Jay H. Shubrook, DO: Hi. I'm Jay Shubrook, family physician and professor at Touro University California. We're here at the American Diabetes Association (ADA) 78th Scientific Sessions and continuing our discussions on diabetes guidelines around the world. Today I'm happy to have with me Dr Rucha Mehta, who is from the Apollo Hospital in Gujarat, India. Tell me a little bit about the guidelines in India for diabetes.

Rucha J. Mehta, MD: Thank you, Jay. It's great to be here. The guidelines in India are very similar to the ADA/European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) guidelines in terms of the targets for glycemic control. We have similar targets for diagnosis and treatment purposes: fasting plasma glucose ≥ 125, the 2-hour oral glucose tolerance test > 200, or a random plasma glucose > 200. When we treat, we also try to keep the [glucose] levels < 140-180, depending on the patient's tolerability.

The [ADA/EASD and Indian] guidelines are similar in terms of those treatment recommendations. Where we differ is in terms of the lifestyle changes. We all forget to look at the lifestyle changes. The Indian diet is largely—80%—a carbohydrate-based diet. When patients come to my clinic, we spend a lot of time focusing on lifestyle changes and trying to bring that down to 50% carbohydrates.

In the second step [following lifestyle], metformin certainly remains very popular. It has been around for a long time, so people are comfortable using it. For the majority of the primary care physicians (PCPs) who are taking care of patients with diabetes, we have not gotten away from the stepped approach. India is a huge country and we do not have enough endocrinologists and diabetologists to meet the needs, so we do rely heavily on PCPs.

Metformin, certainly, remains a drug of choice. In India, we also use a lot of alpha-glucosidase inhibitors. They seem to work very well to block the carbohydrate absorption and bring down postprandial glycemia. That is something we certainly do.

In addition, we have a lot of fixed drug combinations. You may have heard about some of the controversies going back and forth. Two- and three-drug combinations have become a part of our therapeutic drug use as well. Sulfonylureas are a mainstay of our treatments in spite of the hypoglycemia and the weight gain.

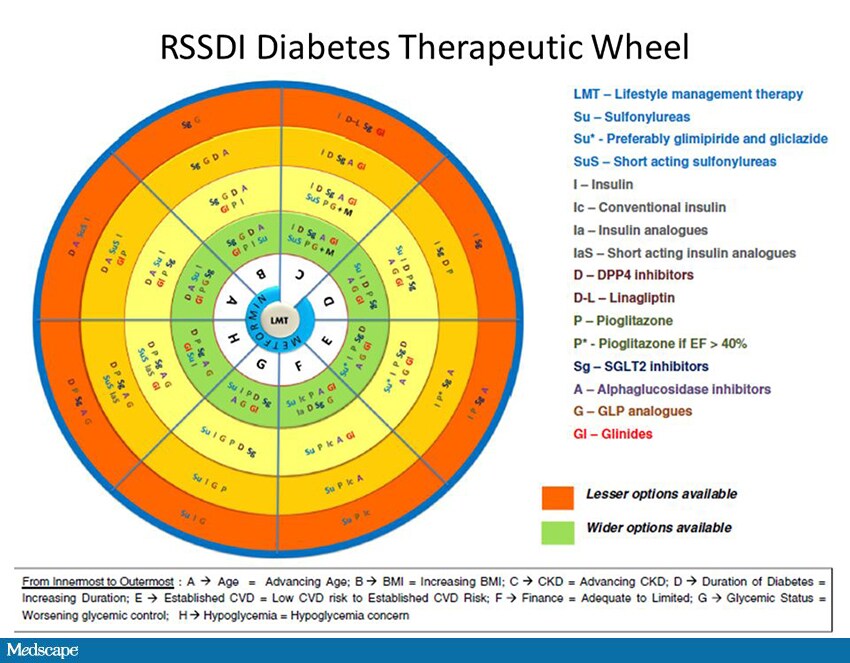

Just like the ADA, we have a society, the Research Society for the Study of Diabetes in India (RSSDI), which has a working committee that has come together and developed a guideline to help the PCPs.[1]

Shubrook: That's great. How is this guideline unique in terms of deciding treatments in type 2 diabetes?

Figure 1.

Mehta: I would like to focus on the RSSDI therapeutic wheel. At the center of the wheel is metformin. To make it simple for the PCP, we have [alphabetized the spokes of the wheel]. A is for age, B is for BMI, C is for complications, D is for duration of diabetes, [E is for risk of established cardiovascular disease], F is for financial status. Financial consideration becomes a big thing in a developing country like India. G is for glycemic control (the HbA1c), and H is risk for hypoglycemia.

For example, if an overweight or obese patient comes in to see you, the physician should look at the B spoke. If it's a BMI issue, [that spoke of the wheel indicates that] the first drug of choice after metformin will be a GLP-1 receptor agonist or an SGLT2 inhibitor, followed by all of the other classes.

If finance is a consideration, [the first recommendation is] metformin followed by alpha-glucosidase inhibitors and sulfonylureas. The more expensive medications would be far away from the center of the wheel. This really is more of a practical approach in a country like India, where we have a huge majority of patients who are very poor and unable to afford some of the medications.

In the county hospital, where I also go once a week, we see patients who do quite well if we spend some time with diet, metformin, alpha-glucosidase inhibitors, and sulfonylureas. This wheel is different and unique from what the other guidelines might have.

Shubrook: It sounds like it gives you very specific guidance based upon a specific patient factor.

Mehta: Yes, absolutely. If the patient has more than one combination, you can look at age and complications, and there is a unifying mechanism behind this also. It's not that we [only consider that] the patient is overweight, because he could also have a complication and [financial issues]. We do need to take a look at all of those together.

Shubrook: You talked about glycemic control. Do you have an A1c recommendation in your guidelines?

Mehta: The A1c recommendation is < 7%. Again, it's age dependent. With an older patient, we're happy keeping it between 7% and 8%, without causing hypoglycemia and any other risk for complications due to the medication use.

Shubrook: This is really interesting. It sounds like you do have guidance specific to the Indian population, which gives very specific guidance to the PCPs. There are patient-level factors that drive treatment, [which can be found on] the RSSDI therapeutic wheel.

Mehta: That's right. Thank you, Jay.

Shubrook: Thank you for coming today.

Medscape Family Medicine © 2018 WebMD, LLC

Any views expressed above are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the views of WebMD or Medscape.

Cite this: Focus on Lifestyle Changes: The Indian Diabetes Guidelines - Medscape - Sep 21, 2018.

Comments