At the American College of Cardiology meeting in New Orleans, I attended a talk titled, "Stop Smoking: Can South and Central America Take the Lead?" Uruguay already has.

A bus shelter in Montevideo, Uruguay, displays "Jeff the Diseased Lung." The ads and mascot were provided by John Oliver's Last Week Tonight show in support of Uruguay against Philip Morris.

When I walked into the session, I admit that I didn't even know whether Uruguay was located on the western or the eastern coast of South America. Daniel J. Pineiro, MD (who is from Argentina, no less) told the heartening tale of how one president's determination to save a nation started a revolutionary decline in Uruguay's tobacco use. Then his successor faced down Philip Morris, one of the largest and most powerful tobacco companies in the world. Even though I've been a staunch smoke-free advocate nearly all of my life, I'd never heard this story.

But first, a little about Uruguay. The country’s GDP is about $60 billion/annually with a population of 3.4 million (approximately 1% of the US population). That's remarkable, given that Philip Morris International has an annual revenue of $78 billion and a current work force of 80,600.

Here is where it gets even more interesting.

In 2003, president Jorge Batlle and the general assembly of Uruguay approved the World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO FCTC). The WHO FCTC is the first treaty negotiated under the auspices of the WHO. Its core measures include:

Price and tax measures to reduce the demand for tobacco.

Non-price measures to reduce the demand for tobacco, namely:

Protection from exposure to tobacco smoke;

Regulation of the contents of tobacco products;

Regulation of tobacco product disclosures;

Regulation of packaging and labeling of tobacco products;

Education, communication, training, and public awareness;

Reduction of tobacco advertising, promotion, and sponsorship; and

Measures to reduce tobacco dependence and cessation.

In 2006, Batlle's successor, president Tabaré Vázquez, who is also an oncologist, began to enact comprehensive smoking legislation. Uruguay became the first country in Latin America to prohibit smoking in enclosed public spaces. In 2008-2010, the smoke-free campaign "Libre de Humo de Tabaco" was gradually implemented by the Ministry of Public Health of Uruguay.

In response, Philip Morris International sued Uruguay. The company claimed that the antismoking policies violated a treaty between Uruguay and Switzerland, where Philip Morris International is based. There were two key measures that prompted the suit[1]:

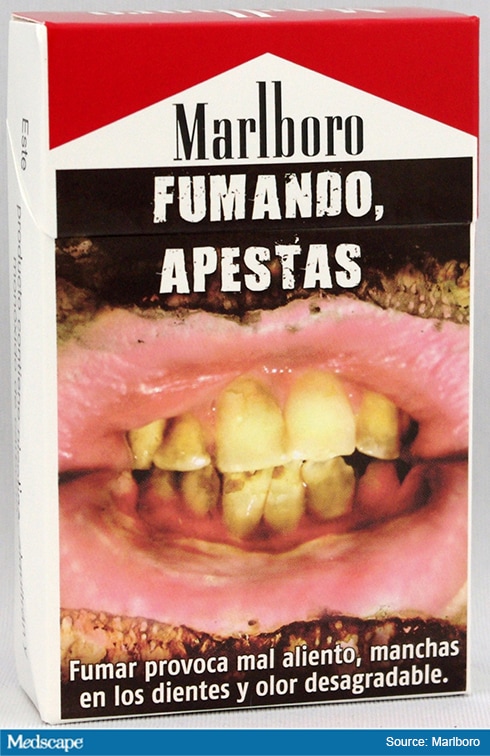

The law required that at least 80% of all cigarette packaging carry images warning about the health risks of smoking; and

Tobacco companies were barred from selling different versions of the same brand of cigarettes, effectively disallowing the sale of "light" cigarettes.

Example of cigarette plain packaging depicting the health risks of smoking.

The company tried to get around the legislation by simply varying the color of their packaging to suggest "lighter" versions of their product. Uruguay responded that because there were no proven health benefits to "light" versions, they would also be barred from offering different-colored packaging. This move was interpreted by Philip Morris International as a violation of their intellectual property rights, and they demanded compensation in the region of $25 million dollars. Silvina Echarte Acevedo, the legal adviser for the Uruguayan ministry of public health, told the Independent, "They are bullying us because we are small. This is like David and Goliath."

After a 6-year legal battle, on July 8, 2016, the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes ruled in favor of Uruguay. The case was thrown out, and Philip Morris was ordered to pay $7 million to Uruguay for legal costs. An astounding outcome.

As a result of the efforts and dedication of two presidents, a network of health advocates, and the framework set forth by their administrations, smoking rates in Uruguay fell from 39% to 30% in men and from 28% to 19% in women between 2006 and 2011. Youth smoking also declined.[2]

Pineiro presented a short video of President Vazquez who proudly and confidently proclaimed that "all countries who are implementing, or are preparing to implement similar policies could learn from this lesson." Apparently the United States is not yet one of them. The last slide of Pinero's presentation merely states, "Tabaré Vázquez, Hero de la salud [hero of health] 2018," because Vázquez was named the Pan American Health Organization/World Health Organization Public Health Hero of the Americas last year.

Now more than ever, our US White House could use a hero in the battle against tobacco addiction. The United States continues to spend $170 billion per year in direct medical care for tobacco-related illnesses,[3] as the tobacco industry spends $9 billion in advertising and marketing.[4] Couldn't we put all those billions of dollars together and do a lot of good instead?

Pineiro reminded us that the United States has not signed the WHO FCTC. Wouldn't one of the greatest legacies on behalf of any US president be to save the 480,000 citizens lost to tobacco use every year?[5]

Regain Our Lost Opportunity

In the Q&A after Pineiro's presentation, an audience member stepped to the microphone and asked, "Why can't we ban tobacco altogether?" The answer is that Big Tobacco has hidden tentacles in every pro-smoke town or can quickly embed them to gear up for a fight. They simultaneously court and intimidate politicians on local, state, and federal levels. They twist the "business owners' right to choose" into a political divide. They use scare tactics that "businesses will close" if you don't bathe your patrons in a cloud of smoke, a lie that has been debunked.[6,7]

The other issue is that we healthcare providers are too busy to pound the streets to collect signatures to impress our city councils, and we don't take the time to shout that tobacco-related death and dying are largely preventable. If we would just invest a few minutes a day to post the latest study on the harms of smoking on social media, or to speak at schools and talk to our local newspaper, think of the long-term impact.

It's time to call upon the United States to sign the WHO FCTC. It seems it would be pretty easy. Countries that did not sign the convention by June 29, 2004, may still do so by means of accession, which is a one-step process equivalent to ratification. It is deposited at the United Nations headquarters in New York, not too far from Trump tower.

If a small country such as Uruguay can accomplish so much with limited resources, we in the United States should hang our heads until we find a way to beat Big Tobacco on an even greater level. Let's hear it for tiny but mighty Uruguay. The world owes them a great debt of gratitude.

I would like to thank ACC's 7th Annual Conquering Health Challenges in the Emerging Worlds Symposium for shining a spotlight on this topic as well.

Follow Melissa Walton-Shirley on Twitter

Follow theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology on Twitter

Follow Medscape on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube

© 2019 WebMD, LLC

Any views expressed above are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the views of WebMD or Medscape.

Cite this: Philip Morris v Uruguay: A Story That Deserves Retelling - Medscape - Apr 18, 2019.

Comments