Mechelle and Tim Giles started their 35th wedding anniversary celebration in a hospital room. It was especially poignant. Mechelle was hours away from discharge after becoming the first woman to receive an Aeson totally implantable artificial heart.

Tim and Mechelle Giles

Her 10-year journey to this milestone began at a health fair in Adair County, Kentucky, with a surprising diagnosis of diabetes. After a losing battle with fluid buildup and progressive weakness, punctuated by a pacemaker implant and blood clots, she was eventually transferred to University of Louisville Health's Jewish Hospital in Louisville, Kentucky.

Mechelle Giles with one of her surgeons, Mark Slaughter, MD

Many serious conversations followed with her husband, and her cardiothoracic surgeons Mark Slaughter, MD, and Siddharth Pahwa, MD. "They said the LVAD was no longer an option," her husband Tim said, referring to a left ventricular assist device.

"They said there is only one other thing we can do, and that's the mechanical heart. I took his word for it and here I am. I trust him," said Mechelle, referring to Slaughter.

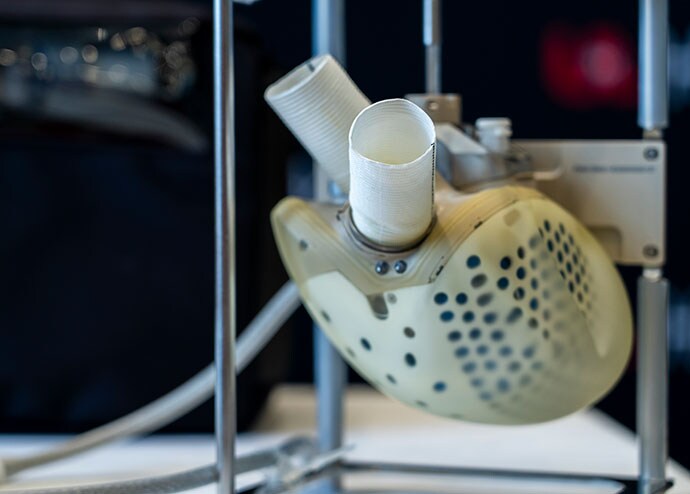

The Aeson artificial heart by Carmat

In a Zoom interview with media, Mechelle sat next to her husband. "I feel great," she said, her smile waning when the device alarmed in the background.