This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Matthew F. Watto, MD: I'm Dr. Matthew Watto here with my very good friend, Dr Paul Nelson Williams. We are going to be talking about celiac disease, based on our recent podcast episode with Dr Amy Oxentenko. This was a really fantastic podcast. Where should we start?

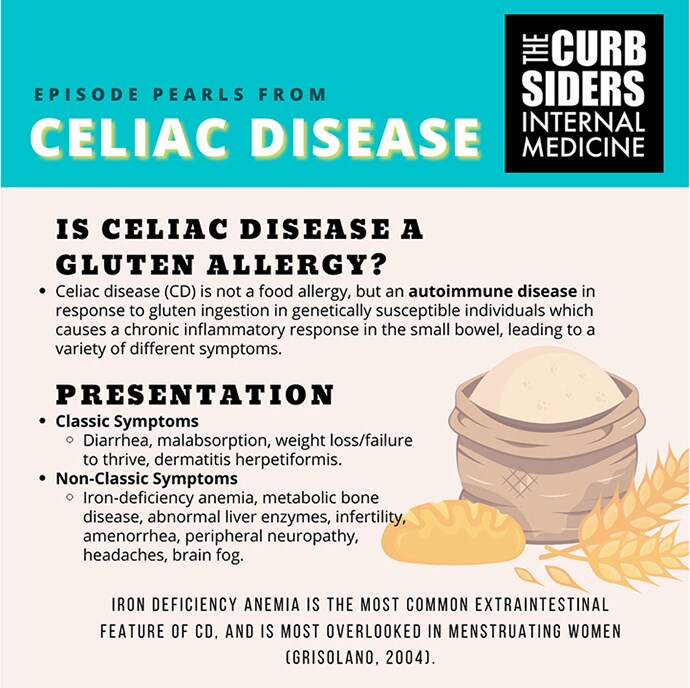

Paul N. Williams, MD: The beginning. I don't think I realized how prevalent celiac disease is; 1% of the US population has the diagnosis. So we need to have a relatively low threshold of suspicion.

The classic presentation is a young woman in her 20s or 30s with diarrhea, weight loss, and perhaps some symptoms of malabsorption. But it's worth noting that 15% of patients present with constipation rather than diarrhea. Patients can be obese or even much older; 20% are age 60 or above at the time of diagnosis, which I found to be a stunning number.

Figure 1.

So instead of a classic picture, be mindful of and look out for other clues, such as iron deficiency anemia. We spent a lot of time talking about that as well. One point that Dr Oxentenko made that I thought was fascinating was that we often miss celiac disease in young menstruating women because we attribute their iron deficiency anemia to their menses, and we don't do any kind of further workup or even take a good GI history. As a result, these patients are probably underdiagnosed. I found all that stuff really helpful. We should start just by thinking of celiac disease more frequently, particularly when there is evidence of micronutrient deficiency or malabsorption.

Watto: Other clinical pictures include low bone density and elevated liver enzymes that don't make sense. Celiac disease is common and the symptoms aren't always classic.

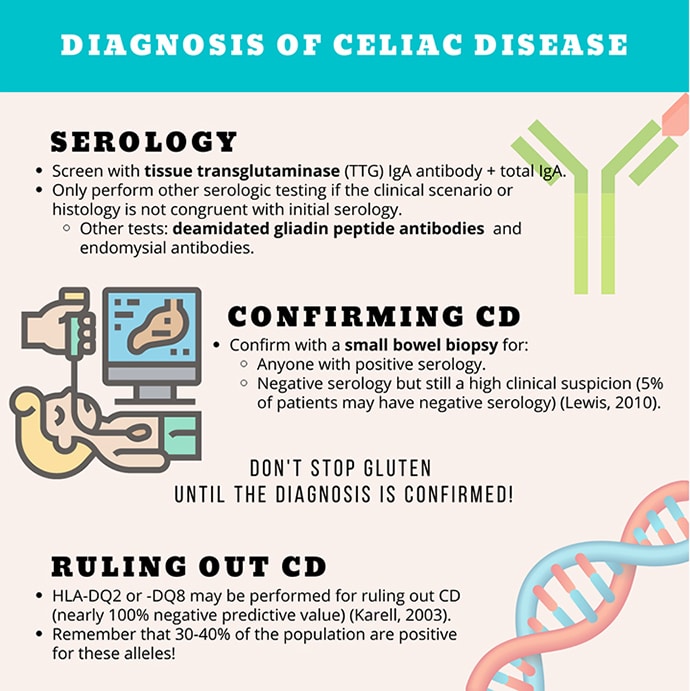

What do we do if we think a patient might have celiac disease? The workhorse test is the tissue trans-glutathione (tTG). You should check a total IgA level also because a certain percentage of the population is IgA-deficient. If they are IgA-deficient, then you might get a false-negative tTG IgA level. In those cases, you would have to go to one of the second-line tests for celiac disease, such as deamidated gliadin peptide antibodies or endomysial antibodies.

Figure 2.

For me, Paul, one of the biggest take-home points was that most patients are going to need a biopsy to confirm the diagnosis. I thought it was simpler — you make the diagnosis and then you go from there. But it turns out there is more to it.

Williams: Another point worth mentioning is that the biopsy is supposed to happen while the patient is still consuming gluten. A common mistake is making a presumptive diagnosis based on serology and telling the patient to cut gluten from their diet to see how they do. But that lowers the diagnostic yield of the biopsy significantly.

Watto: I've definitely seen that in the semi-recent past. We made the diagnosis and the patient was gluten-free at the time of biopsy, so the gut was partially healed already. That's good for the patient, but you don't want to question the diagnosis.

Dr Oxentenko told us that guidelines say patients should follow a gluten-containing diet for at least 2 weeks before a biopsy, but she recommends 8 weeks to avoid any diagnostic uncertainty. It doesn't have to be a ton of gluten — they don't have to eat a loaf of bread a day. A slice of bread is probably enough gluten for a positive biopsy.

If the patient is already on a gluten-free diet and they don't want to come off it because they feel well, you can do genetic testing, which tests for two different mutations. Both have high negative predictive value, so it's helpful in ruling out celiac disease. However, about 30% of the population has those mutations without having celiac disease.

Williams: The genetic stuff is fascinating. One thing I've missed, and I look forward to correcting, is that it's recommended to screen family members for celiac disease as well. That can be done with serologic screening. You don't necessarily have to do the fancy-pants genetic testing.

Watto: Basically they have to tell their parents or their kids to get tested for celiac disease as well.

Let's talk about after the diagnosis. Our patient had really high titers and a positive biopsy. What else do we need to do? What follow-up is needed?

Figure 3.

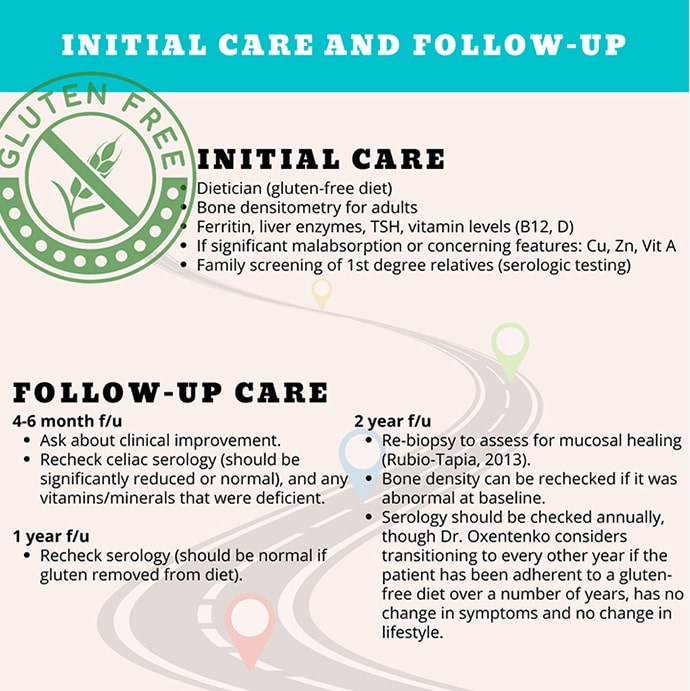

Williams: Some of this will already have been done during the workup for iron deficiency anemia or other symptoms. Vitamins B12 and D, ferritin, and liver function tests are kind of requisite if you haven't done them already.

But the most important thing is referring the patient to a dietician who is comfortable with the gluten-free diet. That is probably the biggest favor you can do your patient, to get them to see the dietitian and talk through how to eat in a way that will help minimize their disease. If the patient isn't already on a gluten-free diet, you can follow the serologies to see how the patient is doing after eliminating gluten.

Watto: You can repeat the serologies at least once a year. She also re-biopsies people, usually about 2 years after being on a gluten-free diet. Patients might continue to have positive titers or a positive biopsy if they aren't adhering to the gluten-free diet or they are inadvertently ingesting gluten in their diet. You can help mitigate that is by having them meet with a dietitian familiar with the gluten-free diet.

Williams: There were some counseling points in this episode that I'm going to start mentioning to patients. One was about restaurant menus. Someone did a study of gluten-free items on restaurant menus to see whether they were truly gluten free, and it turns out they aren't. Patients need to let restaurant staff know that this isn't just gluten intolerance — that they have celiac disease and can't eat gluten at all.

Watto: This episode was packed full of pearls. We'll go too long if we try to recap all of them here, so people can definitely head to our website to check out Celiac Disease With Dr Amy Oxentenko.

Follow Medscape on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube

Credits

Image 1: The Curbsiders

Image 2: The Curbsiders

Image 3: The Curbsiders

© 2022 WebMD, LLC

Cite this: How to Not Miss Celiac Disease - Medscape - Feb 15, 2022.

Comments