Editor's Note:

Adam Gazzaley, MD, PhD, a neuroscientist at the University of California, San Francisco, grew up playing video games on his Atari console. Now as a successful researcher, he's exploring the potential role of video game-based therapy in slowing or preventing cognitive decline and possibly treating other brain conditions, including attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Medscape recently spoke with Dr Gazzaley about his research.

Medscape: How did you become interested in this idea of video games as therapy?

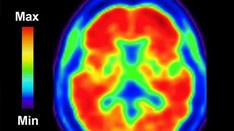

Dr Gazzaley: I guess it was around 8 years ago. We had been studying the neuromechanisms of attention and perception and working memory—especially in the context of aging and how interference, like distraction and multitasking, impairs performance in all people but especially older adults.

I became interested in the idea that we could use novel approaches to attempt to improve these declining cognitive abilities that we see with healthy aging. That was my initial goal. I reached out to friends of mine in the video game industry. Specifically, I reached out to LucasArts™, George Lucas's company, with a design for a game that I wanted to build. They were willing to help us develop it, which was a great asset.

The hypothesis I had was that if we challenged multitasking abilities in a video game that was a closed loop—meaning that it was constantly challenging players and continually advancing as players got better at it—we would see improvements in other cognitive skills that were not directly trained by the game but were related to multitasking through mechanistic features that we had been characterizing in the laboratory.

And so we did exactly that. We built this multitasking video game called NeuroRacer. We conducted numerous studies on it over the years and eventually published in Nature in 2013.[1]

We found that older adults indeed improved their ability to multitask on the game and actually did so to a really remarkable degree, even exceeding levels of a 20-year-old on a single game play. We also confirmed the hypothesis by revealing evidence that other tasks, such as holding the memory of faces in mind for short periods of time, as well as vigilance—a standard attention task—also improved significantly in our older adults. This was seen only in the group that played the multitasking version of NeuroRacer, not the group that played a single-task version, which was our active control group. This revealed to us that the active ingredient in the game was this multitasking challenge, as we hypothesized, that was leading to the benefits.

Medscape: How does NeuroRacer contrast with all of the various brain fitness programs released in recent years?

Dr Gazzaley: Every game is different, just like every drug is different. They all have unique active ingredients and different degrees of efficacy in different populations. And that's how we view games. There will probably prove to be many different ways of formulating and delivering it to different populations that have distinct deficits.

However, compared with many existing products used in cognitive training research, we focus on very high-level game development in the laboratory. We use closed-loop algorithms and very rapid updating of the challenge of the game, as well as a rapid feedback in gameplay. And then we validate at a high level as well, bringing on the most rigorous level of methodology and aiming for randomized control trials that are double-blinded and placebo-controlled.

Medscape Neurology © 2016 WebMD, LLC

Any views expressed above are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the views of WebMD or Medscape.

Cite this: Beeps, Blips, and a New Class of Medicine: Video Games - Medscape - Apr 22, 2016.

Comments