Editor's note: Find the latest COVID-19 news and guidance in Medscape's Coronavirus Resource Center.

When the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) struck in 2003 - 2004, approximately 20% of infections overall occurred in frontline healthcare workers. In Greater Toronto, the North American epicenter of the outbreak, that number more than doubled, to 43%, and two nurses and a physician died.

That represented a double blow: for the infected professionals themselves and for the patients whose care suffered while the essential services of the recovering professionals were rationed. And now, the memory of those statistics hangs like a specter over medical staff battling SARS's new sister virus, SARS-CoV-2, the contagion that causes COVID-19.

"We can't stop COVID-19 without protecting our health workers," Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, director-general of the World health Organization, said at a recent media briefing.

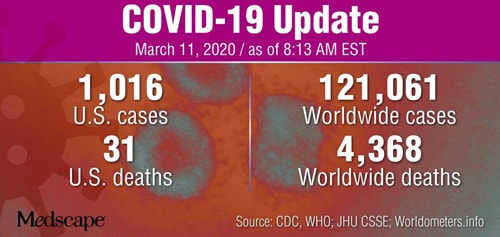

But with the United States bracing for exponential increases in confirmed cases — as of March 11 they totaled at least 1016 across 38 jurisdictions with 31 deaths — and moving from containment to mitigation, healthcare workers doubt enough is being done to protect them and ensure continuity of patient care in already stressed medical centers.

For one thing, as the outbreak disrupts global supply chains, some US facilities are reporting shortages of personal protective equipment (PPE) such as masks, goggles, respirator helmets, gloves, and gowns, according to a report in The Seattle Times. Employees are being asked to ration stock.

"Time to Step Up"

Doubts about adequate safety measures are top of mind among registered nurses in New York state, where poor access to PPE, scant training in equipment use and protocols, and improper assessment and triage of patients are being reported by the nurses association.

In a recent nationwide survey of 6500 members by the union National Nurses United (NNU), only 30% of respondents said their employers had sufficient PPE in stock to safeguard staff against a sudden COVID-19 spike. Just 44% said employers had trained them in recognizing and responding to suspected cases.

"Nurses are confident we can care for COVID-19 patients, and even help stop the spread of this virus, if we are given the protections and resources we need to do our jobs," said Bonnie Castillo, RN, executive director of the NNU and the California Nurses Association at a March 5 press conference. "This is not the time to relax our approach or weaken existing state or federal regulations. This is the time to step up all of our efforts."

Sensing a vacuum at the top, the union has petitioned the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), calling for sweeping safeguards, including employer education for healthcare workers and maximum protections such as negative pressure rooms and adequate gear.

"Employers shall plan for surges of patients with possible or confirmed COVID-19, including plans to isolate, cohort, and to provide safe staffing," an NNU statement said, recommending that exposed healthcare workers should be given a minimum 14-day precautionary leave with full pay and benefits.

The NNU also cited the troubling case of one symptomatic Northern California Kaiser Permanente nurse who complained of being initially refused testing by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on the grounds that she had not been wearing the "recommended" PPE when exposed to an infected patient (which she disputed), and later because she did not have the proper "identifier number."

In hard-hit Washington State, medical and nursing associations released a joint statement stressing gaps in effective protections and communication protocols.

Sally Watkins, PhD, RN, executive director of the state's nurses' association, told Medscape Medical News that the concerns of frontline caregivers need prompt attention. "We continue to hear from members who say they are not getting the protective equipment and timely information they need."

"Conflicting Guidance"

While the situation is in rapid flux, Watkins conceded, "Nurses are confused. Not only do hospitals continue to play catch-up on protocols for handling suspected and confirmed COVID-19 cases, but nurses are also hearing conflicting guidance on issues such as the necessary PPE to do their jobs safely."

For example, she said, while N95 respirators are considered the best protection for procedures involving aerosolization, "many infectious disease experts are now reporting that due to the droplet transmission of COVID-19, surgical masks may be used. We need to ensure adequate supplies of all necessary PPE are available including N95 respirators for aerosolized procedures."

And as more symptomatic workers are sent home to wait out a quarantine, the ranks of staff are thinning. The city of Kirkland, in Washington, home to the epidemic's ground zero at the Life Care Center nursing facility already linked to at least 19 deaths, announced that a federal strike team of traveling medical personnel was being flown in as backfill to assist beleaguered staff.

At least 70 symptomatic workers at the facility have been asked to stay home. Similarly, the University of California Davis Medical Center sent home 36 registered nurses and 88 other healthcare workers last month, according to NNU, after the admission of a single coronavirus patient. Dozens of hospital workers were told to go home at Kaiser Permanente's Westside Medical Center in Hillsboro, Oregon.

In the face of the country's struggling testing program, one proactive move in Washington state is worth noting: Seattle's University of Washington Medical Center has established a drive-through test clinic that prioritizes symptomatic healthcare workers, swabbing their nostrils through rolled-down windows in its parking garage. According to National Public Radio, those testing negative go back to work as quickly as possible, while positives are quarantined at home.

In the east, the New York State Nurses Association is also urging the federal and state governments to take immediate action to protect healthcare workers.

Currently, OSHA has no infectious diseases standards in place to protect these employees from COVID-19. In addition, the state health department has yet to issue mandatory orders and protocols to protect healthcare workers and patients alike.

Strict controls, however, do protect frontline staff and patients, as a recent study from 43 public hospitals in Hong Kong suggests, as reported by Medscape Medical News. Stringently enforced measures, including the general distribution of masks, resulted in no infections by medical workers and no hospital-acquired cases overall in the first 6 weeks of the outbreak in mainland China.

A similar aggressive containment strategy by Singapore, another city state, is considered by some a model for response, according to a recent report by the New York Times.

In Singapore General Hospital's radiology department, COVID-19 response has been shaped by the SARS experience almost 2 decades past, research in the American Journal of Roentgenology shows.

At that time, protocol changes included segregation of workflows for inpatients, outpatients, and febrile vs nonfebrile cases. Greatly enhanced infection prevention and control measures were the norm, with all staff knowing their N95 mask type and becoming proficient in the use of PPE, hand sanitizers, and disinfectant wipes.

"To this day, radiology SARS veterans will disinfect their workstations before starting work, much to the amusement of their younger colleagues," Lionel Tim-Ee Cheng, MBBS, a radiologist at Singapore General Hospital, wrote in the journal.

Training and Cooperation

Thinking back to the H1N1 outbreak of 2009, Thomas M. File, MD, chief of the Infectious Disease Service at Summa Health System in Akron, Ohio, said that the key is to reeducate and retrain all healthcare workers, no matter what their function in care, according to the demands of each new infectious crisis.

"There are protocols for control in place, but staff have to be trained in the protocols that apply to the specific standards for each type of outbreak," he told Medscape Medical News.

As for the reported shortages of protective gear, these need to be addressed at the federal level. "I hope the appropriations bill signed last week by the president will provide some accommodation for manufacturing protective equipment," said File, who is also a spokesperson for the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

The $8.36 billion bill included $3.1 billion to the Office of the Secretary of Health and Human Services, with $100 million going to community health centers, and these funds may facilitate the purchase of additional supplies.

According to Aaron E. Glatt, MD, an infectious disease specialist at Mount Sinai South Nassau in Oceanside, New York, US hospitals' existing infection control guidelines are capable of achieving low staff transmission rates similar to those seen in Hong Kong — if they are followed to the letter. But if these protocols involve adequate supplies of protective gear, that could be a challenge for the near future.

After the 375 cases of SARS in Toronto, a specially commissioned Ontario SARS report released in 2007 concluded that the healthcare system was inadequately prepared for the crisis and especially lacked the ability to protect frontline medical staff. As the report presenters wryly noted, hospitals are just as dangerous workplaces as mines and factories but have fewer measures to protect staff.

Vicki McKenna, RN, who worked in the trenches during the SARS outbreak in Toronto, is still haunted by the high infection rate and three deaths in healthcare staff. Now president of the Ontario Nurses Association, she says lessons were learned but perhaps not implemented.

"We came to understand as nurses that in the absence of scientific certainty, you must err on the side of caution," she told Medscape Medical News. "But there were attempts at many levels to minimize the problem and not to listen to the concerns of frontline workers."

A familiar refrain to today's circumstances? "Nurses need to speak up and be heard," McKenna said.

Ultimately, what is needed is cooperation. "Everyone is working jointly — and very hard — to ensure that the COVID-19 outbreak is being responded to in the best and most rapid way possible," Watkins said. "This is an extraordinary public health emergency and calls for our community to work together."

For more news, follow Medscape on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube.

Medscape Medical News © 2020

Cite this: COVID-19: Who's Protecting the Protectors? - Medscape - Mar 11, 2020.

Comments