In September 2020, I wrote about the risk to rural communities of being overrun with COVID from prisons. That was prompted by the 2020 plans to use West Virginia prisons FCI Gilmer and FCI Hazelton as quarantine sites for the entire Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) system. In addition, prisoners from the overcrowded DC jails would also be sent to these two facilities before being sent yet again to another one after 14 days of quarantine. Part of the concerns were that the BOP's screening was security theater — a worthless temperature check and questions, but no COVID testing. Gilmer had an outbreak affecting at least 83 prisoners and additional staff after receiving 124 inmates. After that, pressure by Governor Jim Justice and Senator Joe Manchin thankfully brought this plan to a halt.

At the time, I was part of a local NIMBY movement not wanting the COVID prisoners in Hazelton, which is near my community. Immigrant detention centers, prisons, and meatpacking plants are often placed in rural communities, where there is less chance of protest and more chance that the locals can be seduced by the promise of jobs.

Being rural and economically depressed, western Maryland and nearby West Virginia made the ideal dumping ground for several federal and state prisons.

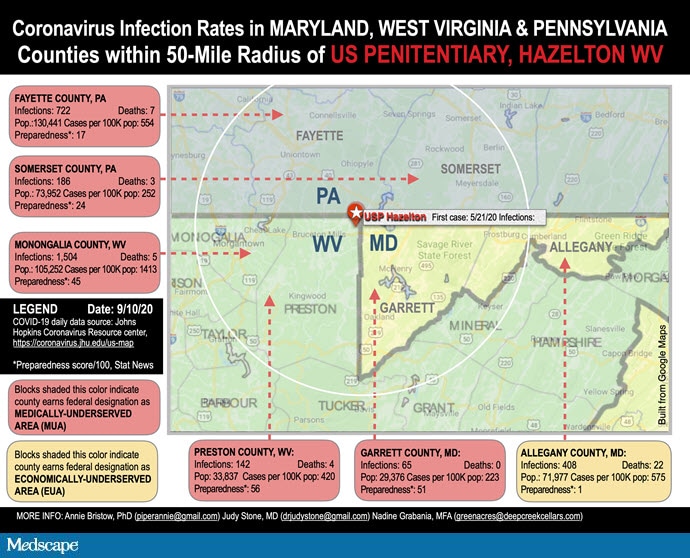

But our concern was also grounded in data that was compiled by members of our local Women's Action Coalition.

Many of the country's largest outbreaks had occurred in prisons or jails. This should be no surprise. Inmates are crowded together in poorly ventilated cells. They were given flimsy, almost gauze-like single-ply masks. When vaccinations became available, prisoners were often a low priority.

Prison guards across the country have also been more reluctant than many others to receive the COVID vaccine, although they were prioritized to be vaccinated. I have not received response to my inquiry about that to prison staff. As of April, "the median vaccination rate — i.e. the percentage of staff who had at least one COVID-19 vaccine dose — was only 48%." Yet this was still far higher than the rate among the prisoners.

In our county, only 48% are fully vaccinated compared with 70% for Maryland. Allegany and Garrett counties have pretty consistently had the lowest vaccine rates and the highest test positivity, currently. We are a relatively poor and elderly area, with a "preparedness score" of only 3 out of a possible 100. In comparison, Baltimore County had a score of 34 (low) and Carroll was the highest in Maryland, at 86.

As I noted in my Forbes article last year, "About a quarter of the 800 prison staff live in Allegany county. If they become ill and spread the virus in the community, it will hit hard—we have 23% living in poverty in Cumberland (compared to 9% statewide), 17% older than 65, 8.6% of those younger than 65 have a disability, and a per capita income of $22,268. Nearby Preston County, WV, Garrett County, MD and Fayette County, PA, where other prison employees live, fare somewhat better on those measures, except for a similarly elderly population."

The risk of acquiring COVID is sixfold higher in prison than in communities. The unfairness of it really hit me when I saw the recent headline that a 68-year-old prisoner at Hazelton, aka "Mount Misery" FCI, had died of COVID. At the time, West Virginia's WBOY News notes, the medical isolation rate at the FCI was > 7% or more, the facility vaccination rate was 50% or less, and the rate of COVID transmission in the surrounding community was 100 or more per 100,000 people — a "Level 3" for COVID, or high risk.

While there were supply shortages early in the pandemic, there is no reason now that prisoners should not be cared for by fully vaccinated and masked staff and with provided better masks and ventilation. Imprisonment shouldn't be a death sentence.

Follow Medscape on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube

She survived 25 years in solo practice in rural Cumberland, Maryland, and now works part-time. She especially loves writing about ethical issues and advocating for social justice. Follow her at drjudystone.com or on Twitter @drjudystone.

Credits:

Image 1: Annie Bristow, PhD; Judy Stone, MD; Nadine Grabania, MFA

© 2022 WebMD, LLC

Any views expressed above are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the views of WebMD or Medscape.

Cite this: Judy Stone. Some Prisoners Face Risk for COVID From the Community - Medscape - Jan 13, 2022.

Comments