On the 21st hour of our return journey from Israel to our hometown of Glasgow, Kentucky, we boarded a plane at JFK. Only one person in business class. Good. Ten in Comfort Plus and eight people behind us in the main cabin. We could practice social distancing. From my window seat, I began to consider all the risks we had encountered as an unusually quiet New York City morning unfolded below us. The United States was a very different place from the one we left only 2 weeks earlier.

The flight from Tel Aviv to JFK was crowded. As the plane’s nose went up, my eyes became heavy and I started to drift. Then I heard it: a cough in the row ahead.

Maybe a cold or the good old-fashioned flu, I hoped. But it became incessant. I shot a look at my husband, Tony, who rolled his eyes. Once the seat belt sign went off, I unbuckled to take a surreptitious look at the passenger guilty of the cough. She was a frail, elderly lady hunkered down in her seat, eyes closed, barely able to maintain an upright position. Her face mask was damp, wilted, and limp-fitting around her nose and mouth.

“Her cough is pretty wet,” I whispered to Tony when I returned. “The COVID-19 cough is dry, so I’m guessing bacterial pneumonia or, worse, cancer. She’s pretty sick.“ He seemed marginally reassured, but we agreed it was one more reason to self-quarantine once we were back home. My parents are 89 and 88, both with advanced lung disease. My best friend is in a wheelchair because of multiple sclerosis, and my niece has cystic fibrosis.

Another potential exposure occurred when the passport control officer at JFK sent us to the high-risk traveler area for a temperature check and to complete a questionnaire. At that time, social distancing was not yet the rule—I was seated 6 inches from the next high-risk traveler.

Once we landed in Nashville, our luggage was traversing the carousel alone, a first. We rode an empty airport shuttle to the parking spot. We confessed to the driver that we’d just come from Israel and told him we were high-risk travelers. He was unflustered. We felt well, and we’d been careful to sanitize our hands and wipe down every inch of anything we’d touched on the planes.

This Could Be Bad

By January, I had suspected that this novel coronavirus could be something, but I’d thought our trip might be far enough ahead of the spread that we could make it. Despite having travel insurance, “fear of travel” was not deemed a reasonable cause for cancellation. The day after our arrival in Israel, we spent a fabulous afternoon at the edge of the Dead Sea. Tony donned his swim trunks and floated on top of the water for 30 minutes, laughing and deadpanning for the camera. All seemed well. The next day, Jericho and Bethlehem were closed to tourists after a traveler tested positive.

As I was the only physician in a group of 49 travelers, the tour guide summoned me to the front of the bus. “The group ahead of us is stuck in Bethlehem in lockdown at the Angel Hotel. They can’t move for 14 days. Do you think we should offer everyone an opportunity to make arrangements to go home now?” Instead, we opted to pass along information about social distancing, hand sanitization, and concerning symptoms. The guide handed me the microphone, and I belted out a brief synopsis of the medical situation as I understood it.

There were a few questions. One of the group had asthma and was concerned that others might think he had the virus. I gave him decongestants and antihistamines and told him to check his temperature. Our trip continued. We toured the Qumran Caves, the site of the Dead Sea Scrolls discovery. We took in the breathtaking views from Masada. We learned about the ancient Jewish stronghold and the tragic stories of suicide, and we saw glimpses of ancestral traditions and even descended into a mikvah, a ceremonial cleansing bath.

Then, I saw one of our party run over to another tour group to start a cheery conversation. My heart sank when I saw one of them was coughing. I gently reminded everyone NOT to engage anyone beyond a distant courtesy. Between tour sites, I read the live Twitter feed coming out of Italy. There was an urgent plea for help for a fellow physician who was crashing. I took a screenshot of all the suggestions coming in from those on the front lines.

When the Muslim call to prayer awoke us in Jerusalem at 4 am (again), I switched on the news to more calls for travel bans. Crowds dwindled in the usually packed Jerusalem markets. Some streets were completely empty. A growing anxiety to be back home crept into periods of meditation and prayer. Texts and private messenger communications from family beseeched us to come home.

But by that time, it was too late. Our calls to our airline were met with -6-hour waits, to no avail. On March 15, the 12-day tour, which had taken 5 years to plan and finalize, was over. Most of our group left immediately. We had 1 more day. Despite the pouring rain, and after checking that there were no reports of COVID-positive patients in Jerusalem, we walked from our hotel door to Absalom’s tomb, the house of Caiaphas, where Peter denied Christ. The Kidron Valley and its surrounding sites, normally packed with buses, was now empty except for three other tourists we saw in the distance. We were relieved when they abruptly took a different path. They were probably avoiding us, and who could blame them?

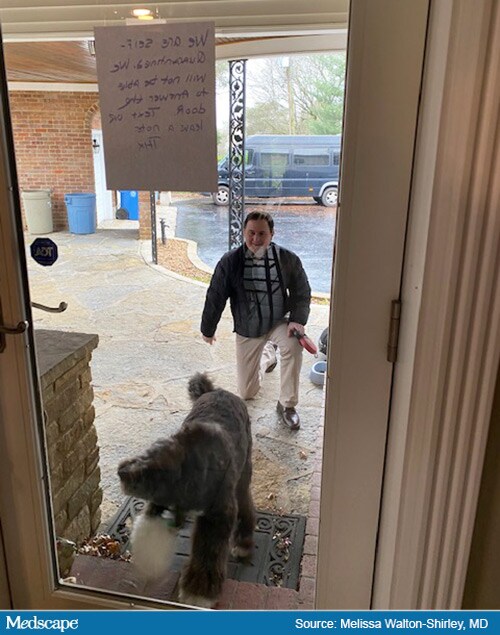

Once home, we posted self-quarantine signs on all the doors. My brother dropped off perishables, and our neighbor brought our dog home from the day care. We spoke to him through the glass. I canceled my locums work in Montana.

We have now completed our self-quarantine and feel well.

With the benefit of hindsight, I now question our decision to travel. While we had discussed how this novel coronavirus may unfold on a global scale and the anticipated trajectory of spread, I had thought we could make it in and out in time. It was likely an unnecessary gamble. Like everyone else, we were caught wondering if we were being melodramatic about the worry.

We are grateful that we are still seemingly healthy, but there are worries everywhere about inadequate testing and the lack of protective equipment for medical workers. Like most everyone, I obsessively monitor Twitter, Facebook, and multiple news outlets for updates. I post information and warnings about the severity of this outbreak to my Facebook friends, who are hungry for medical information and advice. Like so many, I’m just trying to do my part from my little spot in the world.

I am still scheduled to work in Montana in mid-May. A lot could happen between now and then. I have no way of knowing if I’ll make it there, or if I’ll be welcome. I see this pandemic unfolding over months, not weeks. As for the future, it abounds with uncertainty.

Melissa Walton-Shirley, MD, is a native Kentuckian who retired from full-time invasive cardiology. She enjoys locums work in Montana and is a champion of physician rights and patient safety. In addition to opinion writing, she enjoys spending time with her husband, daughters, and parents and sidelines as a backing vocalist for local rock bands.

Follow Melissa Walton, Shirley on Twitter

Follow theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology on Twitter

© 2020 WebMD, LLC

Any views expressed above are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the views of WebMD or Medscape.

Cite this: Melissa Walton-Shirley. Traveling in the Shadow of a Pandemic - Medscape - Apr 06, 2020.

Comments