At a session on "Emergency care in response to terrorist attacks" at the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Congress, I was expecting to learn about the cardiologist's role. I imagined us perhaps manning echo stations or attending to those with stress-induced cardiac instability. Instead I learned that we all need to brush up on our first-responder emergency medicine skills.

I first noted a change in Paris in 2015, when my daughter and I visited. It was not the same city of a few years prior. AKA-laden troops awaited visitors to the Louvre and Notre Dame.

And just 6 weeks later, suicide bombers and snipers killed 130 innocents at multiple venues across the city, including a soccer stadium, a concert hall, and numerous cafes and restaurants.

Lessons From Nice and Paris Attacks

It is unfortunate that the session's presenters, Pierre Carli, head of the emergency medical service SAMU in Paris, and Jacques Levraut, a professor of emergency medicine from the Pasteur Hospital in Nice, became experts by having directly dealt with such attacks in their respective cities.[1]

Carli, described an encounter with a cardiologist who became an accidental first responder because his office overlooked the site of one of the attacks. "It was the first time in my life that a cardiologist asked me for orders"," he said, emphasizing the need for physicians to be prepared to work outside of their specialty, in the face of increased terrorist attacks the world over.

He pointed out that flexibility is paramount for successfully treating as many victims as possible on the scene. In their response plan, the area of danger is designated the red zone, where the doctor is not allowed to enter and the victim must be extracted for care.

"On November 13th we thought we were ready…but it was impossible to see what were the green zones and what were the red zones. There were active shooters on the run", he recalled.

On that day the Bataclan Theater held 1400 public hostages and the shooting occurred over 3 hours. "There was shooting from the stage as well," he said, making victim extraction dangerous, prolonged, and difficult.

He emphasized quick prehospital damage control, pointing out the effectiveness of tourniquets for hemostasis and the need for rapid triage. After one attack, triage occurred in under 46 seconds per victim. With trauma victims, if cardiopulmonary resuscitation is already in progress at the scene, clinicians must go on to help those who are viable. It struck me that this is in complete distinction to the 20-minute codes cardiologists run for a primary ventricular fibrillation arrest.

Only after others have been assisted should one focus on those with a smaller chance of survival.

Practice Drills

Based on lessons learned from prior attacks in London and Madrid, they had practiced drills. But the problem is that although "you know when the attack is beginning, you don't know when it will end," cautioned Carli.

French medical, police, and military personnel have ramped up their training. They hold "mega drills" that can involve as many as 2000 participants. They also use toy models, including a Playmobil set to map out on a smaller, more manageable scale and routes of both rescue and escape.

The presenters believe that medical students should be taught how to respond to a mass attack, such as the 4-day training course attended by all fifth-year medical students at Paris Descartes University.

Carli's focus then shifted to the future. He projected that the next wave of attacks may be different from what we have seen in the past. For instance, an ambulance could be hijacked in order to target a healthcare facility. "Providers must maintain the quality of care despite on-going aggression. This has been the case in the US where there has been a vast experience with mass shootings," he said.

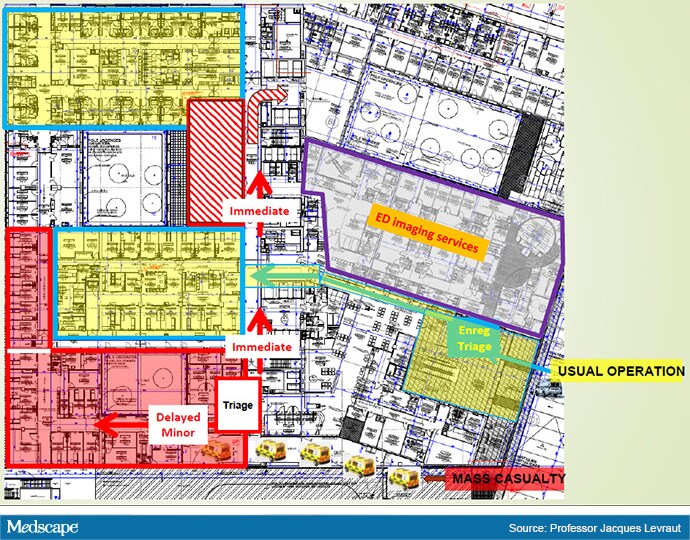

The second speaker, Levraut, began with an emphasis on preparation. "Since it is impossible to anticipate everything, we developed a white plan," he said as he flashed a patient flow map within the hospital (Figure). "The yellow zone," he pointed out, "is reserved for usual operation, then the red zone for the victims." They are distinctly two different pathways that can serve best the highest volume of victims but also ensure care for the usual hospital patient population.

Sample hospital patient flow.

He reiterated the importance of appropriate triage. "Stop the electronic medical file. Use paper." He described a color-coded identification system that includes approximate age, weight, and gender of the victim. It was spurred by a group of injured children who were too young to give accurate information. Other victims may be too impaired and still others will not survive to assist in their identification.

Stress-Induced Cardiac Effects

After the session, I asked Carli about the impact of the attacks in terms of cardiovascular stress on the medical staff, ancillary personnel, and even observers watching the events unfold on television. "What's remarkable is that during the attacks many providers and first responders don't eat, sleep, or have symptoms, but later, some have issues"." He mentioned the Israeli experience and pointed to studies on the physiologic effect of terror attacks on the general population.

One such study by Shenhar-Tsarfaty and colleagues[2] examined the negative impact of fear of terrorism (FOT) on resting heart rate and levels of inflammatory biomarkers. This is the area where most cardiologists will likely be called to service following a mass casualty incident.

An editorial in response had a fitting comment on the topic. "To the extent that millions of people are directly or indirectly exposed via the mass media to FOT, and that this exposure seems unlikely to wane in the foreseeable future, we can only speculate about a significant additional share to the global burden of CVD and mental disorders, including depression, inflicted by terrorism."[3]

During the question-and-answer session, as if on cue, there was a disconcerting boom from above followed by a continuous loud roar. I couldn't help but notice furrowed brows among those on stage. An audience member standing at the microphone said, half-joking, "This is not good." It turned out to be nothing, probably a mechanical incident with the HVAC, but the point of that uncomfortable moment was well taken.

The bottom line: no matter our specialty, we must be prepared for the real possibility that one day we may be called upon to serve in a mass casualty situation. It is our duty to be capable of helping others in all circumstances as best we can. For those terrible moments that we dread, but must anticipate, the cardiologist's stethoscope will need to take a backseat to other acute care tools. Perhaps tucking a few tourniquets in our office drawer and in the trunk of our car alongside gloves and gauze would be a good first step.

© 2019 WebMD, LLC

Any views expressed above are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the views of WebMD or Medscape.

Cite this: Melissa Walton-Shirley. Terrorism and Mass Casualty: All Specialties Should Prepare - Medscape - Sep 26, 2019.

Comments