Abstract and Introduction

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has magnified longstanding health care and social inequities, resulting in disproportionately high COVID-19–associated illness and death among members of racial and ethnic minority groups.[1] Equitable use of effective medications[2] could reduce disparities in these severe outcomes.[3] Monoclonal antibody (mAb) therapies against SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, initially received Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in November 2020. mAbs are typically administered in an outpatient setting via intravenous infusion or subcutaneous injection and can prevent progression of COVID-19 if given after a positive SARS-CoV-2 test result or for postexposure prophylaxis in patients at high risk for severe illness.† Dexamethasone, a commonly used steroid, and remdesivir, an antiviral drug that received EUA from FDA in May 2020, are used in inpatient settings and help prevent COVID-19 progression§.[2] No large-scale studies have yet examined the use of mAb by race and ethnicity. Using COVID-19 patient electronic health record data from 41 U.S. health care systems that participated in the PCORnet, the National Patient-Centered Clinical Research Network,¶ this study assessed receipt of medications for COVID-19 treatment by race (White, Black, Asian, and Other races [including American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, and multiple or Other races]) and ethnicity (Hispanic or non-Hispanic). Relative disparities in mAb** treatment among all patients†† (805,276) with a positive SARS-CoV-2 test result and in dexamethasone and remdesivir treatment among inpatients§§ (120,204) with a positive SARS-CoV-2 test result were calculated. Among all patients with positive SARS-CoV-2 test results, the overall use of mAb was infrequent, with mean monthly use at 4% or less for all racial and ethnic groups. Hispanic patients received mAb 58% less often than did non-Hispanic patients, and Black, Asian, or Other race patients received mAb 22%, 48%, and 47% less often, respectively, than did White patients during November 2020–August 2021. Among inpatients, disparities were different and of lesser magnitude: Hispanic inpatients received dexamethasone 6% less often than did non-Hispanic inpatients, and Black inpatients received remdesivir 9% more often than did White inpatients. Vaccines and preventive measures are the best defense against infection; use of COVID-19 medications postexposure or postinfection can reduce morbidity and mortality and relieve strain on hospitals but are not a substitute for COVID-19 vaccination. Public health policies and programs centered around the specific needs of communities can promote health equity.[4] Equitable receipt of outpatient treatments, such as mAb and antiviral medications, and implementation of prevention practices are essential to reducing existing racial and ethnic inequities in severe COVID-19–associated illness and death.

The PCORnet-distributed data infrastructure was queried,¶¶ and 41 sites*** returned data on monthly receipt of medications for COVID-19 treatment during March 2020–August 2021. The monthly percentage of patients with a positive SARS-CoV-2 test result who received mAb (November 2020–August 2021) and of inpatients with a SARS-CoV-2 positive test result who received dexamethasone or remdesivir (March 2020–August 2021) was calculated separately by race and by ethnicity (as aggregated in PCORnet) for adults aged ≥20 years. Differences in treatment by race and ethnicity were assessed in two ways. First, pairwise Wilcoxon signed rank tests, with p-values indicated as pw, were used to assess whether treatment receipt differed systematically over time (systematic temporal differences) by race or ethnicity. Second, relative monthly treatment disparities were calculated as the difference in percentage of patients treated between racial or ethnic minority (Black, Asian, Other for race; Hispanic ethnicity) and majority (White; non-Hispanic) groups divided by the percentage treated in the majority groups for each month.††† The grand means (means of relative monthly treatment disparities) were calculated, and t-tests for statistical difference from zero, with p-values indicated as pt, were used to assess presence of overall relative treatment disparities. Results were considered statistically significant for p-values <0.05. GraphPad Prism software (version 9.3.0; GraphPad Software, Inc) was used for analyses and visualization. This activity was reviewed by CDC and conducted consistent with applicable federal law and CDC policy.§§§

During March 2020–August 2021, a total of 5,918,199 patients in PCORnet health care systems were tested¶¶¶ for SARS-CoV-2, and 805,276 (13.6%) test results were positive (Table 1), representing approximately 3.0% of all positive results reported to CDC (Supplementary Table, https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/113252). These patients are similar demographically to those included in CDC case data by age, sex, race, and ethnicity. Geographically, patients in the Census Pacific division are underrepresented whereas those in the Mountain division are overrepresented. Among patients with a positive test result, 2.9% were Asian, 15.7% Black, 61.2% White, and 10.9% Other race; 18.6% were Hispanic and 71.7% were non-Hispanic ethnicity (Table 1). Compared with all persons with a positive SARS-CoV-2 test result, a higher proportion of patients with high-risk comorbidities**** were treated with mAb. Critical care†††† was required by 3.4% of all persons with positive test results compared with 1.8% of those treated with mAb.

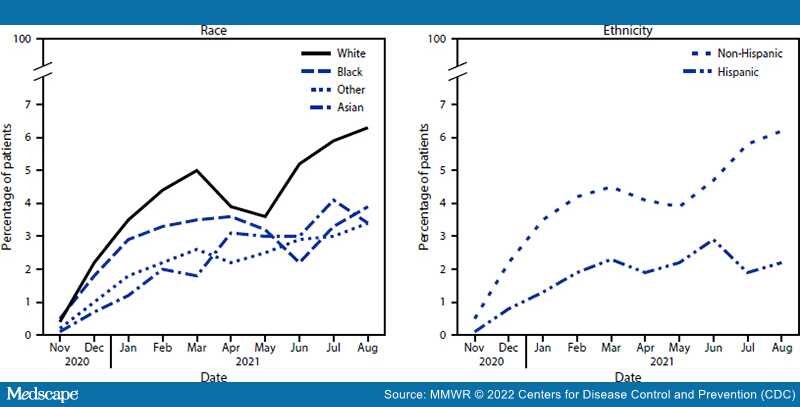

Mean monthly mAb use among all patients with positive SARS-CoV-2 test results who were White, Black, Asian, or Other race was 4.0%, 2.8%, 2.2%, and 2.2%, respectively; among patients of Hispanic or non-Hispanic ethnicity, mAb use was 1.8% and 4.0%, respectively. Patients who were Black, Asian, or Other race received mAb 22.4%, 48.3%, and 46.5%, respectively, less often than did White patients (Table 2); systematic temporal differences in mAb receipt were observed by race (all pw<0.01) (Figure). SARS-CoV-2 positive patients of Hispanic ethnicity received mAb 57.7% less often (pt<0.001) than did non-Hispanic patients; systematic temporal differences in mAb receipt were observed by ethnicity (pw = 0.002).

Figure.

Monthly* percentage of COVID-19 patients (n = 805,276) receiving monoclonal antibody treatment,† by race§ and ethnicity¶ — 41 health care systems in the National Patient-Centered Clinical Research Network — United States, November 2020–August 2021

*Systematic temporal differences in medication receipt by race and ethnicity were assessed by pairwise Wilcoxon signed rank test.

†mAbs require administration by intravenous infusion or subcutaneous injection.

§White race is the referent group; p-values for Black, Asian, and Other races are 0.004, 0.002, and 0.002, respectively.

¶Non-Hispanic ethnicity is the referent group; p = 0.002 for Hispanic ethnicity.

Mean monthly dexamethasone use among inpatients who were White, Black, Asian, or Other race was 35.8%, 33.8%, 31.4%, and 34.2%, respectively; among patients of Hispanic or non-Hispanic ethnicity, dexamethasone use was 32.5% and 35.4%, respectively. Relative disparities in dexamethasone receipt by race were not statistically significant (Table 2); however, small but systematic temporal differences in dexamethasone receipt were observed among White inpatients and Black, and Asian inpatients (both pw<0.05) (Supplementary Figure, https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/113252). Hispanic inpatients were treated with dexamethasone 6.2% less often than were non-Hispanic inpatients and systematic temporal treatment differences were also observed (pw = 0.005).

Mean monthly remdesivir use among inpatients who were White, Black, Asian, or Other race was 29.0%, 31.2%, 26.2%, and 30.6%, respectively; among patients of Hispanic or non-Hispanic ethnicity, remdesivir use was 30.4% and 29.3%, respectively. Black inpatients received remdesivir 9.3% more often (pt = 0.03) than did White inpatients; systematic temporal differences were also observed (pw = 0.03). Asian, Other race, and Hispanic inpatients did not experience significant relative disparities or systematic temporal differences in remdesivir treatment compared with White and non-Hispanic inpatients.

Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2022;71(3):96-102. © 2022 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)