Acne remains the commonest chronic inflammatory dermatosis, affecting up to 96% of adolescents.[1] Prevalence data suggest acne is presenting earlier and persisting longer.[2] The negative impact of acne can be profound, and it ranks globally as one of the most burdensome skin conditions.[3] High-quality, evidence-based guidelines that are practical, relevant, easily accessible and understood by all stakeholders are key to sharing the latest knowledge and implementing effective management. Existing acne guidelines have been shown to have limitations.[4] Acne guidelines are challenged both by a paucity of trials comparing treatments, and nonstandardized approaches for assessment.[5]

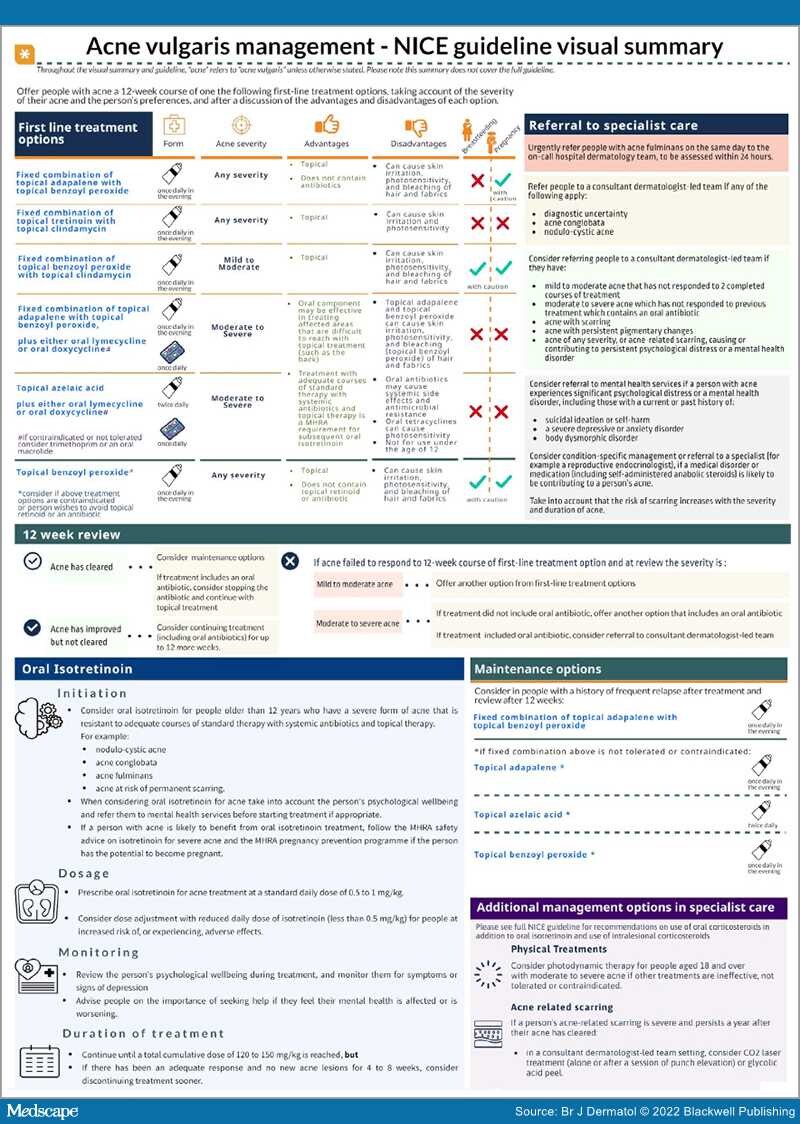

Recently, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) launched a novel acne guideline informed by robust analyses of the evidence, addressing areas previously lacking from guideline quality appraisals.[6] It provides practical considerations for clinicians, which should optimize management and guide primary care clinicians on when to refer to dermatologists. Further, it identifies important areas that lack evidence, to inform recommendations and future research. Many of these areas align with those identified in the James Lind Alliance Acne Priority Setting Partnership,[7] emphasizing the need to invest in research for this common condition. A visual summary of the guideline is featured in Figure 1.