A new type of neuroscience-informed, magnetic brain stimulation has resulted in remission of treatment-resistant depression in almost 80% of patients enrolled in a randomized sham-controlled trial in findings that support earlier results of an open-label trial.

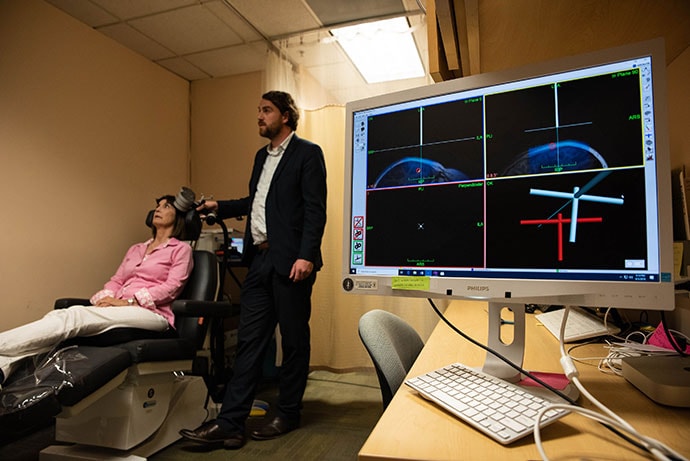

Dr Nolan Williams demonstrates Stanford neuromodulation therapy on study participant Deirdre Lehman.

"It works well, it works quickly and it's noninvasive. It could be a game changer," study investigator Nolan Williams, MD, an assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford University in California, said in a news release.

"This is really the first time that functional neuroimaging has been utilized as a part of a treatment in psychiatry in a prospective way. This is a rapid-acting neuromodulation treatment for depression and there really isn't one of those yet clinically approved," Williams told Medscape Medical News.

The study was published online October 29 in the American Journal of Psychiatry.

5 Days of Treatment, 4 Years Depression-Free

Stanford neuromodulation therapy (SNT) — which was previously known as Stanford accelerated intelligent neuromodulation therapy (SAINT) — is a high-dose, resting-state, functional connectivity magnetic resonance imaging–guided intermittent theta-burst stimulation (iTBS) protocol.

SNT advances repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration by targeting the magnetic pulses according to each patient's neurocircuitry and providing a greater number of pulses at a faster pace.

The SNT protocol involves 5 consecutive days with a total of 10 iTBS sessions per day at 1800 pulses per session, with 50-minute intervals between sessions. TMS requires 6 weeks of once-daily sessions and has been only modestly effective in inducing remission, the authors note.

The current trial enrolled adults with long-standing treatment-resistant depression currently experiencing moderate to severe depressive episodes, with random assignment to receive active or sham SNT.

The trial was halted early after a planned interim analysis demonstrated a large effect size of active compared with sham SNT (Cohen d > 0.8).

The mean percentage reduction from baseline in Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) score at 4 weeks (primary outcome) was 52.5% in the active SNT group compared with 11.1% in the sham SNT group.

Overall, across the 4-week follow-up, 12 of 14 patients (85.7%) in the active SNT group met the criterion for response (a reduction ≥ 50% in MADRS score), and 11 (78.6%) met the remission criterion (MADRS score ≤ 10) in at least one of the five post-treatment assessments.

In the sham SNT group, four of 15 patients (26.7%) responded and two (13.3%) remitted at some point during the 4-week follow-up.

"We saw very robust effects in the active group and we didn't see any placebo effect at all in the sham group," said Williams.

"There is certainly a subgroup of patients that may need repeated treatments, but our first subject in this trial, I think he's still well at 4 years with just a week of treatment," Williams said.

In line with the earlier open-label study, SNT was well-tolerated and no serious adverse events occurred during the trial. The side effect profile was similar to rTMS, with a greater incidence of headache in the active SNT group.

"The short treatment course and the high antidepressant efficacy of SNT present an opportunity to treat patients in emergency or inpatient settings where rapid-acting treatments are needed," the authors write.

"The large effect size of SNT may be due to several factors. The SNT protocol was designed from neuroscience-informed stimulation parameters and was selected to optimally modulate the targeted neural circuitry," they add.

They caution that the sample size was small and the SNT protocol has only been tested at Stanford in a highly educated sample.

Huge Potential, Needs Replication

Reached for comment, Timothy Sullivan, MD, chair of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, Staten Island University Hospital, New York City, noted that the field of neuromodulation is developing very quickly.

"Transcranial magnetic stimulation has been around for a number of years, but the results have always been kind of unimpressive," he told Medscape Medical News.

The Stanford approach is "very interesting and it follows on a lot of research that's been done using functional MRI in people with depression to identify specific neural circuitry that are functioning abnormally," Sullivan added.

"So, in that regard, it's conceptually interesting and exciting that they were able to see significant improvement in a relatively short period of time. If the 80% rate were to be borne out, eventually, that's getting pretty close to the response rate for a ECT [electroconvulsive therapy], and obviously with much less risk, much less morbidity," Sullivan said.

He cautioned that the results need to be replicated at other centers and with larger numbers of patients. "Certainly if we can come close to replicating this level of response, it'll be a dramatic innovation," Sullivan said.

The research was funded by a Brain and Behavior Research Foundation Young Investigator Award, Charles R. Schwab, the David and Amanda Chao Fund II, the Amy Roth PhD Fund, the Neuromodulation Research Fund, the Lehman Family, the Still Charitable Trust, the Marshall and Dee Ann Payne Fund, and the Gordie Brookstone Fund. Williams is a named inventor on Stanford-owned intellectual property relating to accelerated TMS pulse pattern sequences and neuroimaging-based TMS targeting; has served on scientific advisory boards for Otsuka, NeuraWell, Nooma, and Halo Neuroscience; and has equity/stock options in Magnus Medical, NeuraWell, and Nooma. Sullivan has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Am J Psychiatry. Published online October 29, 2021. Abstract

For more Medscape Psychiatry news, join us on Twitter and Facebook.

- 1

Credits:

Lead Image: Steve Fisch

Image1: Steve Fisch

Medscape Medical News © 2021

Cite this: Megan Brooks. Novel Brain Stimulation a Game Changer for Severe Depression? - Medscape - Oct 29, 2021.