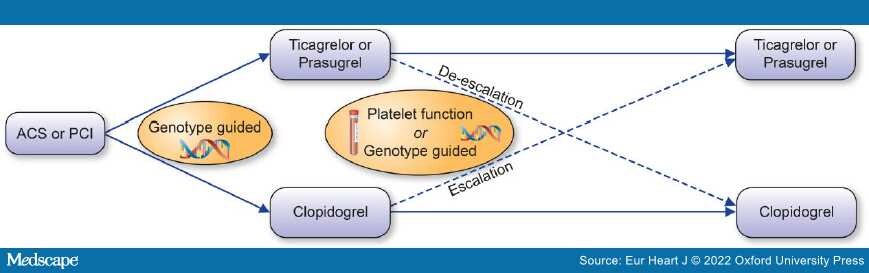

Graphical Abstract: A guided approach to escalation or de-escalation of antiplatelet therapy.

As we evolve toward an era of more personalized medicine, there exists appeal for a tailored approach toward antiplatelet therapy. It has long been known that there is significant interpatient variability in response to clopidogrel. Following a 300 mg loading dose of clopidogrel, ~30% of individuals are observed to have an attenuated pharmacodynamic response as assessed by platelet function testing.[1] A fraction of the variability in response to clopidogrel appears to be explained by genetic inheritance of a reduced function CYP2C19 allele,[2] a genetic variant that encodes an enzyme that is involved in both steps of the drug's bioconversion to its active metabolite. Carriers of a reduced function CYP2C19 allele have diminished pharmacodynamic and kinetic response to clopidogrel and are at increased risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) and stent thrombosis in the setting of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).[3]In response to these findings, the United States Food & Drug Administration applied a warning to the package insert for clopidogrel to make clinicians aware that some individuals are poor metabolizers of the drug and noted that use of an alternative treatment strategy should be considered in this setting.