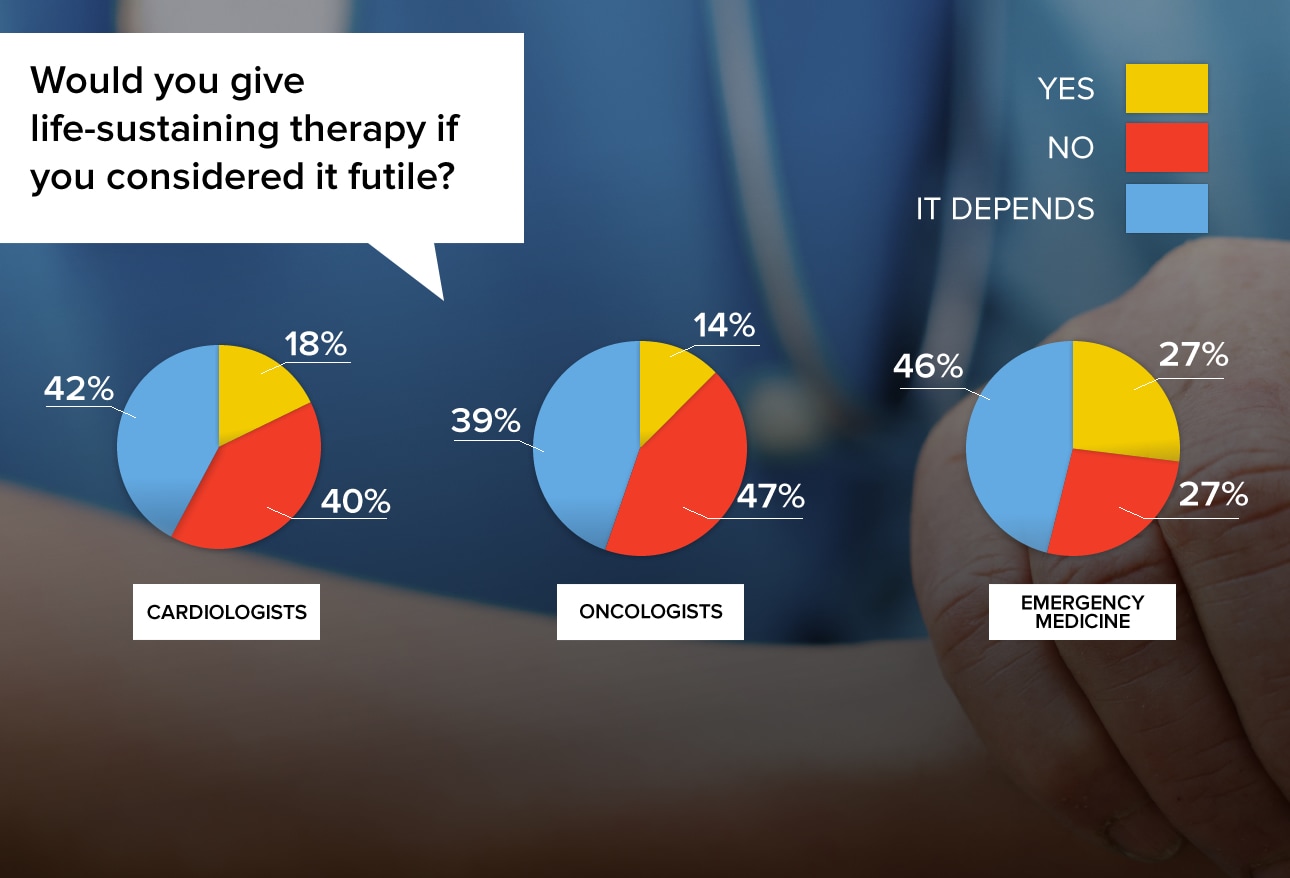

Thousands of physicians' written responses showed that empathy and concern for the patient's family plays a major part in their decision, as does giving the patient every reasonable chance to survive.

"Futile is a relative term! If the patient lives a few more months and his family can interact with him in a positive way, but he still dies of his disease, that is not futile."

"I would recommend or give life-sustaining therapy over a short period of time to allow the family members to accept the inevitable outcome and/or allow distant family members to come say their goodbyes."

"If it would make a family member feel better and know that everything that could be done, was done...I would recommend it."

"I have done so in the past, patient survived fatal liver failure and fully recovered. Miracles happen."

"This is not helpful for anyone, and is one of the reasons that healthcare costs are so high."

"Yes. CPR, for example, saves only a small proportion of those we administer it to (1-3%), but we employ it de facto in all cases of cardiac arrest whether or not the down time is known."

"I am an ER doc. If the patient has a pulse, nothing is futile unless there is an advanced directive or power of attorney to tell me otherwise."

"I never recommend life-sustaining therapy that I believe to be futile, or provide services when family refuses to withdraw care and wants ongoing treatment. It is very difficult."

"I would usually not recommend but would give if family or nursing care felt it was helpful."

"I will sometimes offer a short course (generally time limited) of aggressive therapy even if I expect it to be futile to help family members to feel confident that all was done in the care of their loved one."

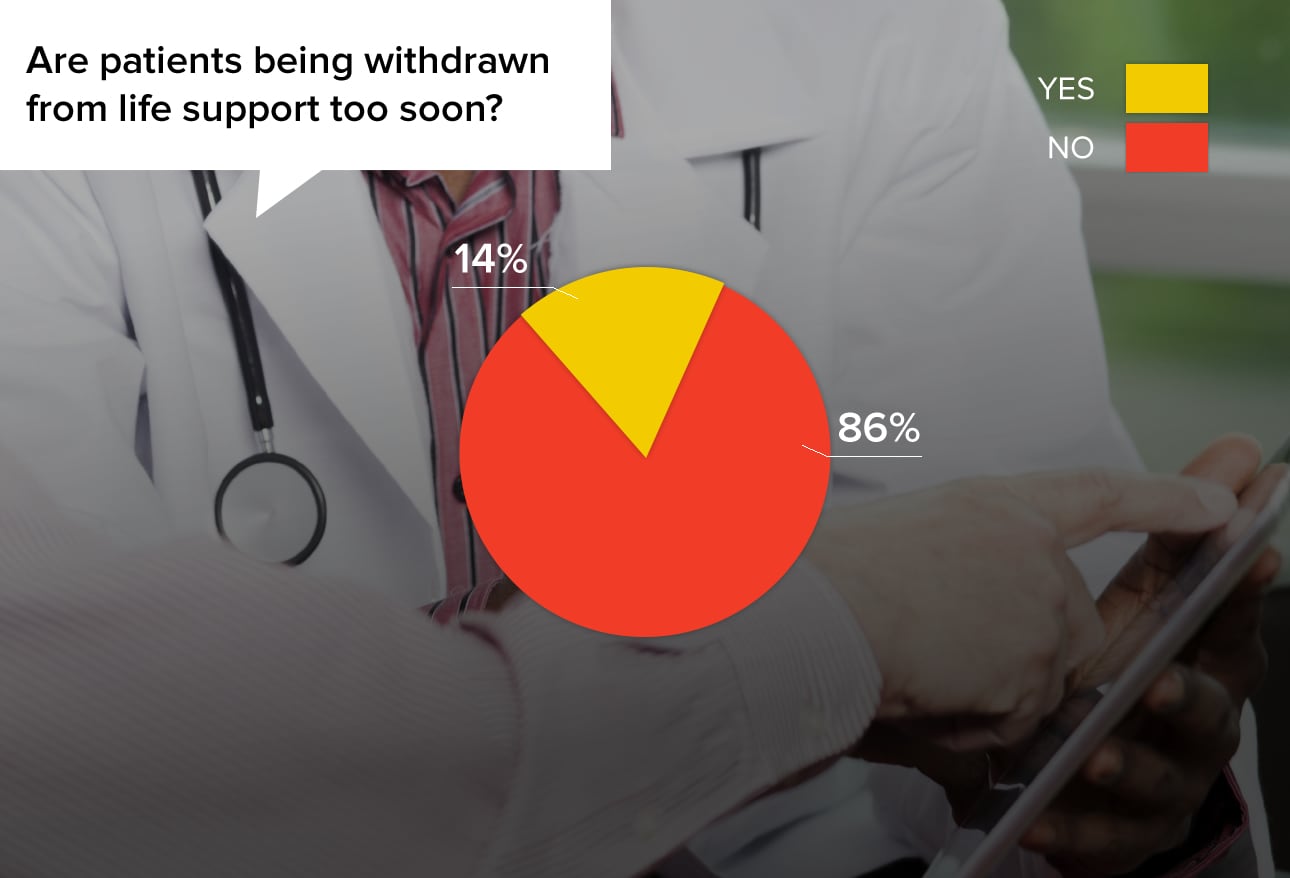

Many factors go into this decision, but in some cases, doctors claim that pressure has been exerted in order to save costs, either by the hospital or the family paying the bills.

"I think in some circumstances the push to remove the patient from life support is a little too aggressive. Sometimes the family needs a day extra to come to terms with removing life support."

"Remember, there's money in harvesting organs and in transplants also."

"I think the ethics committees are usually very thorough and able to justify their decisions if they follow the appropriate procedures."

"I've seen it if the patient's relatives know they will owe a lot of money."

"I think we tend to hold on too long and earlier withdrawal is appropriate."

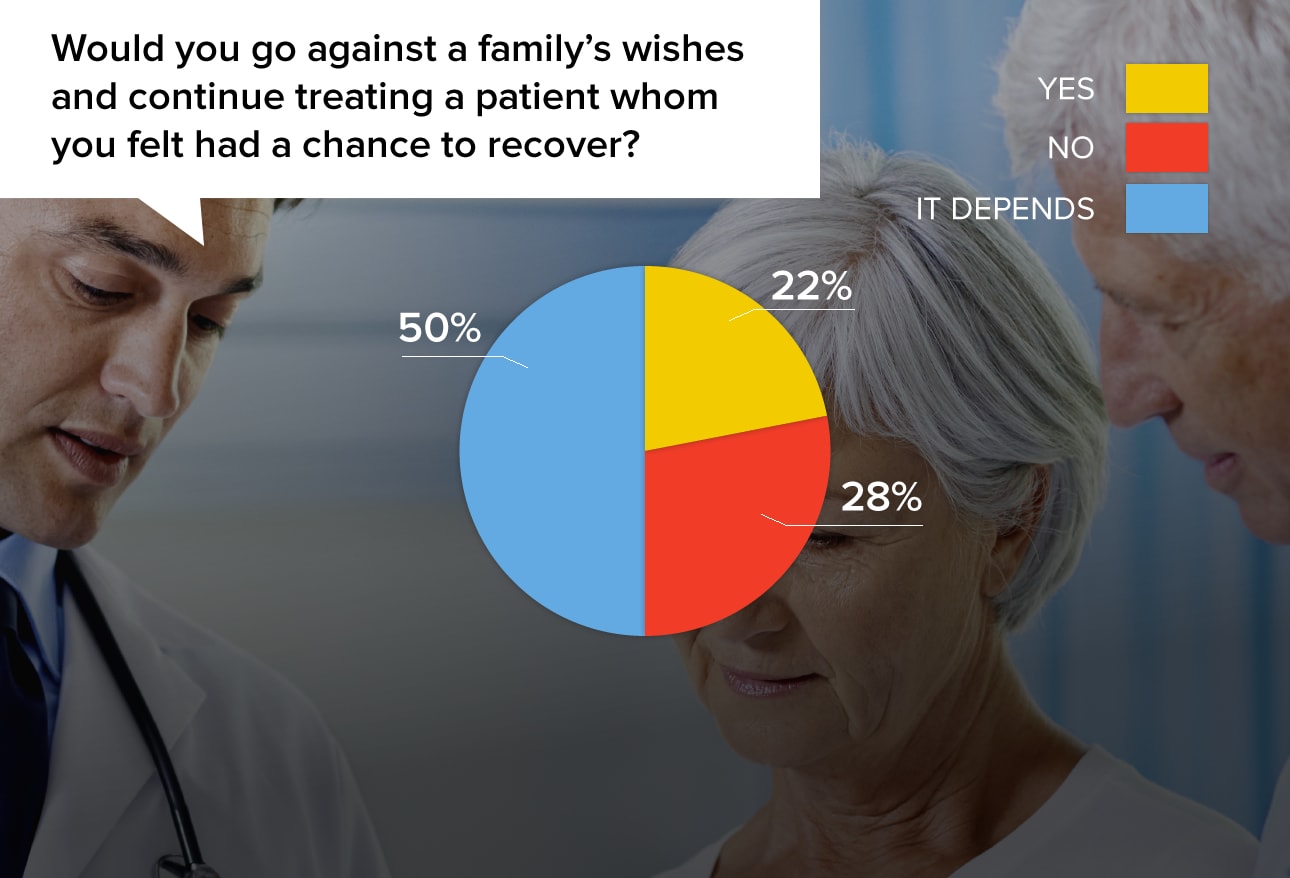

Conflict with a patient's family is not uncommon. Sometimes the legal right or power of attorney is on the family's side, so physicians may face an unpleasant battle if they feel strongly against the family's directives.

"My duty is to the patient, not an inheritor who may want to kill him off to get his estate."

"More than family's wishes are my beliefs about the chances of recovery for this patient."

"Yes, if the family's intentions were to end her life sooner for money or fortune, or other non-ethical reasons."

"I would explain to the patient and family the reasoning and allow them to choose another doctor if desired."

"I ask for understanding and permission to give me one to two days of continuing treatment to see what might happen."

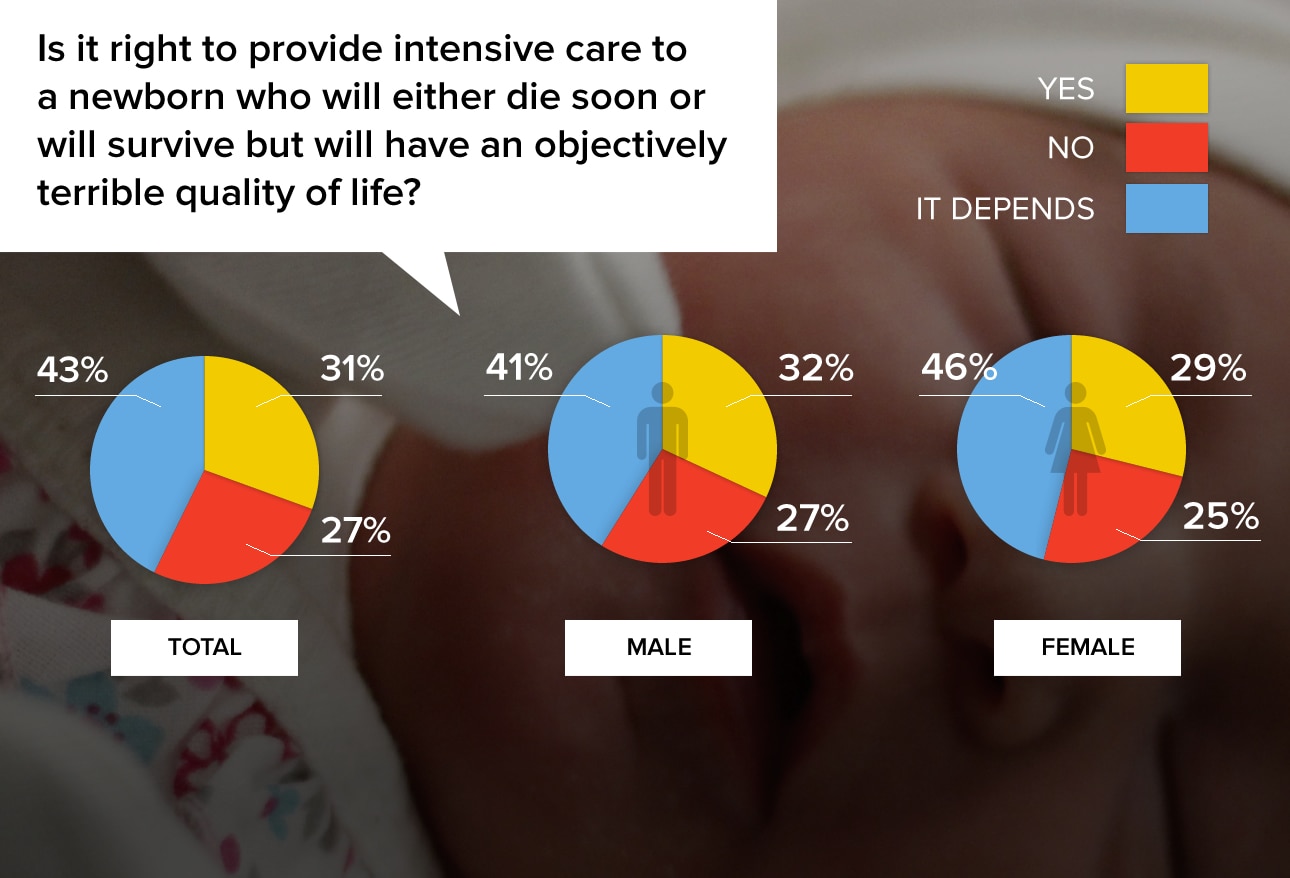

Physicians are almost evenly divided on this issue, and the judgment of "terrible life" varies widely. There was also little difference between male and female physicians.

"What, are we playing God now? How in the world do we know who will have a terrible life? There are many physically healthy people who are miserable and many physically challenged people who lead very meaningful lives."

"This is part of the nurturing that some parents who are losing a neonate NEED."

"I believe way too much money is spent on this...$$ which could be more usefully spent on pre-natal care and other prevention programs which would reduce the need."

"We are not allowed to torture children even at the request of their families."

"I can imagine a situation where all involved, not just the newborn, could be expected to have a terrible life. Then: no intensive care."

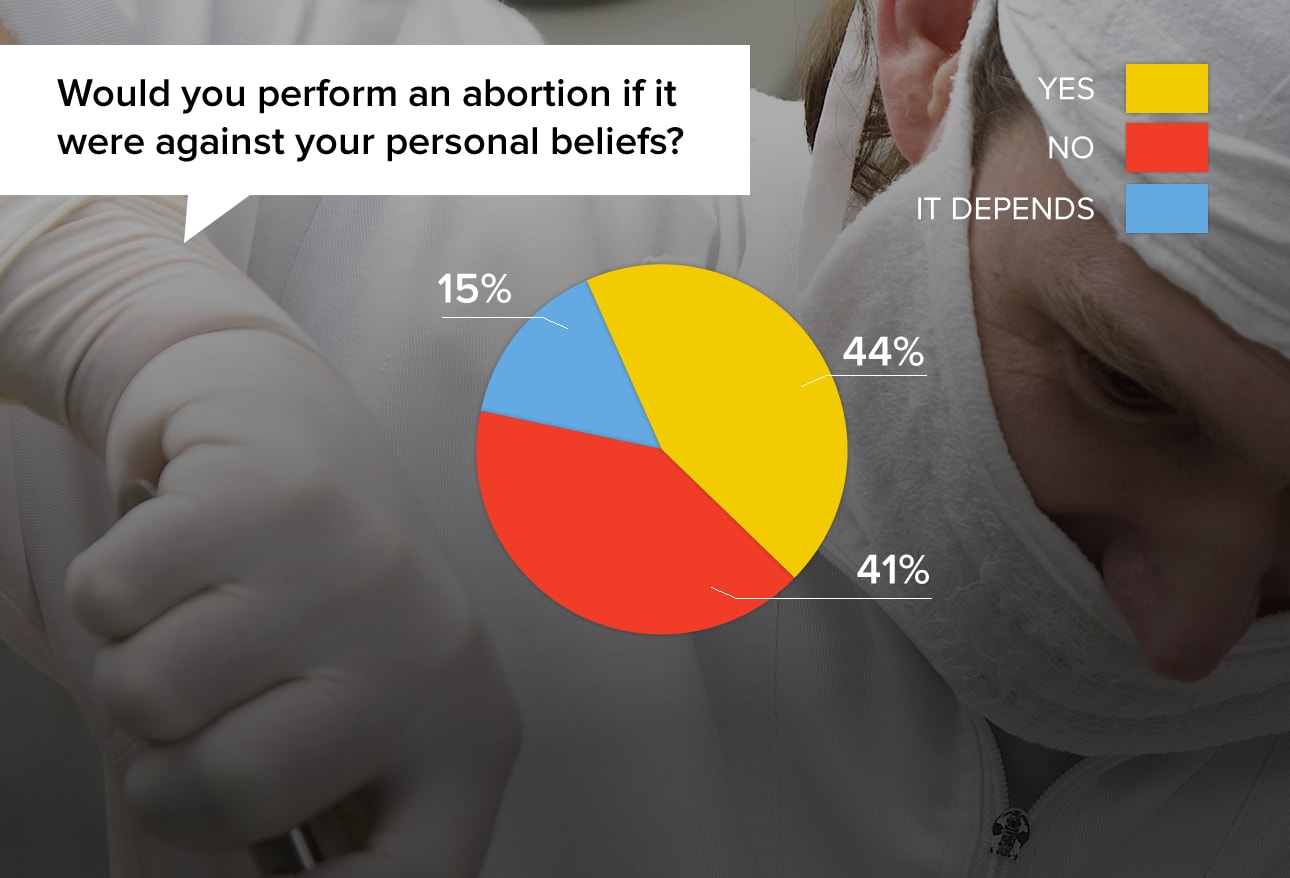

This hotly contested question revolves around two separate issues: a physician's beliefs about abortion, and whose rights or opinions are primary—the patient's or the physician's?

"My beliefs collide often with my clinical duty. But with the white coat on, the patient always comes first."

"NO. Abortions should be done for medical emergencies, not convenience. It is not a birth control measure."

"I would only do it if a dead fetus or dying fetus was severely compromising and risking the life of the mother."

"It is not my right to question others' beliefs. I assume that they hold their beliefs as strongly as I hold mine!"

"My religious beliefs should not be applied to others."

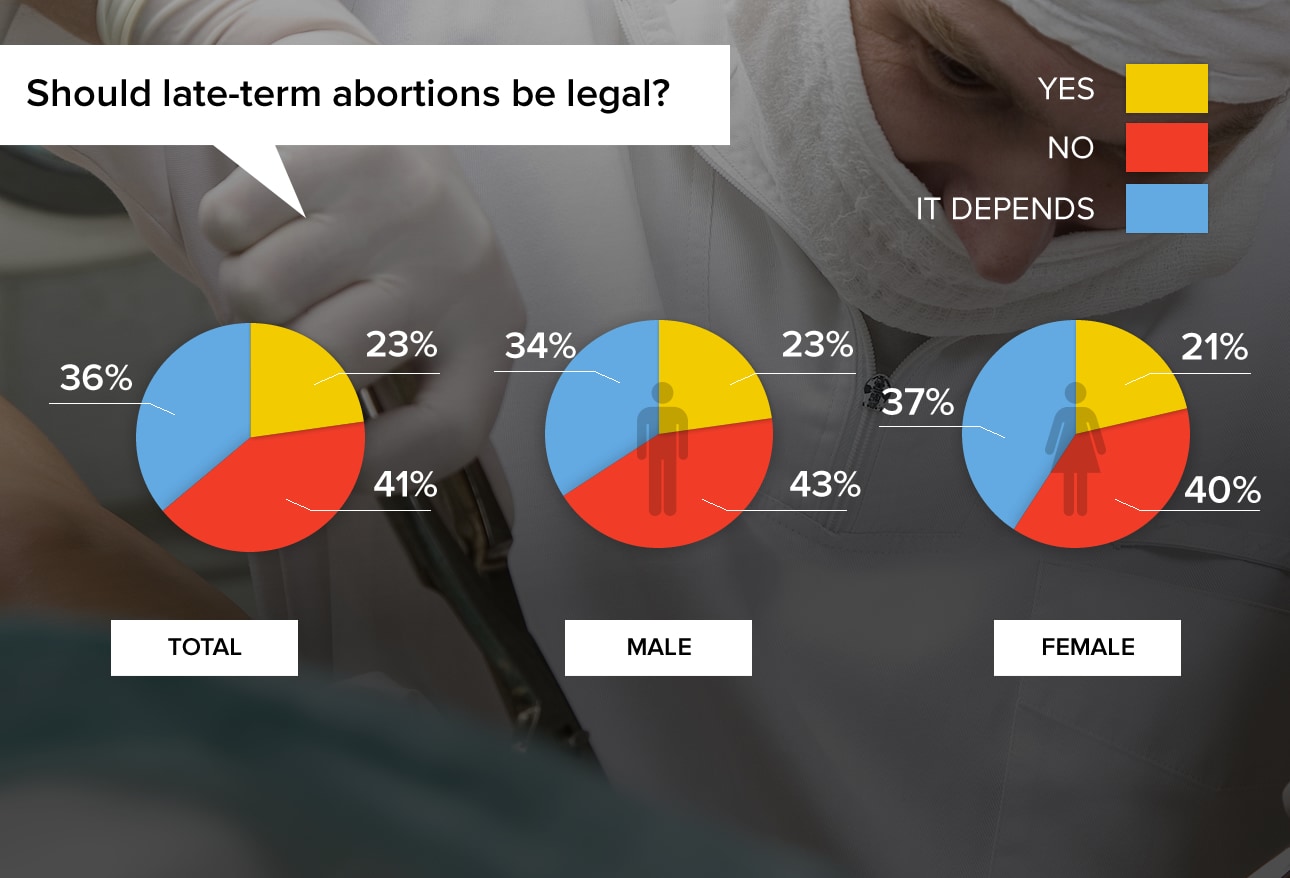

In the United States, 36 states have bans on late-term abortions (generally but not universally considered to be after 20 weeks), excluding situations that threaten a woman's life or health. In 2014, Florida enacted a bill that forbids an abortion if the fetus would be viable outside the womb, based on a physician's assessment.

"Physicians should promote the preservation of life."

"You might as well wait for the delivery and club the child to death."

"There are situations, although rare, where it can be the right decision—with certain anomalies (ex. anencephaly), or when there are significant medical defects for the child."

"As a pediatrician, I've seen too many tragedies to not know that it would have been better for all if the child hadn't been born."

"Only in cases beyond patient control. They may not find out about severe congenital anomalies until the 20-week ultrasound."

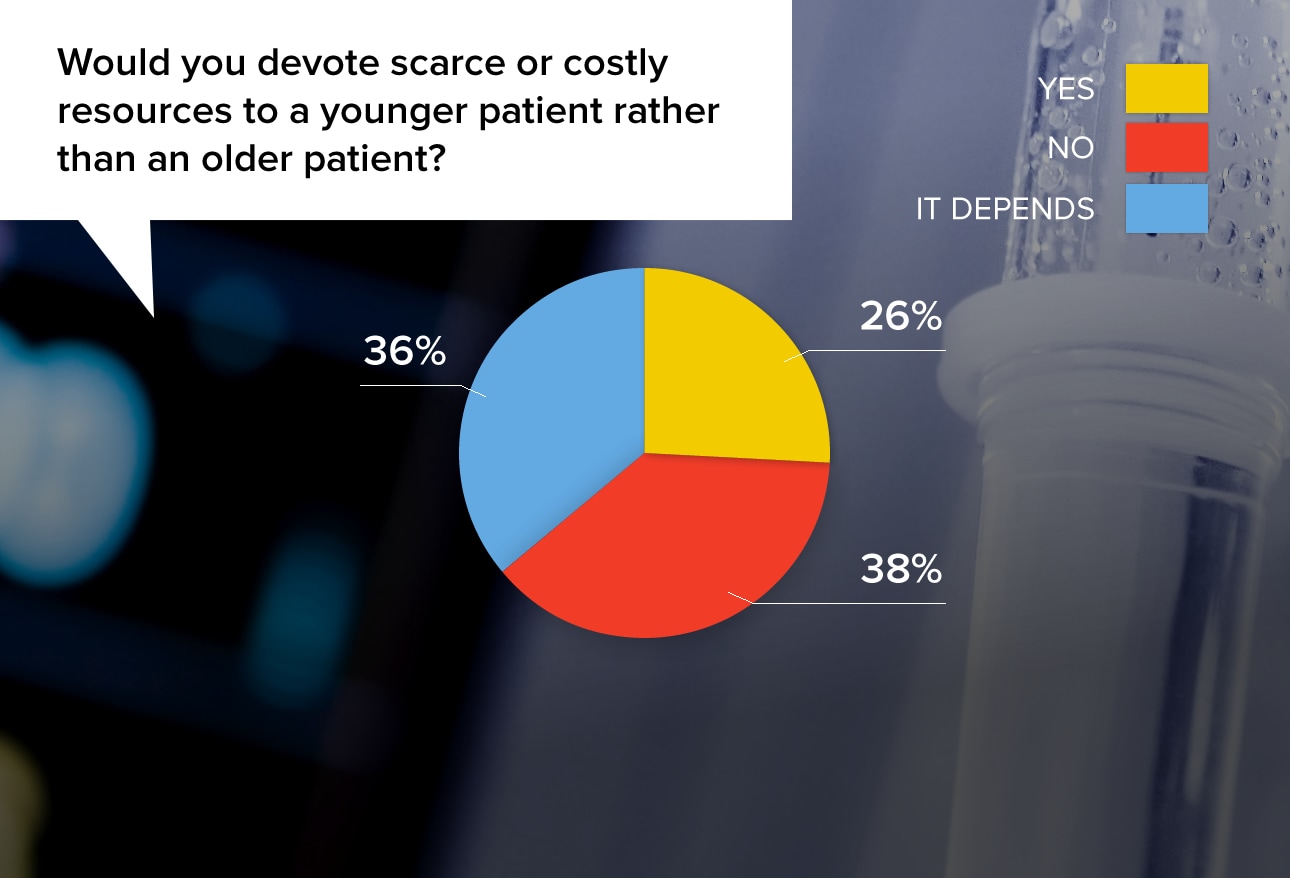

"Resources are limited. We should invest more on preserving life in younger patients, particularly if they have chances to survive."

"Ageism is morally right if there are limited resources and more years of life to be saved with the young patient."

"If the older person was someone like Steve Jobs, it is hard to decide that an unknown younger patient is more deserving."

"Absolutely, resources should be diverted to the young! And I'm a geriatrician. The young are the future. Sorry, but it's the truth."

"Specifics of the individual cases would need to be considered, not just age. What if the younger is a criminal and the older a retired teacher?"

1Emanuel E. Why I hope to die at 75. The Atlantic. September 2014.

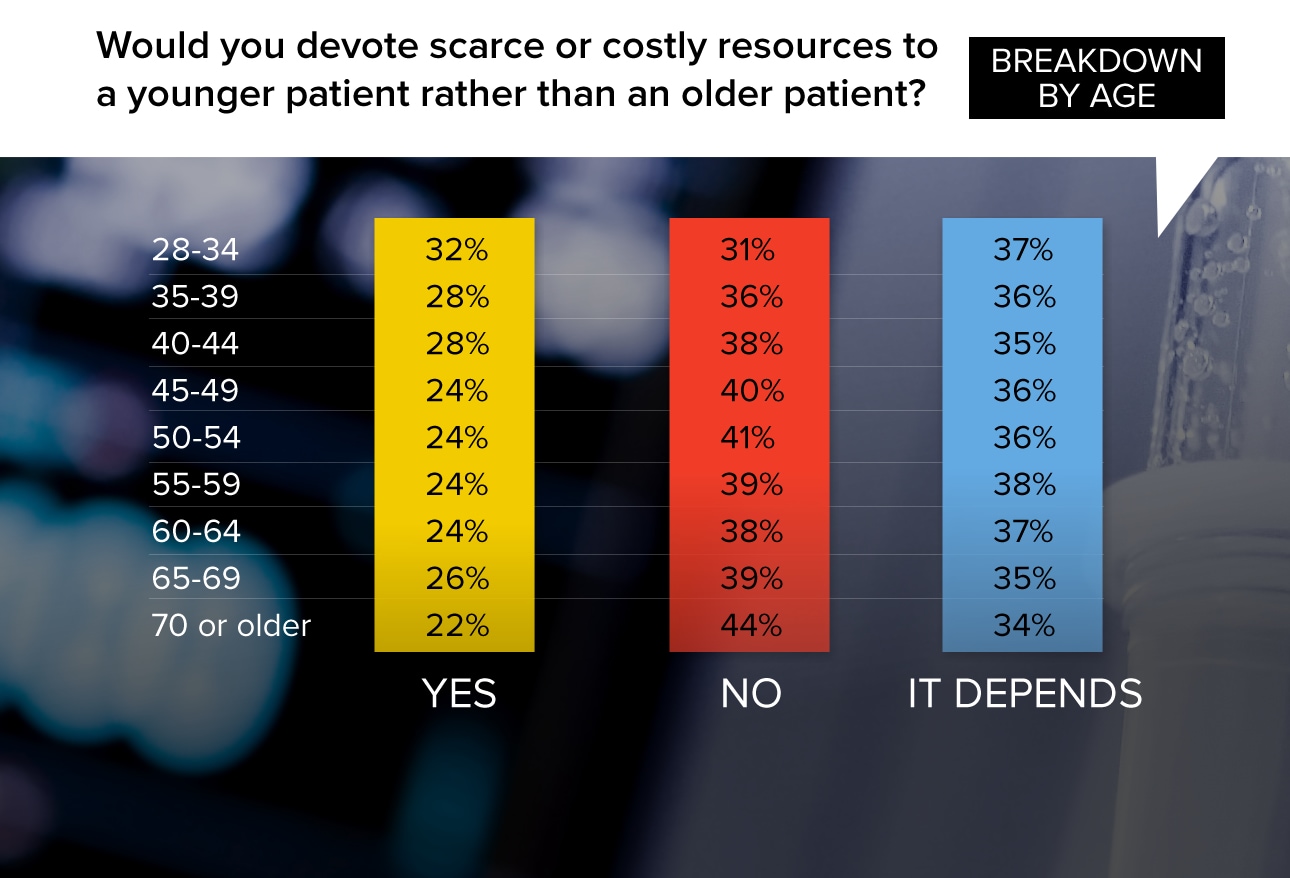

It's no surprise that the older one gets, the less likely he or she is to agree to reserving scarce resources for younger patients. In this survey, the percentage responding "yes" to this question declined from 32% in the youngest group of physicians to 22% in the oldest group.

"If you only had one of whatever you needed, and both patients had need — I would give it to the younger, most likely."

"I think life expectancy is a major factor to any diagnostic or therapeutic decision."

"Ages are important. Would I give a liver transplant to a 13-year-old before a healthy 80-year-old? Absolutely. A 13-year-old vs a 40-year-old father of three kids? NO."

"Yes. The younger person has a better chance of living and becoming fruitful and providing for the community as a whole. The older person might have lived a life that was already fruitful. But either way, the older person has passed their time for making lasting contribution to society."

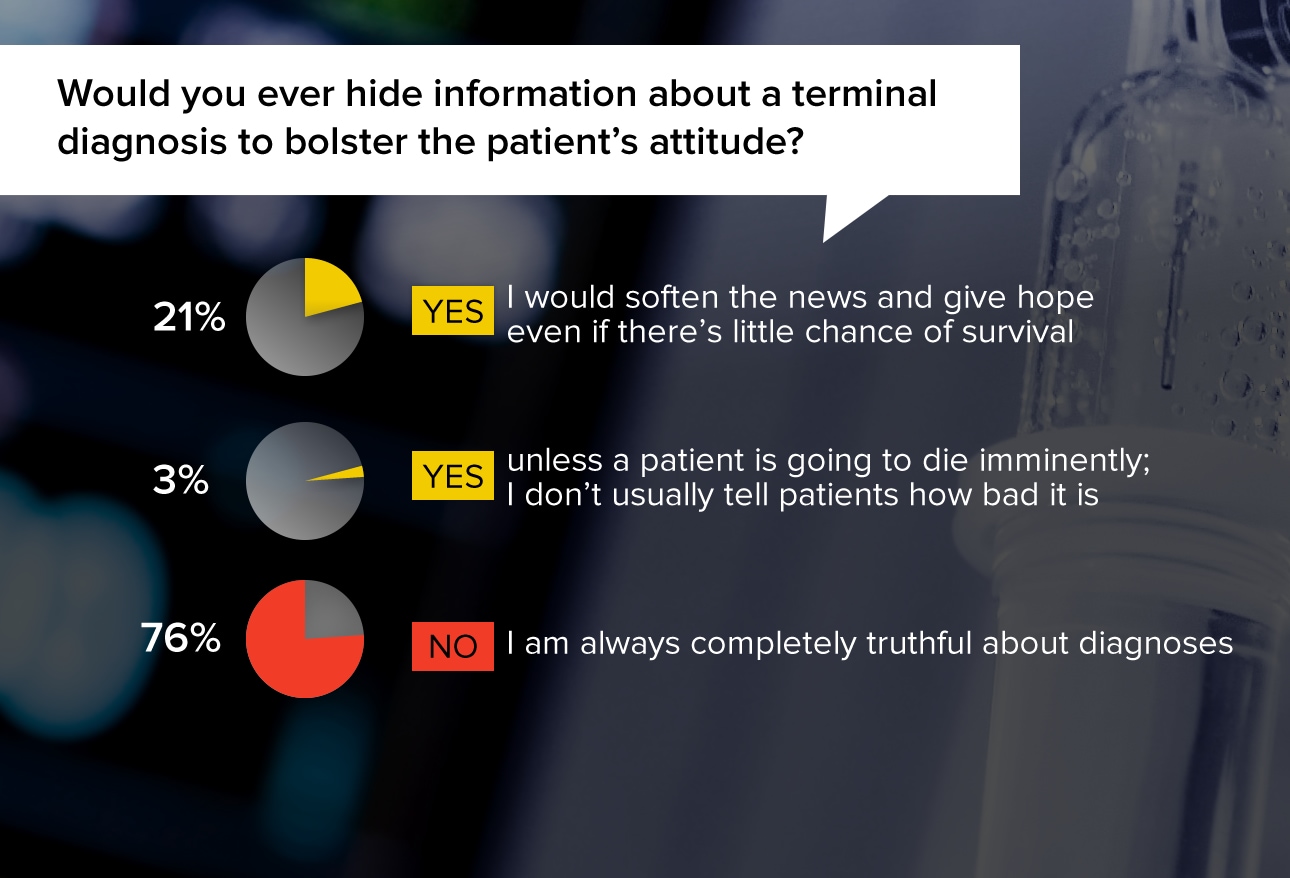

Honesty is valued in ethical medical treatment, and there's no doubt that legal threat is part of the equation. But many doctors also feel that a patient's positive attitude can help his physical condition, and grim news could destroy hope.

"I would not want to remove hope or the will to live."

"If the patient is already demoralized and suffering, I might not tell them it's hopeless, although I wouldn't lie if they asked."

"Sometimes news like that can kill the patient sooner than the disease because they stop fighting. Doctors are not gods and miracles do happen. I have seen them happen, so I truly believe that there is always hope."

"People need to know so they can plan and prepare. It should be done very honestly but with the most empathy and support possible."

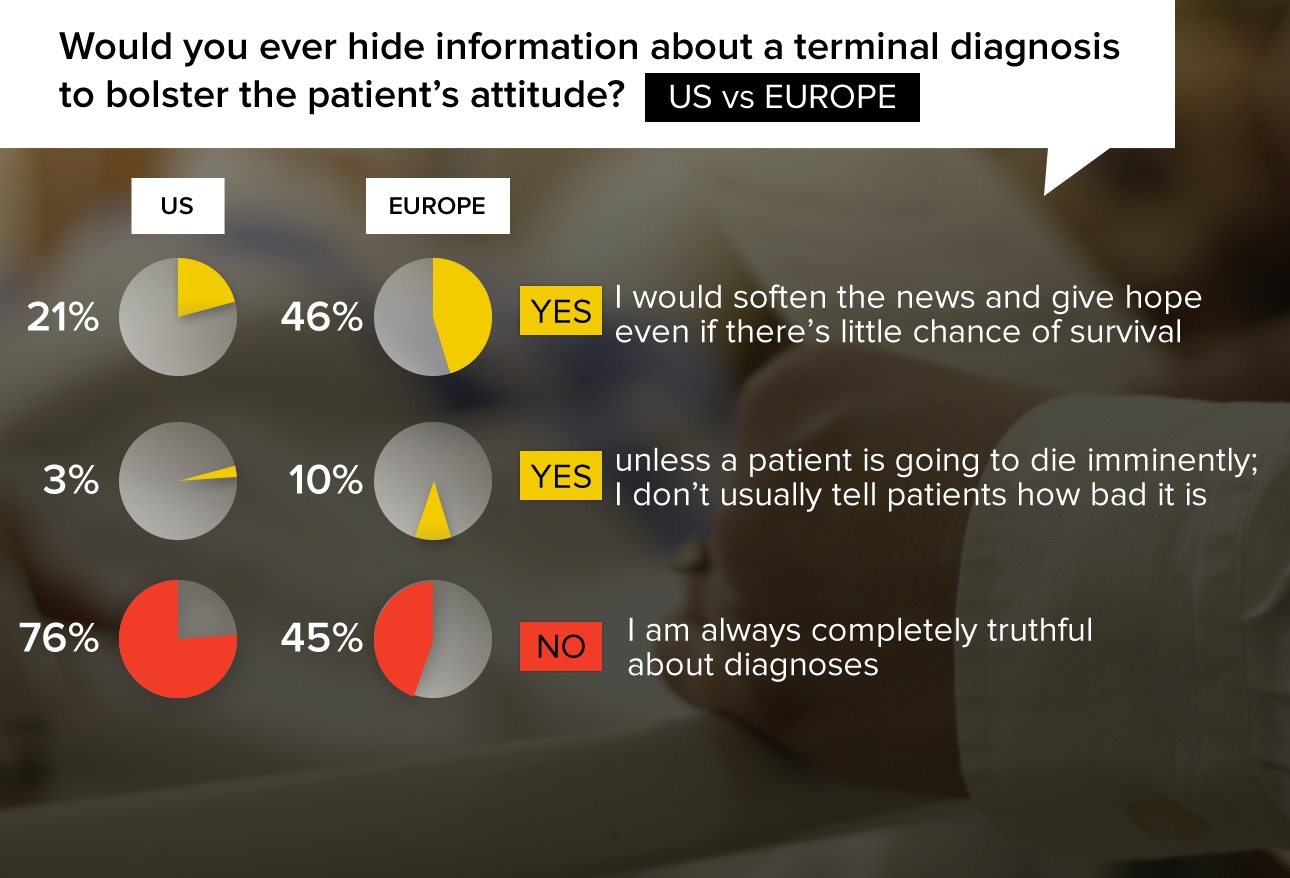

There is a notable difference in the way this issue is treated in the United States vs in Europe. Only 24% of US physicians gave a "yes" response, compared with 56% of European physicians. It has been suggested that a more paternalistic doctor-patient relationship exists among Europeans, and that the malpractice climate in the US is also a factor.

"I think patients should always have hope for something better. Even if there is little hope theoretically, a doctor can never be God himself."

"No diagnosis is 100% correct. I would always try to leave room for a little hope. Softening the news is not hiding information."

"It is important to be honest but it is also important to support and offer hope. All of us have been wrong about cancer prognosis at some time."

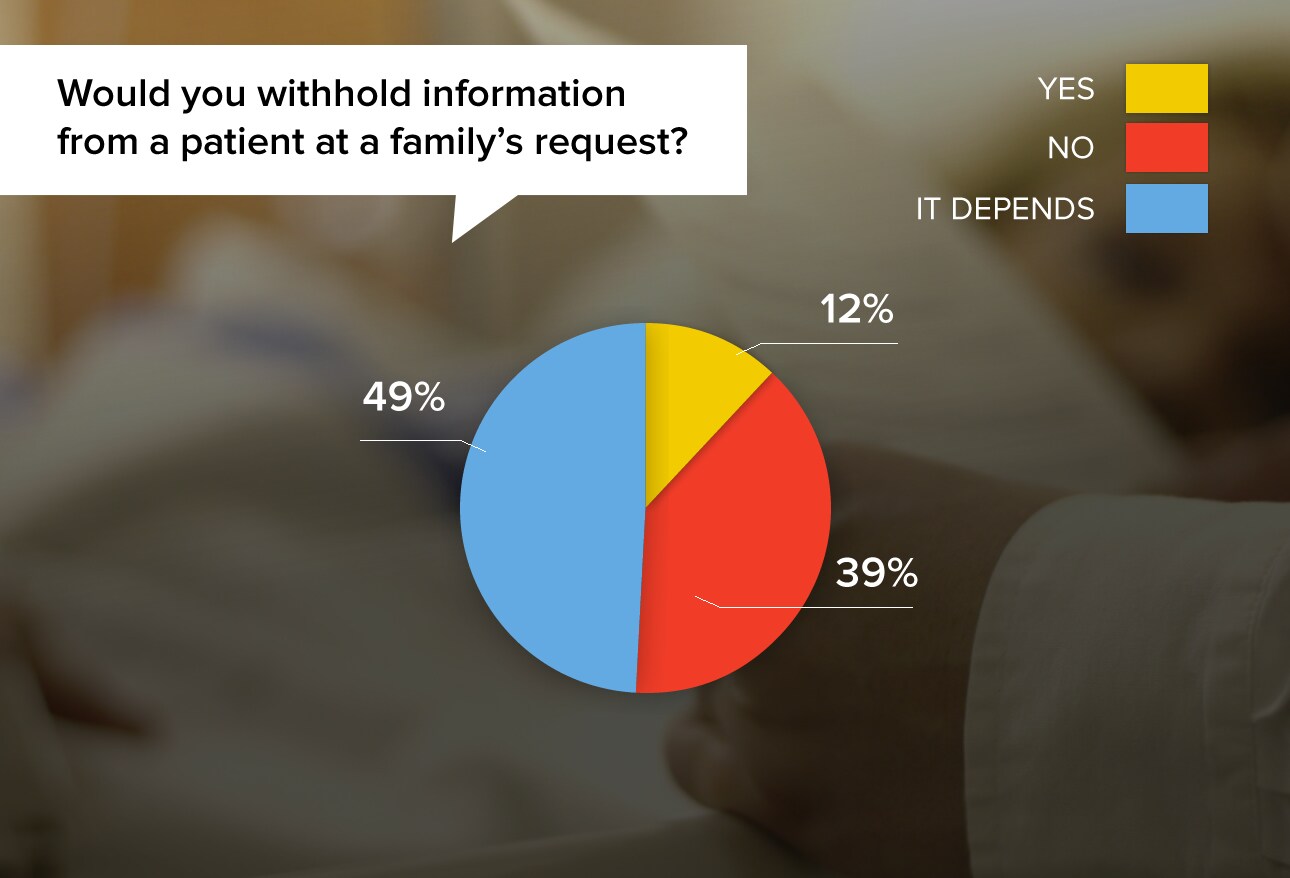

Physicians are occasionally asked to withhold information from a patient, for various reasons. Sometimes the request makes sense, but physicians also say that sometimes they are troubled by the family's motives or decision.

"If the patient's illness causes impairment of judgment and the family member has been given durable power of attorney for healthcare by the patient, then yes."

"Many patients have limited cognition. The family's preferences take precedence. The family still gets the whole story."

"In geriatric populations, it is better to have them in positive spirits, particularly if they are terminally ill."

"Yes, but I always write the information down and I tell that to the patient.”

"I will try my best to find a way and time when I can reveal the information, especially to an adult patient. In certain complex circumstances it may be necessary to withhold information for some time."

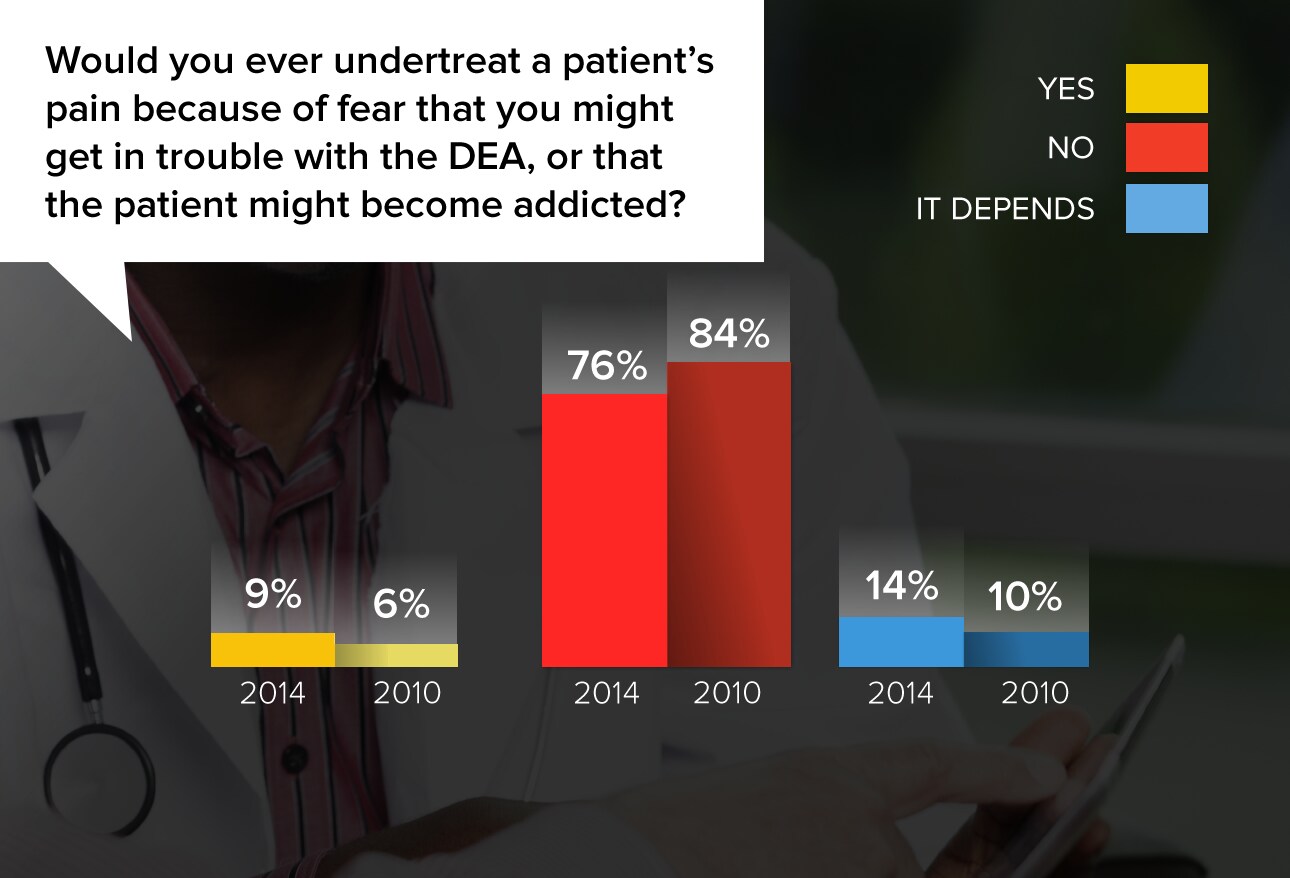

Physicians were adamant in their resolve to put patients' welfare first when it comes to pain alleviation, but they were also clear that they considered the DEA a formidable and perhaps capricious force, whose attention was to be avoided at all costs.

"Sorry, I'm afraid of these folks and don't want to go to jail."

"No, the people deserve to have their pain treated as best as you can."

"Yes. I would not want to break any laws in regard to prescribing opiates, and if the DEA makes a law I would have to follow it, even if the patient suffers."

"I would do what's best for the patient and not consider the DEA."

"It sucks to be in pain, but that is still not a life-threatening issue. The DEA, however, is career-threatening if they think you are not prescribing opiates appropriately."

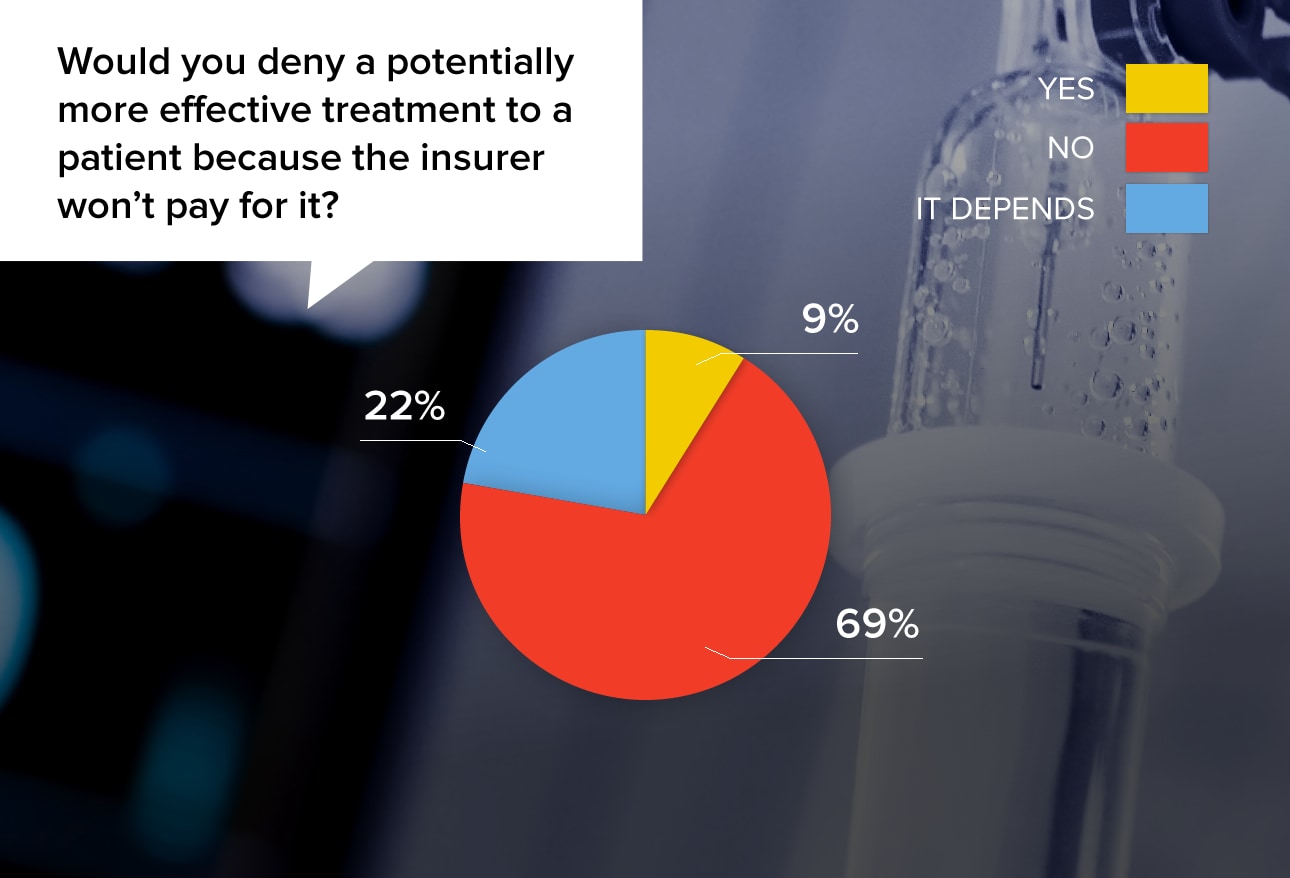

While the majority (69%) of physicians said they would not deny treatment in this circumstance, most admitted in their comments that the situation is difficult and that the realities of payment had to be considered.

"This happens every day, right? Patients do not get treatments they cannot pay for."

"In hospice we have to make this judgment all the time. Potentially palliative interventions have to be balanced against the reimbursement provided under the Medicare Hospice Benefit."

"If they did not want to pay out of pocket and insurance denied it, I would not provide it. They could look into alternative means of payment, and if something could be arranged, then I would proceed with treatment."

"I am not in a position to pay for someone else's medical care."

"I would have them fight their insurance company and help tell them what to do, but I could not pay for it. I am barely surviving these days."

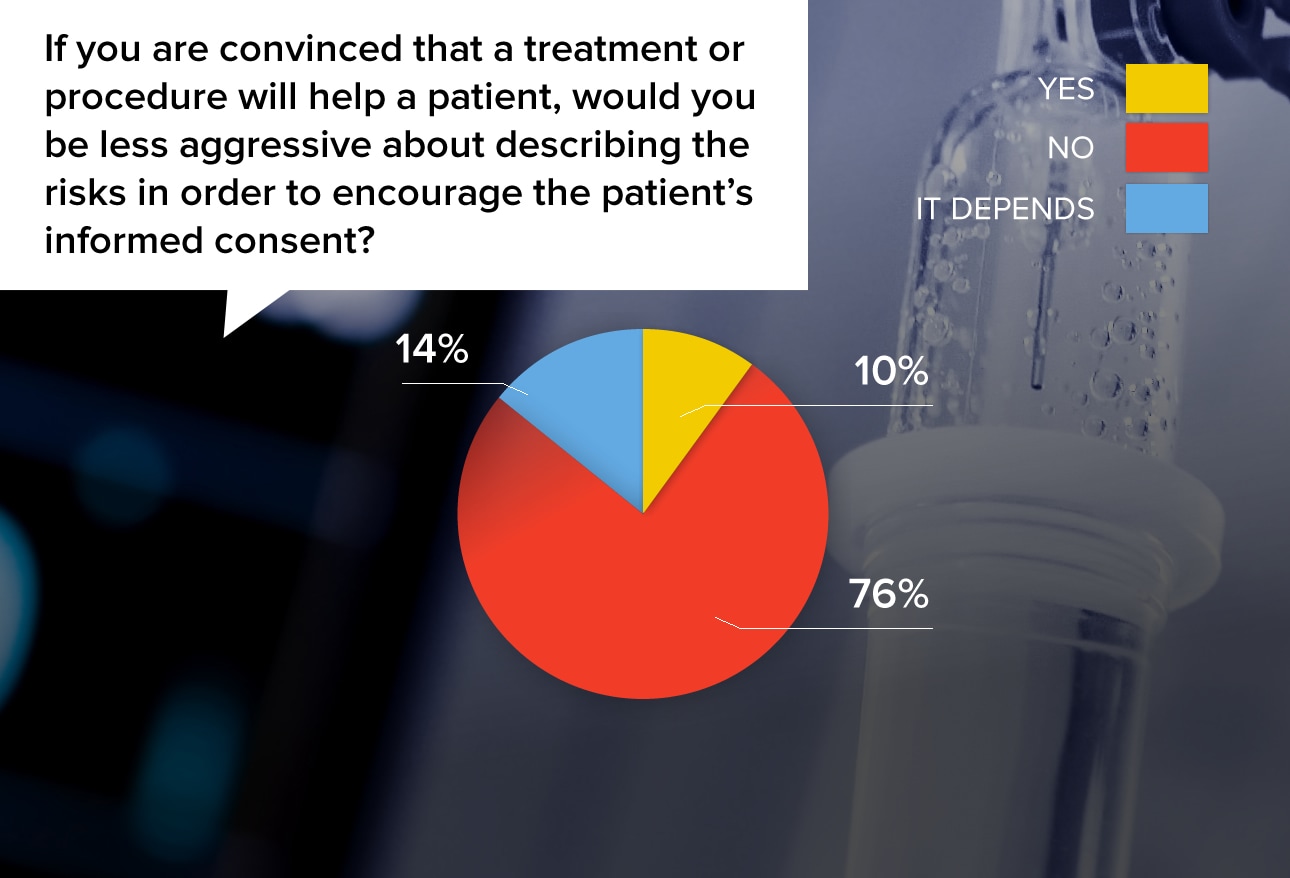

It's been said that if a physician described every potential risk of a treatment, no patient would ever have any medical care. Doctors make choices about how to convey the risks and benefits of a treatment, and these choices vary by physician.

"Being aggressive about describing the risk will definitely make the patient worried about the operation and have second thoughts about having it."

"The patient trusts me to guide them toward their best clinical option. Therefore, less valuable alternatives will be painted with the blacker brush."

"I wouldn't lie or withhold risks, but patients want me to recommend as well as explain options. That requires me to explain why one is better than the other, which involves minimizing risks."

"They need to know the risks. If something goes bad and they later found out that you did not tell them, then the 1-800 Bad Drug lawyer is called."

A majority of physicians could name at least one ethical dilemma that they remembered years later. Many of them noted that the situation still bothered them, and that they wished they had acted differently. Others felt that they had done the right thing, despite substantial fallout.

"My grandfather's euthanasia request that he made to me: I did not comply."

"Treating pain in a patient who could not communicate. The family did not want to give pain meds, but the physicians all felt that the patient was in pain."

"Having a patient on life support for close to a year, in a vegetative state, with the family unwilling to withdraw care."

"A family did not want their father to know about his cancer diagnosis. The cancer was treatable, but aggressive, and the family did not want to pursue it because they were afraid of how the father would tolerate it."

Medscape Ethics Report 2014, Part 2: Money, Romance, and Patients

Medscape Ethics Report 2014, Part 2: Money, Romance, and Patients What Do You Think About Physician Ethics?

What Do You Think About Physician Ethics? Medscape Employed Doctors Report: Are They Better Off?

Medscape Employed Doctors Report: Are They Better Off? Residents Salary & Debt Report 2014

Residents Salary & Debt Report 2014 Medscape EHR Report 2014

Medscape EHR Report 2014 Best & Worst Places to Practice 2014

Best & Worst Places to Practice 2014